Kashmir Shawls: Issues in Style and Chronology

From HALI: The India Edition: An unusual sale devoted to one tradition was held at Christie’s London from 11-18 June 2019. Exclusively online, it featured Kashmir shawls gathered together by one man—the collector extraordinaire Samuel Josefowitz (d. 2015), best known for his early championing and collecting of the Pont-Aven School, centred upon Paul Gauguin. Jeffrey B. Spurr reviews some key lots.

The sale garnered some pretty spectacular prices (see HALI 201, pp.137-8). It featured numerous beautiful, interesting, and uncommon pieces alongside less impressive ones, with 71 out of 85 lots sold. Nearly all were Kashmiri, though some were panels constructed in Persian bazaars of jamawar (shawl cloth), the lone exceptions being two Jacquard woven shawls, one a French ‘pivot’ long shawl, the other a moon shawl not identified as definitively French. Twelve were long shawls, palledar, featuring classic pallus (end panels), mainly woven before 1830; six were palledar fragments, including individual pallus; two were late palledar-format dorukha (two-sided) long shawls, another a dorukha shawl of an overall design with the simplest of end finishes. Eight were European-market long shawls, plus one rare long shawl featuring Devanagri script.

But the principal focus of Josefowitz’s collecting appears to have been moon shawls (chandar): two in the earlier, smaller format employed in the east as headscarves, and 26 in the larger format, an early 19th-century innovation, often exported and worn as wraps, plus the French copy moon shawl. Other square (rumal) shawls were principally woven for export to Europe and America, characterised by the European market style. Twelve were kani-woven (double-interlocked twill tapestry), while six were embroidered. Four of the latter represented a well-known pictorial type whose markets were probably Eastern as well as Western. Finally, the sale featured four jamawar lengths or fragments, plus three Perso-Kashmiri prayer mats (two in one lot), fashioned from combinations of shawl cloth, and one controversial panel. I will not mention or discuss all these shawls, and this review will focus principally on the moon, long, palledar and European market shawls. By discussing some of them in relation to each other, I hope to provide a coherent view.

Regarding issues of chronology, sometimes being off by ten years can matter in dating a shawl, given that significant changes occurred continuously from the very late 18th century through the first decades of the 19th. My understanding of dating is derived from the presence of Kashmir shawls in European paintings (mostly portraits), as well as Mughal and Deccani miniatures, and Safavid, Afsharid, Zand and Qajar murals and oil paintings, where sitters are often known, and clear chronologies have been established.

Concerning nomenclature, it makes no sense to refer to the European market long shawls as doshalla, which strictly speaking means ‘two shawls’, and refers to two historical facts: First, when shawls were refined but simple undyed lengths, Emperor Akbar initiated the convention of wearing two shawls dyed in contrasting colours, an innovation described by his court chronicler Abu’l Fazl. Later, after kani (double-interlocking twill tapestry) weaving was introduced as a means of decorating shawls under Emperor Jahangir, the term continued in use, referring to the habit of weaving pairs of shawls in the same design. This Indian term loses its purchase for shawls exported to Europe—even if the convention of weaving them in pairs continued. Given the practice in Srinagar of reciting directions for each pick, all looms within hearing could weave the same design.

Palledar shawls

Palledar shawls are the classic form in this tradition, basically two end panels (pallu) and an open field (later sometimes decorated in more expensive shawls), featuring hashiyas (side borders) and zanjirs (transverse borders). These were principally worn as shoulder wraps. With one possible exception, none of the longer and narrower sashes or turban cloths were collected by Mr Josefowitz.

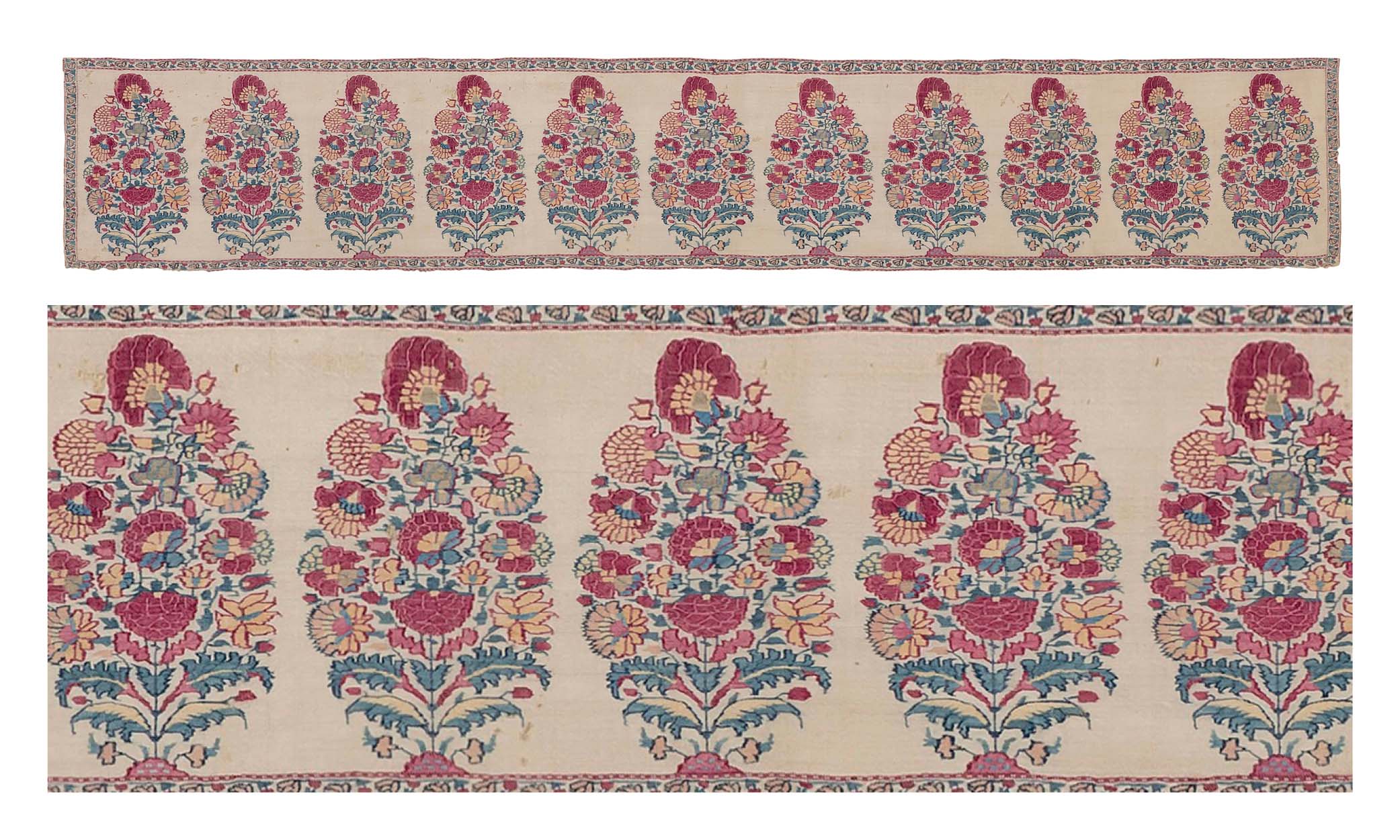

Kashmir long shawl pallu fragment, 17th century. Christie’s, online sale, 11-18 June 2019, lot 19. Estimate £4,000-6,000, sold for £56,250

Lot 19 was a truly splendid and complete pallu or end panel, given an enthusiastically early date. Arguably the most beautiful textile in the sale, the butas were carefully conceived, finely drawn and coloured. These floral elements represent a relatively early stage in the shift from the ‘bush’ form of buta to the ‘modern’ buta or ‘paisley’ motif of the 19th century, with a progressively more defined profile, as well as an early stage in the emergence of the ‘millefleurs’ mode within the buta itself, featuring several different types of flowers rather than one. Still, it is not 17th century, but dates to around 1700-1730.

Kashmir long shawl, circa 1750-1760. Christie’s, online sale, 11-18 June 2019, lot 13. Estimate £4,000-6,000, sold for £35,000

Lot 13, a fine, complete palledar shawl with a rare deep indigo ground (see HALI 201, p.137), deserves more extended discussion. But for the blue ground, it is nearly identical to the shawl in Sir Joshua Reynolds’ famous portrait, Mrs Baldwin in Eastern Dress (ca. 1782), at Compton Verney. How long had it been in existence before Mrs Baldwin placed it next to her for her portrait? Impossible to know for certain, and it was not so much an expression of the up-to-the moment style (as it might have been in a portrait from a later date), as another orientalist gesture in accordance with the garb she had adopted for the portrait, reflecting her own experience of the East. I date the little butis found in three rows in the pallus to about 1750-1760, not ‘circa 1700’.

Kashmir long shawl fragment, circa 1810. Christie’s, online sale, 11-18 June 2019, lot 68. Estimate £3,000-4,000, sold for £3,750

Another very refined long shawl, lot 68 was truncated in length and width, the better portion of the original hashiyas (with their zig-zag vines) surviving. The simplicity of the upper field additions in the pallus would suggest 1810 at the latest, but the highly unusual though only partially surviving sprigs in two corners of the field, indicate a slightly later date. Every tiny buti in the field sports a stem inclined to the side, an almost universal feature in such motifs. These soberly coloured shawls dominated by the colour blue ultimately inspired the Jacquard ‘kirking shawls’ of Scotland.

Kashmir long shawl, circa 1815. Christie’s, online sale, 11-18 June 2019, lot 3. Estimate £6,000-8,000, sold for £22,500

Lot 3 had design features, including its gorgeous hashiyas and zanjirs with their complexly conceived vine scrolls sporting a single type of bloom, that we do not see till around 1815, though the complications in the pallu design may have emerged a couple years earlier. No pallu woven in 1800 (as dated by Christie’s), had anything but simple butas in its end panels, and the rows of butis in the field of this rich and expensive shawl were not as yet facing in alternate directions, as they are here.

Lot 37 was an austere but very refined shawl, probably woven for a Sufi shaykh or other very senior man, its simplicity comporting with his dignity. I have discussed the character of the inner border around the field, a sort of diminished daur (the field decoration on long shawls along its sides emerging close to 1820), in the context of lot 68, which inclines me to date it somewhat earlier than ‘circa 1820’, as indicated in the catalogue.

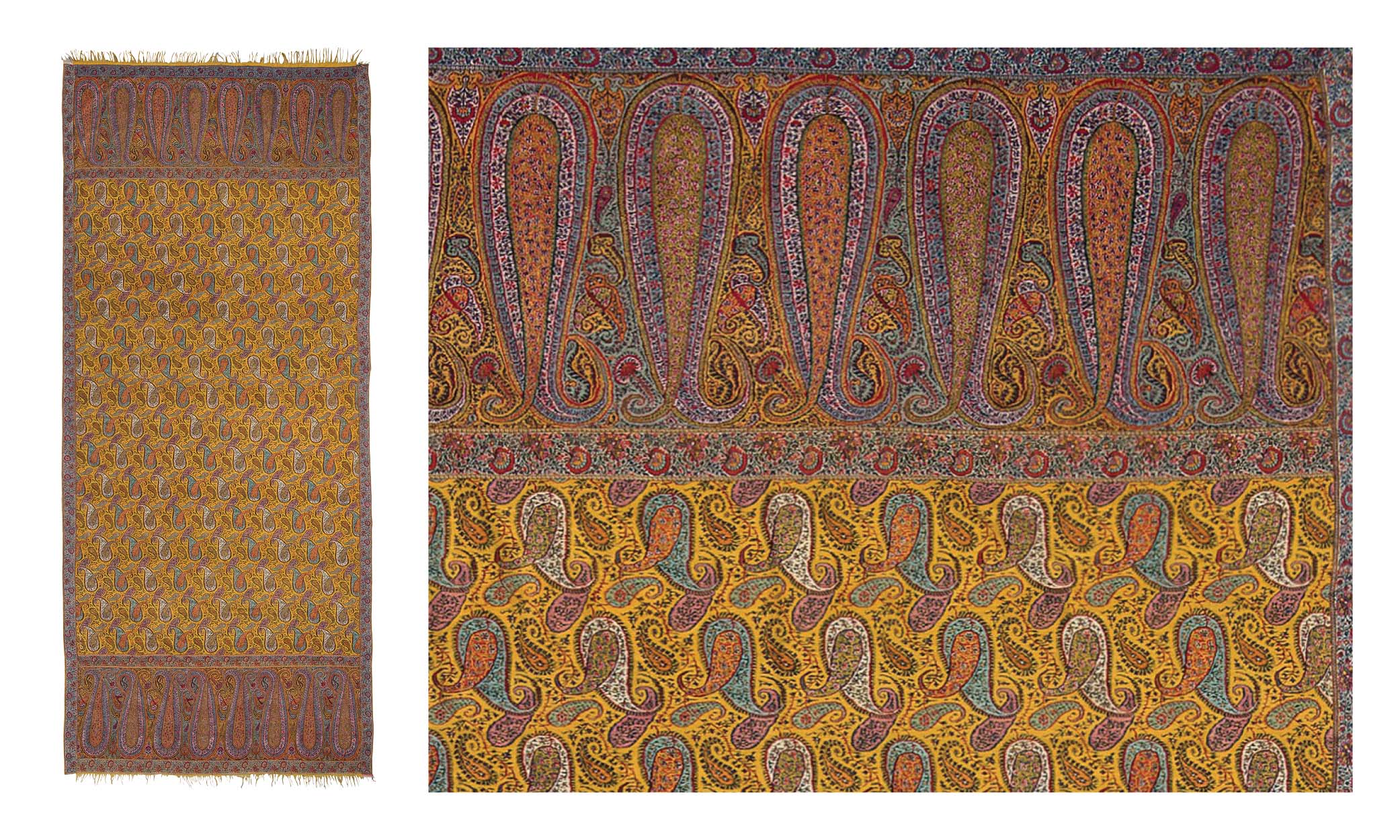

Kashmir long shawl, circa 1820s. Christie’s, online sale, 11-18 June 2019, lot 70. Estimate £2,500-3,500, sold for £10,000

Lot 70 was the first of three long, palledar shawls that one might call ‘high concept’, due to their strong and novel palettes that must have attracted Mr Josefowitz. They provide a vivid contrast to lot 37. Here, white, yellow ochre and blue-green ground colours are employed to unify the whole shawl, from pallus through the daur to the strong, khat-rast (striped) field, with its sharply drawn flower-laden scrolling vines in the wider stripes. Despite this shawl’s striking appearance, given the essential reserve of the very formally drawn, albeit densely embedded pallu butas, and the conservative, relatively narrow hashiyas, I would date it to the 1820s.

Kashmir long shawl, circa 1830-1835. Christie’s, online sale, 11-18 June 2019, lot 42. Estimate £5,000-7,000, sold for £16,250

Lot 42 is a remarkable palledar shawl as it features a very strong and most unusual palette, and a highly articulated field design against a yellow ochre ground. It was woven just as the interplay of crosscutting and overlapping butas and butis was developing, here clearly manifest in pallus and field, which would continue in ever more complex, even riotous form, in the European market shawl. It probably dates to 1830-1835, not ‘mid-19th century’. Like lot 42, but even more so, lot 64 features a highly unusual, almost garish, palette for a palledar shawl, and distinctive design ideas. Its long butas remain classic examples of the sort with refined internal articulation that emerge in the 1820s. This characteristic is echoed here in the daur and kunj (corner) butas. However, the pallu field is now broken up almost arbitrarily into segments with different field colours. A pervasive design idea in the shawl is a white outlining of the pallu butas, all elements in the daur, and around the kunj butas. This concept is repeated in a more simplified form in red of the ‘vine’ around each little buti in the very dense field, where another order of design is created by using different field colours in adjacent polylobed sections juxtaposed across the field in yellow, orange, pink and blue. There is nothing else like it, and it probably dates to the later 1830s.

European market long shawls

A critical design shift emerged in the early 1830s, responding to changes in European fashion, and developments in the Jacquard loom whose practitioners produced shawls challenging to Kashmiri designers, resulting in a transformative change in design more dramatic than the slow evolution of earlier periods in the long shawl, accompanied by the emergence of the rumal (square shawl), distinct from though conforming to the expansion in the size of moon shawl, which directly preceded it, and which probably formed a sort of model for the form. The result was the European market style. In the earlier shawls in this new style, we can still usefully refer to pallu, daur, hashiya and zanjir, though these terms make ever less sense as designs develop over the following decades.

Despite missing the extended butas of its end panels, lot 40 was an early European market long shawl on the basis of the design of its daur with its strongly overlapping bent-tipped butas, and the highly novel extensions from the daur: two types of projections into the field, one rounded, one polyfoliate, bouquets and little peacocks between them, plus the red colour of its field, highly favoured in Europe. It probably dates to the early-mid 1830s, and is thus a contemporary of lot 42, this latter shawl still destined for the local, Eastern market as much as for export to Europe. The long, open field of lot 40 is indicative of its early date for a European market shawl.

Kashmir long shawl, before 1840. Christie’s, online sale, 11-18 June 2019, lot 2. Estimate £2,000-3,000, sold for £6,000

The riotous form of design complication concerning butas mentioned in lot 42, prefigured lot 40, reaches an advanced stage in lot 2 even though the principal butas remain confined within the original end panels, from which they would soon be liberated (lot 4). The detail is fantastic, even managing to hide little peacocks within the bodies of the large butas. As with lot 40, we encounter novel projections into the long field from what would have been the original daur in lot 2. These appear to comprise trays supporting fantastic vases alternating with equally fanciful pavilions, all resting on boats. With its long field, 1840 would be the latest one would date it. This shawl also features end fringes comprising short lengths of monochrome pashmina sewn one to the next, the earliest manifestation of a consistent feature of European market shawls.

Kashmir long shawl, circa 1845. Christie’s, online sale, 11-18 June 2019, lot 25. Estimate £3,000-5,000, sold for £21,250

Lot 25 was a brilliant and unusual European market shawl, suffering only from minor design flaws. The presence of wonderfully designed peacocks is by no means unprecedented, but none that I know integrate this concept across the zanjirs, the pallus, and the daur. However, to serve the imperative of getting the grand peacocks in the end panels to work completely (with only an odd emergent tail at the left), a certain amount of design inconsistency is to be observed in the four zanjirs, whose confronting pairs of peacocks do not work all of the way across. The main problem is in the daur, where the designer and his weavers simply could not get the square panels with their individual peacocks, cross-cutting butas and yellow ground tendrils to work all the way across in any direction, with some rather awkward consequences. Despite those problems, the shawl features the most elegant and refined projections into the field from the daur. They are designed as if they emerge from the daur, but do not and must have been woven separately but with the greatest care, a superb achievement in kani weaving given how exposed these designs are. Dating to 1845 is correct, but no later since the somewhat ghostly butas remain confined to the end panels.

Moon shawls (chandar)

No fewer than 28 moon shawls make what is relatively scarce seem common. The brief catalogue essay that defines moon shawls claims that the moon shawl ‘first appeared in Kashmir in 1680’ and was inspired by ‘sixteenth century Cairene carpets produced in Ottoman Egypt”. Neither statement is true. There is no evidence for the existence of moon shawls in their original, small format, made for the local market as headscarves, before the mid-18th century. The notion that because some Cairene Ottoman carpets had round floral medallions, and a couple exist appearing singly with corner quarter medallions, they necessarily represented the design origin for moon shawls is sheer fantasy. The market for Cairene carpets was not Srinagar but, largely, Europe. Independent invention has occurred time and again in textile history. Moon shawls were originally Indian in conception and use. The essay also asserts: ‘moon shawls were largely produced according to Western stylistic demands and became particularly favoured by British and French ladies in the last quarter of the eighteenth century’. Utterly false. Shawls straggled into Europe during the second half of the 18th century, but only became a serious vogue about 1804 after Empress Josephine had herself painted wearing two of them. That Thomas Gainsborough painted Mrs Hingeston about 1787 wrapped in what has been identified as a moon shawl despite depicting neither moon nor quarter moon (one sees little butis like those in lot 31, plus a glimpse of hashiya), is not evidence of significant European demand, let alone influence, in that period. Evidence must wait to be exhibited in the dramatic expansion in size of moon shawls in the early 19th century, which was a response to new European markets in need of adequate wraps.

Kashmir moon shawl, late 18th century. Christie’s, online sale, 11-18 June 2019, lot 31. Estimate £6,000-8,000, sold for £20,000

The sale included two rare, early moon shawls of the original type, employed as head scarves from the mid-18th century into the early 19th century, and representing the two major types: lot 31, with spot motifs of little butis ranging across the field in offset rows (see HALI 201, p.138), and with simple stripes containing florettes in jamawar mode in lot 75, inexplicably dated to 1850 in the catalogue, though both date from the latter decades of the 18th century. The red and white stripes of lot 75 represent the earliest form of this khat-rast mode, ubiquitous in yardage produced during these decades and into the 19th century. Both shawls display the most common type of hashiyas and zanjirs of the later 18th and early 19th centuries—a scrolling vine exhibiting four different flower heads, two red, a yellow, and a blue (variants exist).

Kashmir moon shawl, circa 1815. Christie’s, online sale, 11-18 June 2019, lot 6. Estimate £6,000-8,000, sold for £6,875

Lots 5 and 6, which reveal what may be described compositionally as the transition from the moon shawl as headscarf to the larger moon shawl as wrap by extending the former with broad pallu-like borders—here really ‘borders’! The slightly earlier of the two is lot 6, which features a most unusual field of round and ogival floral medallions in alternate rows. These are connected laterally by short elements akin to hashiyas that create diamond forms and contribute to the impression of a lattice, with projecting, pendant mini palmettes from top and bottom of each ‘diamond’, the whole overlying a vast field of interconnected flowers. The large border butas reveal an early version of the articulated centre and are so richly conceived that only the simplest field elements are included. The moons are of a conventional early type but are inflected by the addition of little jars and trays below the four secondary blossoms in their fields. The corners of the broad borders are very nicely conceived, demonstrating how thoroughly the design had been worked out. As the catalogue indicates, it probably dates to circa 1815.

Lot 5 is one of a small number of related, highly superior moon shawls that must have been woven in the same workshop, though it is unique among them by virtue of its broad, pallu-like borders. The design integration is very successful, with smaller, very stately butas in rows across the field reflecting the same composition as those in the borders, which are unique in their drawing, and in sharp contrast with the large feathery butas in the moons. The articulated interiors of the latter indicate a date about 1820-1825, not ‘second quarter 19th century’. As with Lot 6, care was taken in designing the border corners, and the richly conceived butas seem to have demanded a return to minimal field embellishment as well.

Kashmir moon shawl, circa 1855-1860. Christie’s, online sale, 11-18 June 2019, lot 4. Estimate £2,500-3,500, sold for £10,625

What to make of lot 4? Its dramatic and unusual design is a sort of hybrid between the moon shawl and the standard European market rumal shawl, though it is a stellate design (with 16 points) rather than a moon at all in spite of the clear formal relationship between the concepts. Also, like standard moon shawls, it is all field and border. Its central star really is sui generis, a unique device, with other, complexly embedded star forms embellishing its interior. It was probably woven around 1855-1860 given that its attached embroidered fringes are still only to be found on two sides in the earlier European market manner. Whether placed here or with European market square shawls, it is a thing unto itself.

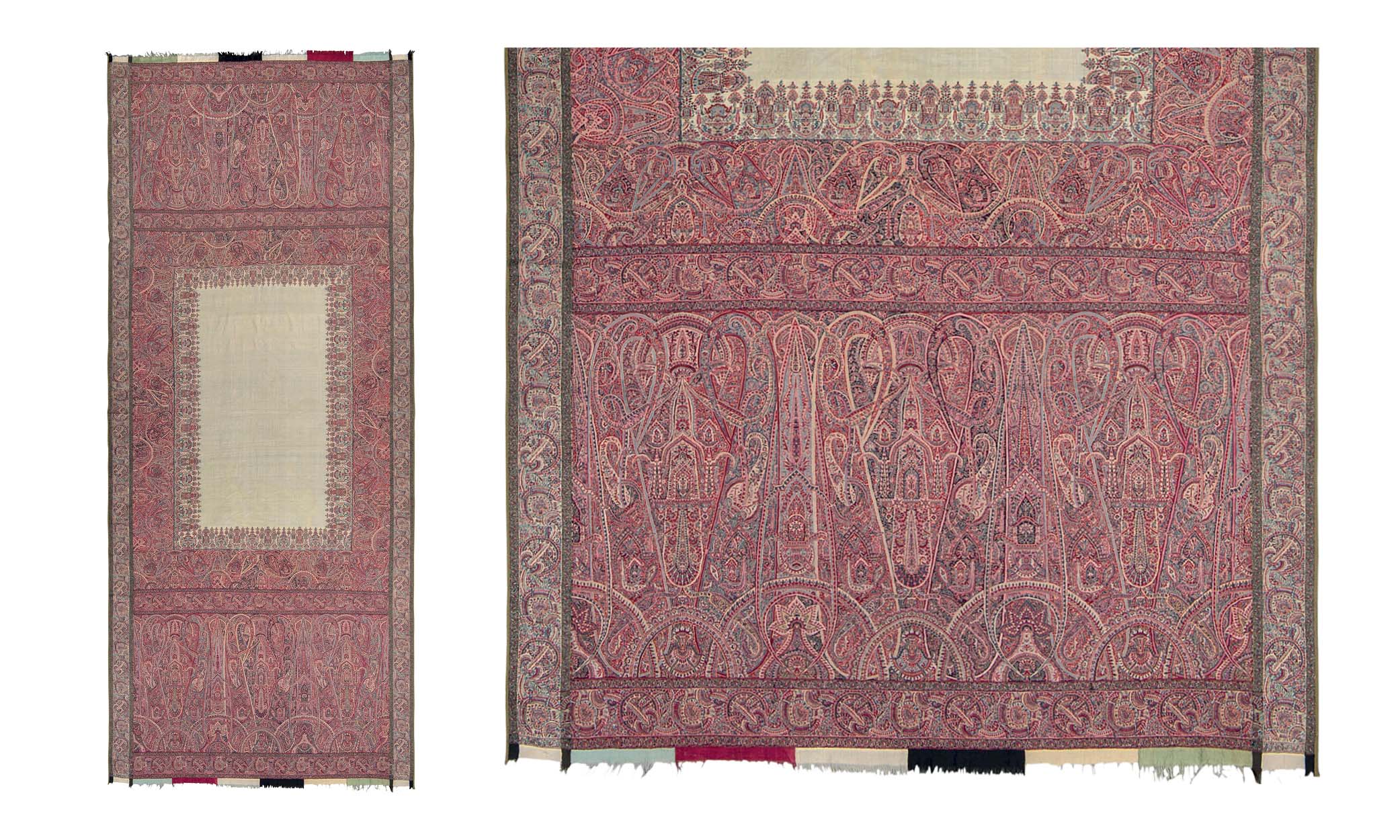

Rumal (square) European market shawls

Kashmir square shawl, circa 1840. Christie’s, online sale, 11-18 June 2019, lot 32. Estimate £3,000-5,000, sold for £22,500

Lot 32 is a brilliantly successful European market shawl. It has retained the concept of the daur, lopping off the palus. The leaning, long tipped butas of the daur are only a step beyond those in the long shawl in lot 40. What makes it wonderful is the successful conception of the centre, with elegant, even longer tipped butas emerging from the corners of the field, integrated with the flared tails of paired peacocks on each side. It dates to about 1840, based upon how well-conceived it is and the character of its borders.

Kashmir square shawl, circa 1840-1845. Christie’s, online sale, 11-18 June 2019, lot 8. Estimate £2,500-3,500, sold for £3,000

A square shawl, lot 8, features wonderfully controlled drawing, especially in its centre with its small, five-clawed dragons, and dates to around 1840-1845, not 1860. The designer was figuring out the transition from the concept of the long shawl to the rumal shawl here as well, but here with a greater challenge than in the case of lots 32 and 38, for he employed the conceptual arrangement of the pallus, with their elongated butas, extended to all four sides, not the daur, an inherently greater design problem, resulting in reasonably successful corner solutions though flanked by rather awkward truncated butas, joined together.

Jamawar

Kashmir assembled textile, circa 1805-1810. Christie’s, online sale, 11-18 June 2019, lot 17. Estimate £5,000-7,000, sold for £150,000

The ‘mat’ in lot 17 is a challenging textile to construe from images. It was woven at the apogee of the ‘millefleurs’ mode and can be dated to about 1805-1810; definitely not mid-18th century. The question: how was this constructed since it is not a continuously woven textile as are the known panels in niche format that were most likely used as niche curtains, including one at the MFA, Boston (no.99.156). First, the would-be zanjirs are, in fact, hashiyas that have been sewn on the lateral sides. Hashiyas are readily detectable because of the disciplined character of their very narrow guard stripes compared with the looser appearance of those bordering zanjirs. In this case, the zanjirs are where the hashiyas should be if woven in—as in the MFA example—and vice-versa. The rather striking main border appears to be four lengths of the same woven jamawar material sewn on, the lateral lengths extending from top to bottom, the transverse ones narrower. The inner border also features a continuous design, but it was not woven in as we see it here, and features two different warp colours, white and blue, inconsistently applied around the field. The central feature (field) appears at first blush to be a refugee from a moon shawl, including the corner quarter moons; however, I am hard-pressed to detect the seams, despite the inconsistencies in the design, such as two red flower heads above three of them absent any other balancing feature. All of these parts could have been woven at the same time, but they were not woven as a continuous textile object even if woven to be part of the same object and are awkwardly put together.

A note regarding pictorial embroidered (amli) rumal shawls: Mr Josefowitz clearly appreciated animated shawls, as the unprecedented number of very fine kani shawls featuring peacocks indicates. No fewer than four embroidered rumal shawls were on offer, probably dating to around the third quarter of the 19th century. That appears to have been three too many, since only lot 55, a topographical embroidery sold. It displays an unmatched abundance of scenes and figures, and an endless parade of animals running in great loops across the field to provide visual coherence. It is very likely best of type.

Kashmir embroidered square shawl, third quarter 19th century. Christie’s, online sale, 11-18 June 2019, lot 55. Estimate £7,000-10,000, sold for £32,500

An abridged version of this article appeared in HALI 203, Spring 2020.