Distant Neighbour, Close Memories: 600 years of Turkish-Polish Relations

As Turkey celebrated her 600-year friendship with Poland – dated from their first recorded treaty in 1414 – Istanbul’s Sakıp Sabancı Museum held an exhibition, recently ended (7 March–15 June 2014), of Ottoman works of art and Polish imitations drawn from both Polish and Turkish collections.

Penny Oakley reports: The exhibits fell roughly into three categories: clerical; military; court and diplomatic. The Church often adapted Ottoman textiles to suit liturgical roles, and the most splendid vestment was a cope of Bursa velvet with hood and orphreys of Polish embroidery. Its ogival carnation design seems to be unique, with sprays of stems each bearing a trio of çintamani balls, rather than the more predictable flowers.

Cope, Ottoman çatma, silk and metal-wrapped thread, Turkey, probably Bursa, 17th century; embroidered hood and orphreys, Poland, second half 17th century. 1.26 m x 2.75 m (4’ 2″ x 9’ 0″). Carmelite church, Piasek, Cracow

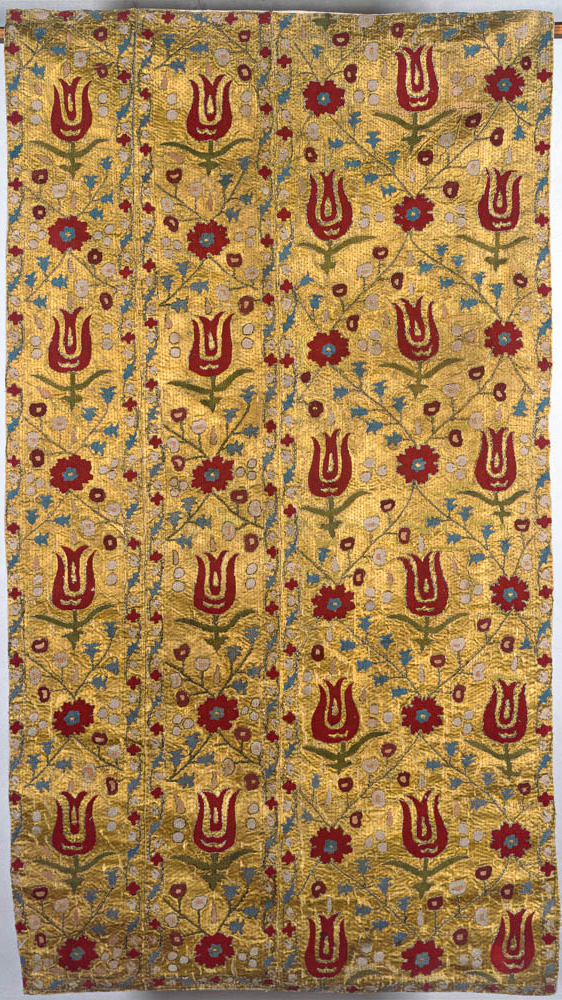

Staring at a long vitrine with its procession of thirteen chasubles felt a bit like holy window-shopping at an ecclesiastical outfitter. One was fashioned from a matching pair of yastıks (cushion covers) in the costly gold and silver fabric called seraser, with sprays of roses or peonies. The yastık format is recognisable from the lappet end-borders.

Chasuble, Ottoman seraser (silk, silver and gilt thread), 17th century. 0.92 m x .070 m (3’ 0″ x 2’ 4″). Formerly in Turobin parish church, Archdiocesan Museum of the 200th Anniversary, Lublin, MAL 16A/05.

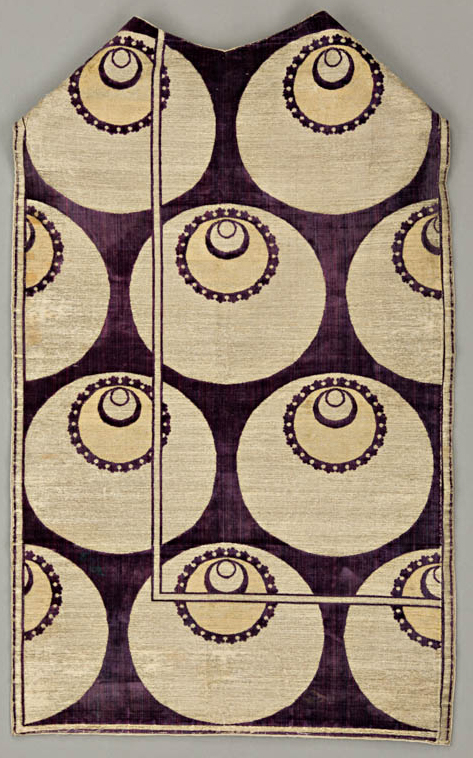

Another chasuble was cut from a purple çatma velvet double panel, with an implied border laid over offset rows of huge silver and gilt çintamani. Taken from the left half of the original, so that the guard-stripe lay over the left shoulder, the effect was mildly eccentric.

Chasuble, Ottoman çatma, probably Bursa, late 16th/early 17th century. Made from the left-hand half of a large velvet double panel with an implied border, with offset rows of çintamani, the central section of each with a trefoil outline. Silk and metal wrapped thread, 1.04m x 0.66m (3′ 5″ x 2′ 2″). St Adalbert Church, Kościelec Pińczowski

A third chasuble had orphreys cleverly pieced from a rare type of Ottoman velvet yastık with inscribed cartouches.

The Ottoman style became so popular in Poland that even the uniforms were the same. Trade with Poland was welcomed, particularly as she paid for her purchases with silver coin – the bullion so vital to the Ottoman exchequer.

The demand for Ottoman goods became so great that Poland eventually imported Ottoman craftsmen to set up their own ateliers and train the local artisans, just as the Ottomans had once brought Persian artists to Istanbul.

Polish Ottoman-style appliqué wall hanging with the arms of Adam Mikolaj Sienawski. 186 x 246cm, National Museum, Warsaw. 82. SZT1980

A Polish rug shows that carpet weaving was another Ottoman import. Like its pair in the National Museum in Cracow, it bears the trophied, impaled arms of two noble Polish families linked by marriage, Potocki and Mniszech, with the insignia of the Grand Crown Hetman, a political title assigned to military commanders. The design is more occidental baroque than oriental, and is related to the Sarre Polish rug (Erdmann, Seven Hundred Years of Oriental Carpets, p. 216, pl. 281), which has similar minor borders, and also to a pair in Cracow.

Carpet with the trophied and impaled arms of Mniszech and Potocki and the insignia of the Grand Crown Hetman, Poland, first half 18th century. Wool pile, flax warp and weft, 2.09 m x 1.42 m (7’ 10″ x 4’ 8″). National Museum, Warsaw, MNW, inv. No. SZT 592

Even the best of friends fall out sometimes. The exhibition’s martial content inevitably involved the 1683 Siege of Vienna and the rout of the Ottoman forces. It was one of history’s more significant battles, denting the image of Ottoman invincibility, and marking the start of the Ottoman decline. Unusually, the Poles fought with the Habsburg armies against the Turks. Duty-bound to support the Holy Roman Emperor, they were also piqued by Ottoman incursions into ‘their’ western Ukraine (Muscovy held sway over the eastern part, so nothing much has changed).

Ottoman embroidered caparison, first half 17th century. Parish Church of All Saints in Goljewek, Archdiocesan Museum, Poznan, MAP 01-3810

The hero of the hour was King John III Sobieski of Poland, commander-in-chief of the European forces, who took home 400 wagon-loads of booty, including palatial tents. Visitors to the exhibition saw only one small tent, from Wawel Castle, flanked by caparisoned warhorses. All the panoply of war was there: ornate saddles and covers, bridles, stirrups, swords, bows and arrows, helmets, chain mail, embroidered boots, shields, cymbals, drums, and even examples of the tug, the Ottoman horse-tail standard. The combined effect gave one some idea of the grandeur and visual impact of a major battle.

Otherwise, the exhibition covered the court and diplomatic aspect largely through images and documents recording incidents and activities involving the two states, and splendid diplomatic gifts that demonstrated the mutual respect between the sovereigns. The illustrated catalogue has a series of useful essays, some better translated than others.

Comments [0] Sign in to comment