Photo Album: India, February 2018

Textiles of India: Courtly & private collections of North West India

162 images

Highlights from the first HALI Tour to India—Delhi, Jodhpur, Jaipur, Ahmedabad, Champaner, Surat, Mumbai—3-16 February 2018

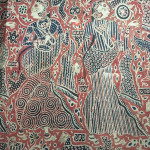

- Temple hanging (detail), embroidery and appliqué, Karnataka or Tamil Nadu, south India, 1750-1800, Ramā-Abhiramā: The Beauty of Ramā in Indian Art and Tradition’, National Museum, Delhi

- Temple hanging (detail), embroidery and appliqué, Karnataka or Tamil Nadu, south India, 1750-1800, Ramā-Abhiramā: The Beauty of Ramā in Indian Art and Tradition’, National Museum, Delhi

- Temple hanging (detail), embroidery and appliqué, Karnataka or Tamil Nadu, south India, 1750-1800, Ramā-Abhiramā: The Beauty of Ramā in Indian Art and Tradition’, National Museum, Delhi

- Painting, Bikaner, Rajasthan, 16th century, ‘Ramā-Abhiramā: The Beauty of Ramā in Indian Art and Tradition’, National Museum, Delhi

- Painting, Jaipur, Rajasthan, 17th century, ‘Ramā-Abhiramā: The Beauty of Ramā in Indian Art and Tradition’, National Museum, Delhi

- Embroidered costume, Meghalaya, National Museum, Delhi

- Carved window frame, Gujarat, 18th century, National Museum, Delhi

- Mandapa of Jain temple, Gujarat, 17th century, National Museum, Delhi

- Sheesh Gumbad, Lodi Gardens, circa 1490s, Delhi

- Sheesh Gumbad, Lodi Gardens, circa 1490s, Delhi

- Mosque, Lodi Gardens, circa 1490s, Delhi

- Mosque, Lodi Gardens, circa 1490s, Delhi

- Tomb, Lodi Gardens, circa 1490s, Delhi

- Ceramic horse, Sanskriti Foundation, Delhi

- Terracotta Museum, Sanskriti Foundation, Delhi

- Bihar murals, Terracotta Museum, Sanskriti Foundation, Delhi

- Bihar murals, Terracotta Museum, Sanskriti Foundation, Delhi

- Textile Museum, Sanskriti Foundation, Delhi

- Textile Museum, Sanskriti Foundation, Delhi

- Ikat on the loom, Textile Museum, Sanskriti Foundation, Delhi

- Kantha, Textile Museum, Sanskriti Foundation, Delhi

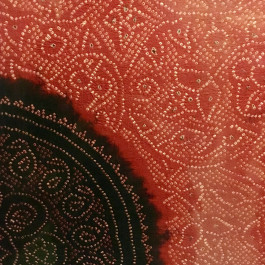

- Odhani Bandhani, Kutch, Textile Museum, Sanskriti Foundation, Delhi

- Sanskriti Foundation Founder, O.P. Jain (right) and curator Jyotindra Jain, Delhi

- Leika Poddar patron of the Devi Art Foundation at ‘A Search in Five Directions: Textiles from the Vishwakarma Exhibitions’, National Handicrafts and Handloom Museum, Delhi

- ‘A Search in Five Directions: Textiles from the Vishwakarma Exhibitions’, National Handicrafts and Handloom Museum, Delhi

- Nagabandha ikat sari, Orissa, 1981 ‘A Search in Five Directions: Textiles from the Vishwakarma Exhibitions’, National Handicrafts and Handloom Museum, Delhi

- Patola panel, Gujarat, 1986 (foreground), ‘A Search in Five Directions: Textiles from the Vishwakarma Exhibitions’, National Handicrafts and Handloom Museum, Delhi

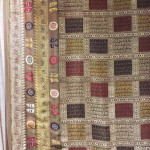

- Charbagh chanderi panel, Madhya Pradesh, 1981, ‘A Search in Five Directions: Textiles from the Vishwakarma Exhibitions’, National Handicrafts and Handloom Museum, Delhi

- Kodalikarrupur sari, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, 1981/1986, ‘A Search in Five Directions: Textiles from the Vishwakarma Exhibitions’, National Handicrafts and Handloom Museum, Delhi

- Kantha, National Handicrafts and Handloom Museum, Delhi

- Mehrangarh Fort from The Raas Hotel, Jodhpur

- Heritage buildings, The Raas Hotel, Jodhpur

- Stepwell, Jodhpur

- Mehrangarh Fort from The Raas Hotel, Jodhpur

- Jodhpur from Mehrangarh Fort

- Jodhpur from Mehrangarh Fort

- Elephant howdah presented to Maharaja Jaswant Singh (1639-78) by Emperor Shah Jahan in 1657, Mehrangarh Fort, Jodhpur

- Bamboo screen (chic), 18th century, Mehrangarh Fort, Jodhpur

- Maharaja Ram Singh celebrating Diwali, painting, Shihab-ud-din, circa 1750, Mehrangarh Fort, Jodhpur

- Tent hangings, Mehrangarh Fort, Jodhpur

- Woven hanging, 18th-19th century, Mehrangarh Fort, Jodhpur

- Mirrored meditation chamber, Mehrangarh Fort, Jodhpur

- Textile stores, Mehrangarh Fort, Jodhpur

- Embroidered coat, textile stores, Mehrangarh Fort, Jodhpur

- Embroidered coats, textile stores, Mehrangarh Fort, Jodhpur

- Dinner at Mehrangarh Fort, Jodhpur

- Roopraj the dhurrie weaver

- Turban demo by Roopraj

- Dhurrie on the loom by Roopraj

- Roopraj the dhurrie weaver

- Roopraj the dhurrie weaver

- HALI Tour group with Roopraj the dhurrie weaver

- A hoard Hissar shawls at a patchwork factory

- Tie-dye home workshop, Jodhpur

- Tie-dye home workshop, Jodhpur

- Jodhpur train station

- Silver & Art Palace, Jaipur

- Silver & Art Palace, Jaipur

- Mochiwork embroidery, Silver & Art Palace, Jaipur

- Kashmir shawl, Silver & Art Palace, Jaipur

- Kantha, Silver & Art Palace, Jaipur

- Mochiwork embroidered skirt, Silver & Art Palace, Jaipur

- Village women in tie-dyed headscarves arriving into Jaipur for a mela

- Jantar Mantar 18th century observatory (UNESCO World Heritage site), Jaipur

- Jantar Mantar 18th century observatory (UNESCO World Heritage site), Jaipur

- Jantar Mantar 18th century observatory (UNESCO World Heritage site), Jaipur

- Rugs from the stores on the roof top at the City Palace, Jaipur

- Rugs returning to the stores, City Palace, Jaipur

- Indian pile carpets, 17th century, Albert Hall Museum, Jaipur

- Indian pile carpets, 17th century, Albert Hall Museum, Jaipur

- Indian pile carpets (little seen), 17th century, Albert Hall Museum, Jaipur

- Indian pile carpets with 17th century label, Albert Hall Museum, Jaipur

- Indian pile carpet, 17th century, Albert Hall Museum, Jaipur

- Indian pile carpets, 17th century, Albert Hall Museum, Jaipur

- Indian pile carpet, 17th century, Albert Hall Museum, Jaipur

- ‘The Jaipur Garden Carpet’, Safavid chaharbagh carpet, Kerman, south Persia, late 16th or early 17th century, Albert Hall Museum, Jaipur

- Rajasthan Fabrics & Arts, textile gallery, Jaipur

- Rajasthan Fabrics & Arts, Jaipur

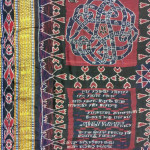

- Bandhani Odhani (tie-dye headscarf), Rajasthan Fabrics & Arts, Jaipur

- Naga Brahman’s patola (double ikat), textile gallery, Jaipur

- Woven cloth with metal thread, Rajasthan Fabrics & Arts, Jaipur

- Mashru, Rajasthan Fabrics & Arts, Jaipur

- Resist dyed fabric with applied gold details, Rajasthan Fabrics & Arts, Jaipur

- Rajasthan Fabrics & Arts, Jaipur

- Tent hangings, Rajasthan Fabrics & Arts, Jaipur

- Amber (Amer) Fort, Jaipur

- Amber (Amer) Fort, Jaipur

- Amber (Amer) Fort, Jaipur

- Amber (Amer) Fort, Jaipur

- Amber (Amer) Fort, Jaipur

- Hoops for hanging textile drapes and awnings, Amber (Amer) Fort, Jaipur

- Amber (Amer) Fort, Jaipur

- Iris flowers carved in marble, Amber (Amer) Fort, Jaipur

- Amber (Amer) Fort, Jaipur

- Amber (Amer) Fort, Jaipur

- Amber (Amer) Fort, Jaipur

- Amber (Amer) Fort, Jaipur

- Amber (Amer) Fort, Jaipur

- Amber (Amer) Fort, Jaipur

- Anokhi Museum of blockprinting, Jaipur

- Brigitte Singh, block printer, Jaipur

- Rosemary Crill with Brigitte Singh, Jaipur

- Brigitte Singh’s atelier, Jaipur

- Block printed fabric by Brigitte Singh, Jaipur

- Block print designs by Brigitte Singh, Jaipur

- Carving printing blocks at Brigitte Singh’s atelier, Jaipur

- Carved printing blocks at Brigitte Singh’s atelier, Jaipur

- Carving printing blocks at Brigitte Singh’s atelier, Jaipur

- The HALI Tour group at Brigitte Singh’s atelier, Jaipur

- Caravanserai sleeping platforms at the stepwell, Ahmedabad

- Caravanserai stepwell, Ahmedabad

- Local guide Nirav Panchal, caravanserai stepwell, Ahmedabad

- Caravanserai stepwell, Ahmedabad

- Caravanserai stepwell, Ahmedabad

- Amit Ambalal’s first pichawai acquisition, private collection, Ahmedabad

- Amit Ambalal’s pichawai collection, Ahmedabad

- Mural by Amit Ambalal, Ahmedabad

- HALI Tour group at the Lalbhai Museum, Ahmedabad

- Steven Cohen explains ‘Sahib, Bibi, Nawab: Baluchar Silk of Bengal (1750-1900)’, TAPI Collection exhibition at the Lalbhai Museum, Ahmedabad

- ‘Sahib, Bibi, Nawab: Baluchar Silk of Bengal (1750-1900)’, TAPI Collection exhibition at the Lalbhai Museum, Ahmedabad

- ‘Sahib, Bibi, Nawab: Baluchar Silk of Bengal (1750-1900)’, TAPI Collection exhibition at the Lalbhai Museum, Ahmedabad

- ‘Sahib, Bibi, Nawab: Baluchar Silk of Bengal (1750-1900)’, TAPI Collection exhibition at the Lalbhai Museum, Ahmedabad

- ‘Sahib, Bibi, Nawab: Baluchar Silk of Bengal (1750-1900)’, TAPI Collection exhibition at the Lalbhai Museum, Ahmedabad

- ‘Sahib, Bibi, Nawab: Baluchar Silk of Bengal (1750-1900)’, TAPI Collection exhibition at the Lalbhai Museum, Ahmedabad

- Hutheesing Haveli

- Hutheesing Haveli

- Dancers at Hutheesing Haveli

- Private collection, Hutheesing Haveli

- Heritage walk, Ahmedabad

- Heritage walk, temple, Ahmedabad

- Wooden door, heritage walk, Ahmedabad

- Architectural details, heritage walk, Ahmedabad

- Architectural details, heritage walk, Ahmedabad

- Mosque, 15th century, Ahmedabad

- Mosque, 15th century, Ahmedabad

- Mosque, 15th century, Ahmedabad

- Mosque, 15th century, Champaner

- Mosque, 15th century, Champaner

- Mosque, 15th century, Champaner

- Mosque, 15th century, Champaner

- Mosque, 15th century, Champaner

- Mosque, 15th century, Champaner

- Mosque, 15th century, Champaner

- TAPI Collection, Surat

- Ladies procession, kalamkari, circa 1430-1530, TAPI Collection, Surat

- Figural hanging showing a royal procession, Coromandel Coast for export to SE Asia, mid to late 17th century, TAPI Collection, Surat

- Ceremonial cloth, Coromandel Coast for export to SE Asia, 18th century, TAPI Collection, Surat

- Chintz jacket for export to France, circa 1790, TAPI Collection, Surat

- Chintz for the Thai market, TAPI Collection, Surat

- Chintz floorspread fragment, circa 1640, TAPI Collection, Surat

- Red and gold velvet tent hanging from the Mughal court, TAPI Collection, Surat

- Kashmir shawl fro the European market, circa 1800s, TAPI Collection, Surat

- Armenian and Dutch cemetery, Surat

- Armenian and Dutch cemetery, Surat

- Armenian cemetery, Surat

- English cemetery, Surat

- English cemetery, Surat

- English cemetery, Surat

- Vishnu as Narayana, circa 1790, CSMVS (former Prince of Wales Museum)

- Indian cotton cloth, 1200-1400, found at Qasr Ibrim in Egypt, The British Museum, ‘India and the World’ exhibition at CSMVS (former Prince of Wales Museum)

- Kalamkari textile, circa 1500, Gujarat, found in Sulawesi, Indonesia, ‘India and the World’ exhibition at CSMVS (former Prince of Wales Museum)

- Kalamkari textile, circa 1500, Gujarat, found in Sulawesi, Indonesia, ‘India and the World’ exhibition at CSMVS (former Prince of Wales Museum)

The first HALI Tour to India visited Rajasthan and Gujarat, where forts and folk-art foundations helped to contextualise the world class textiles found in courtly and private collections. An abridged version of the following account by Tour Manager and HALI Assistant Editor, Rachel Meek appears in HALI 195.

Kantha, patola, phulkari, pichawai, kalamkari are terms I first encountered while assisting Karun Thakar, ahead of the publication of several books on his collection by HALI. As he unfurled and explained these textiles in his home on the south coast of England, I appreciated them. But Indian textiles look different in India and it was there, during the recent HALI Tour, that such pieces really engaged me and were revealed as being only the tip of a textile iceberg.

It was clear from the outset that the first HALI Tour to India would be insightful. Our second collaboration with Martin Randall Travel was led by the Indian textile aficionado Rosemary Crill, who has travelled to the country on at least fifty occasions. Her name, in tandem with our guest lecturer Steven Cohen’s, has also appeared a staggering 300 plus times on the pages of HALI over the years. The opportunity to view courtly and private collections of northwest India in their company was eagerly anticipated by myself, acting as tour manager, and the 22 guests from the USA, Australia and South America who arrived in Delhi in February to participate in the fully booked 13-day tour. A series of plane, train and coach journeys would take us from the capital to Jodhpur and Jaipur in Rajasthan, the heartland of Rajput culture, and then on to Gujarat: home to an overwhelming array of local textile traditions as well as two of the greatest collections of historic Indian textiles built up in more recent times—The Sarabhai Collection at the Calico Museum of Textiles in Ahmedabad, and the TAPI Collection in Surat.

The complexity of Indian history—and therefore its textiles—was demonstrated on day one, by a guided stroll around Lodi Gardens, where elaborate 15th century tombs, inspired by Persian gardens with Afghan-style domes and turquoise tiles, are set in a British-designed garden—the creation of which, in the 1930s, displaced two villages. Delhi also delivered two of four temporary exhibitions that coincided with our tour; two of which had been extended especially for our visit. At the National Museum, Anamika Patak the curator of ‘Ramā-Abhiramā: The Beauty of Ramā in Indian Art and Tradition’ introduced the deeds of Hanuman, the greatest devotee of Rama—the seventh incarnation of Vishnu—through Hindu miniatures, sculpture, costume and an unusual embroidered indigo temple hanging from Karnataka or Tamil Nadu displayed in its full ten metre glory. Scenes from the Hindu epic are an incredibly popular subject matter in multiple textile techniques, as we were to discover, but these Jain style figures with protruding eyes combined with folk-art style outer panels made for an intriguing first encounter.

Over at the National Handicrafts and Handloom Museum, Leika Poddar patron of the Devi Art Foundation, welcomed us to ‘A Search in Five Directions: Textiles from the Vishwakarma Exhibitions’; the show it produced in collaboration with the museum in memory of Martand Singh—the mastermind behind this 1980s exhibition series who died last year. Rosemary remembered some pieces from the 1982 Festival of India at the RCA in London which showcased the best of modern Indian production following a period of rapid industrialisation, resulting in a quality crisis. But they have remained hidden from view ever since and this was the first time they have ever been shown in India. While impressive in themselves, the 20th century textiles also provided a benchmark for comparison with the highly accomplished historic textiles that were to come.

It is worth mentioning that, although the concept of connoisseurship and collecting did exist for private pleasure among the wealthy, public museums are a relatively recent phenomenon in India; Delhi’s National Museum opened in the 1950s in the building that had been the president’s house. Traditionally, domestic textiles were reused and recycled rather than saved; the goldwork from saris was melted down for dowries, and textiles in the extensive Rajput collections were classed as collateral wealth. Kept in storage, certain pieces might be brought out at opportune moments to impress appreciative courtiers and dignitaries and a private visit to the store rooms of Jodhpur’s Mehrangarh Fort revealed shelves of court costume, still laying wrapped, in protective layers of muslin and pest-repellent neem leaves.

Occupying an imposing hilltop position above the city, the building provided an impressive back drop to our breakfasts in the garden restaurant of the Raas Hotel. Started by Rao Jodha of the Rathore clan in the mid 15th century, additional sections were added over the next 400 years. Metal rings mounted along the red sandstone walls of the fort courtyards await lavish awnings and drapes, some of which are displayed in the museum. A large scale woven hanging with a bold floral design on a solid gold background of metallic thread made a lasting impression, as did a reed screen of the kind described by a French visitor in 1679 as being used to ‘prevent flies from tormenting the horses’. These stable hangings are intricately decorated—each reed wrapped in silk thread, in the manner of the Central Asian screens of a much larger scale, forming an overall floral lattice pattern. At our second fort visit, to Amber near Jaipur, no textiles remain, but iris flowers carved into marble panels of the winter palace were instantly recognisable from designs on the spectacular carpets we had seen at the Jaipur City Palace and the Albert Hall Museum the previous day.

And what carpets they were. We were shown not one or two, but three unusually shaped, Indian made pile carpets, that are not usually on show, with labels dating from the 17th century; the time that they entered the palace inventory, and when significant extensions were made to Amer Fort. Two at the City Palace, presented by by the Royal Jaipur curators Pankaj Sharma and Aparna Andhare, were laid out on a rooftop in the private quarters, alongside another two carpets, one Persian the other Indian, sporting typically Indian trailing racemes and pink flowers without outlines, placed directly on a rich, cherry-red ground which just glowed in the sunlight. This particular colour results from a combination of lac and madder dyes, and we considered that the outdoors might have originally been their intended setting; backed, as they are, with protective cloth they would sit nicely around a circular campaign tent. Steven Cohen got excited and was quick to point out that, despite the profusion of these rugs on that day, this was certainly not an everyday encounter. The Albert Hall Museum, spurred on by the presence of the world authority on their rug holdings, even organised for the cumbersome frames of heavy clouded glass to be removed from the displays and some rarely seen pieces to be unearthed from the stacks, allowing an unprecedented viewing in their carpet gallery, which also happens to contain the famous, Persian ‘Jaipur Garden Carpet’ (HALI 171, pp. 62-69). The juxtaposition of Persian and Indian carpets at both venues demonstrated the influence of the Mughal court on the Hindu Rajputs who readily adopted the Muslim practices of gifting robes of honour as well as commissioning pile carpets (not an Indian tradition) from the 16th century.

From Jaipur, we flew to Ahmedabad in Gujarat, where the Calico Museum held the highest concentration of treasures. Despite the notoriously strict admissions policy, we were delighted that Rosemary was permitted to provide a running commentary as we were guided through the dark maze of heritage interiors that house the encyclopaedic collection. By now, we had also visited textile museums at two private foundations set up in the mid 20th century to champion everyday items and revive local folk crafts: the Sanskriti Foundation in Delhi which hosts regular artists residencies—where we were honoured to chat with the founder, O.P. Jain over tea—and the Shreyas Foundation in Ahmedabad which doubles as a creative Montessori school. The Calico Museum’s educational technical galleries aided our understanding of our ever increasing arsenal of terminology: woven jamdani, tie-dyed bhandani odhani, mochiwork in cobbler stitch and reverse sided cotton and silk mashru.

In the same city we received a lavish reception at the Hutheesing Haveli, where antique royal costumes from the private foundation’s collection were showcased, and Amit Ambalal welcomed us to his home to view his pichawai collection, artfully presented in a 16th century wooden temple from Burhanpur: saved when it was demolished to make way for a concrete replacement and re-erected in his garden. The artist explained that he was first drawn to historic textiles in a practical sense while looking for inspiration for his own work. We also visited our third temporary exhibition—’Sahib, Bibi, Nawab: Baluchar Silk of Bengal (1750-1900)’, in which figurative saris from the TAPI Collection depict amusing observations of changing times–Mughal aristocracy mixing with the English men and women who had arrived with the East India Company.

The tour culminated with an entire day dedicated other elements of the TAPI Collection in Surat. The three themed selections arranged by Rosemary were cause for much admiration from the group, the TAPI staff and Suhail Shah, the collector’s son, who all attended to hear her commentary on the textiles: all at the pinnacle of their type. We traced the development of the boteh motif through time, and recognised similarities between the patterns on a 14th century Gujarati trade cloth destined for Sulawesi in Indonesia and the swirling arboreal stone carvings seen at Ahmedabad stepwell and the mosques in Champaner. A final train journey delivered us to Mumbai from where we were to embark on our scattered homeward travels, where there was chance to catch one final exhibition ‘India and the World: A History in Nine Stories’ at the CSMVS (former Prince of Wales Museum).

Alongside the finest historic textiles (augmented by shopping opportunities and lectures from Rosemary and Steven), we also witnessed the continuation of northwest Indian textile traditions. The sight of dozens of village women in tie-dyed headscarves arriving into Jaipur on the back of tractors for a mela demonstrated how pieces in museums are meant to be (and are still) used. Roopraj, an enterprising dhurrie weaver, provided a flat loom demonstration and explained the success of his social weaving project involving fifty villagers. We saw complex patchwork compositions at a factory recycling textiles on a commercial scale, although the extant value of some complete pieces was thankfully being recognised—a hoard Hissar shawls had been set aside. The producer of some of the finest new block printed textiles in India, Brigitte Singh highlighted the astonishing virtuosity of early pieces during an atelier tour.

I returned to England with a deepening respect for the myriad of decorative textile techniques we encountered daily and of the ongoing, bold application of these in India, which for centuries has set such a fine example of how to adapt to trade demands and assimilate attractive exotic elements with style and finesse. Many thanks to our guides and all those who greeted us with warmth, generosity and a willingness to share and exchange knowledge, making the first HALI Tour in India such a delight. This HALI Tour will be repeated 9-22 February 2019, email halitours@hali.com for further details or book online via Martin Randall Travel.

Comments [0] Sign in to comment