Making Connections: the Role of Archives

In recent years, the opening up of museum and private archives, with increased online access to collections and information about them, has allowed textile researchers such as Ann French to build a more detailed picture of the interconnections between, and the methods used, by the early collectors of Greek embroidery. The article below was written by Ann French and first published in HALI 202.

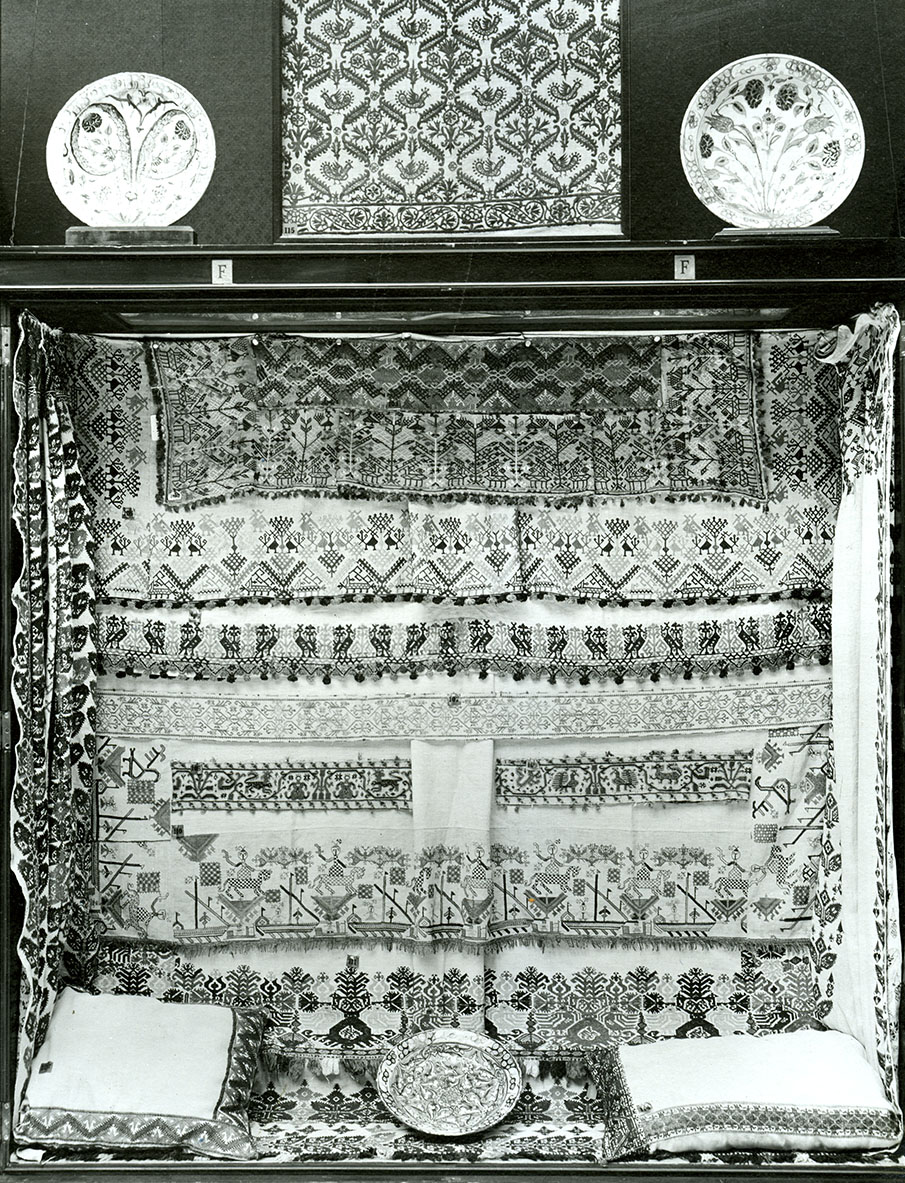

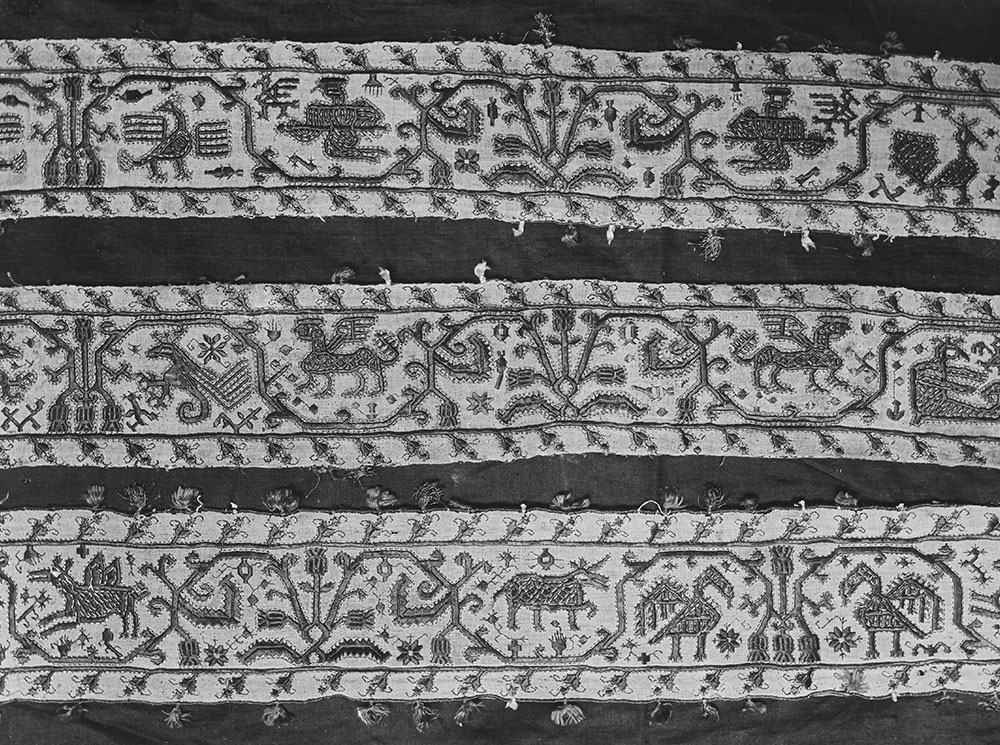

Case F in the 1914 Burlington Fine Arts Club exhibition ‘Old Embroideries of the Greek Islands & Turkey’, with two sections of Melos embroidered border in the third register from the bottom. Described as: ‘Cyclades (Melos) 108, 109. Two portions of a Border embroidered in satin stitch in red silk and gold thread on linen, with a floral zig-zag pattern enclosed by straight lines edged with leaves set obliquely. In either side of the zigzag are sirens, peacocks and and various types of dragons or griffins. Lent by Mr R.M. Dawkins’

In HALI 36 (1987), Roddy Taylor introduced ‘The Early Collectors’, an account of and introduction to the early collectors of historic Greek embroideries, and to the public collections in which most of their embroideries now reside. An extended version of this article was reprised in his book Embroidery of the Greek Islands (1998). In each publication, one of the principal collectors highlighted was my grandfather, Alan J. B. Wace, Keeper of Textiles at the Victoria and Albert Museum from 1924 to 1934. Much of the information Taylor drew on was in the published domain of the time. Since then, with the opening up of museum archives, online availability of collections and access to others including family archives, a more complex picture of the interconnections, academic influences and research methods behind the early collecting of Greek embroideries is gradually emerging.

This ongoing research is rooted in archives and collections, piecing together survivals and regretting the impact of lost letters and weeded registry files. The long-term aim is to (re)catalogue the Wace and Dawkins Collections of Greek embroideries to reveal this wider picture within their cultural perspectives and influences, thereby (re)positioning the embroideries so that different, further and more local narratives might merge. This article expands on the archives consulted and their limitations, and then follows a single Cycladic (Melos) embroidery through the archives and subsequent publications. Using such a single example, the narrative trajectory from collection to contemporary display and publication uncovers changes of interpretation and value.

E.W. Webster, A.J.B Wace and R.M. Dawkins, Greece, 1902-03. Annotated on the reverse in Wace’s handwriting: ‘Left to right E W Webster AJ B Wace R M Dawkins sitting on top of ruined tower at entrance to fort, Phyle. Dawkins holds the bread, I the newspapers & Webster the olives wrapped in paper’. Wace Family Collection

When Wace sold the bulk of his Greek embroideries to Liverpool Museums in 1956, a large quantity of paperwork and photographs was also dispatched with the embroideries. These were stored in six herbaria boxes in a state of benign neglect, being consulted by visiting scholars who attempted to make sense of the contents and Wace’s handwriting.

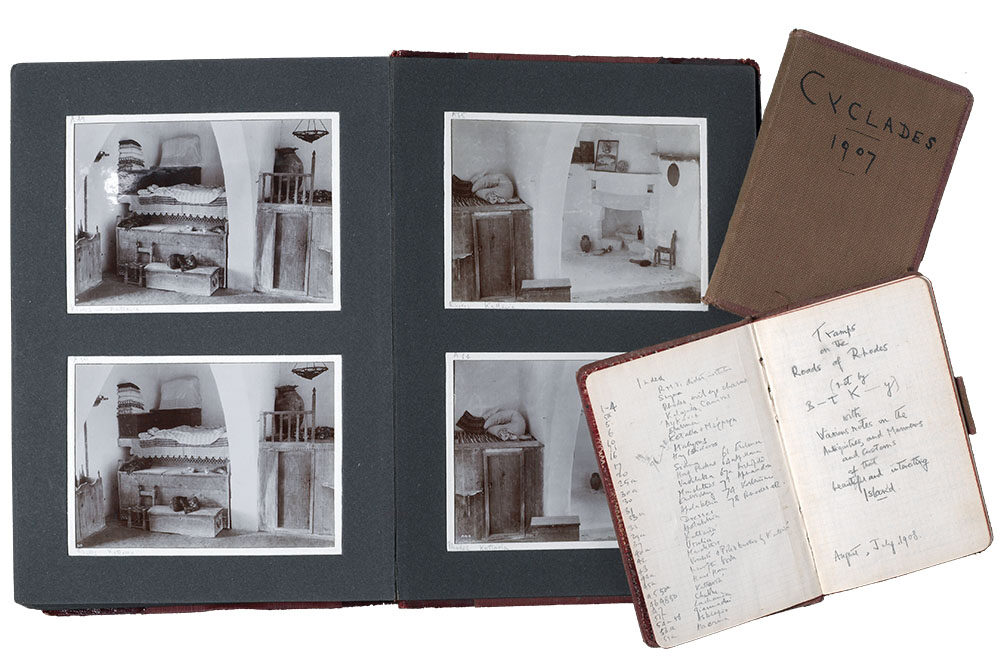

When I first encountered them in 2005, the disorder was plain, but nearly fifteen years later with a better mastery of Wace’s handwriting, narratives and connections are emerging. The archives in Liverpool include: Wace and his collecting colleague Richard M. Dawkins’ initial cataloguing notebooks, one travel notebook, photographs of their collections, photographs of their collaborators’ embroideries, photographs of museum collection pieces, some correspondence, a full labelled set of the photographs of the 1914 Burlington Fine Arts Club Exhibition, ‘Old Embroideries of the Greek Islands & Turkey’, the proofs of Wace’s Mediterranean & Near Eastern Embroideries (1935), a draft manuscript by Wace and Dawkins describing their research and a set of every publication written on the subject up to 1956, including Italian contributions from the era of Italian dominance of the Dodecanese from 1922-45. There is no sense of a formally compiled archive—it appears as if anything that was connected to Greek embroideries was swept up and sent off by Wace’s family in 1956.

Additional archival material has also emerged in other institutions—correspondence in the V&A Archive nominal files with A. F. Kendrick (Wace’s predecessor at the V&A) and Anthony Benaki, with John Linton Myres in the Bodleian Library, with George Hewitt Myers at the Textile Museum in Washington, DC, with Sir William Ridgeway (Wace and Dawkins’ professor and mentor) at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, and others at the British School at Athens and the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. Further material was deposited in the Bodleian, Oxford after Dawkins’ death in 1955, including his travel notebooks, and some material was retained by Wace’s family.

The questions many have posed about Greek embroideries are not answered by any of the protagonists found within these archives—such as why collect so many and so prolifically—nor is there any evidence of a more modern anthropological-style record. The picture that does emerge, however, is one of a wide network of interests and support behind such collecting and of the information recorded. Dawkins and Wace were not alone in their collecting and they received much help and encouragement. They were behind the ground-breaking exhibition at the Burlington Fine Arts Club in 1914 and its associated publications, but they never published their draft manuscript and Wace is more remembered for his catalogue of another’s collection—that of Mrs Frank Cook.

The archives reveal their catalogue recording systems, which are clearly rooted (and use the same notebooks from the same stationary supplier) in their archaeological practice. A number of photographs of pieces belonging to others including A .M. Daniel and Miss Welsh reveal another cataloguing system similar to that refined by Louisa Pesel in her Portfolios of Stitches. This latter (rather superior) system includes noting materials, colours, stitches and ‘class’, as well as place and date of purchase that predominate in Wace and Dawkins’ notes. The album of photographs, and loose photographs, widen the collecting network and include embroideries collected by Duncan Mackenzie, Georg Karo, A. M. and Marjorie Daniel, Carl Blegen, Robert Carr Bosanquet, Ellen Bosanquet, George Dickins, Louisa Pesel and Miss Welsh. The correspondence between Wace and Kendrick exposes the use of such photographs—they were swapped around and exchanged as a sort of reference system to guide identification, and to know what pieces existed where.

Pholegandros pillowcase (detail). This piece is listed as: ‘502 Hydra Widow RMD2, GD2. Fine polychrome—pattern in satin stitch recalls 4 somewhat and also Cycladic n.87 bed curtain of borders. Daisies on edge suggest S. Ken. Island. It was cut into 2 pillows & 2 mostras— we saw the 2 mostras in Pholegandros’. Dawkins’ pieces are now in the V&A (T.87&A-1950) and one was on display for many years in the V&A Textile Study Rooms. ‘GD’ refers to George Dickins who was part of the group at the British School in Athens investigating embroideries and was killed on active service in 1915. A near identical piece is V&A T.121-1939, which belonged to the designer William Morris, and whose daughter May Morris bequeathed it to the museum. It may have been acquired by Morris at the same time as two pieces of Cretan embroidery ‘brought back by the English consul’ which Morris sent to Thomas Wardle in 1876 stating ‘Mrs Wardle will find some stitches in them worth looking at’. Wardle was one of the leading British textile manufacturers of the later 19th century, and his wife a noted embroiderer. Morris’ piece is illustrated in Pauline Johnstone’s Guide to Greek Embroidery, and in Greek Embroidery 17th-19th Century: Works of Art from the Collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum (2006 ) by Tatiana Ioannou-Yannara. However Wace’s piece, now in the Wace Family Collection (4), is given one of the few colour plates (p.96) in Symonds & Preece, A History of Decorative Needlework, where it is described as: ‘Embroidery, formerly part of a bed curtain from the Cyclades (probably Pholegandros). The curtain was cut up and made into two pillowcases and two bed valances. The piece illustrated belonged to one of these pillowcases, both of which had come into the possession of a dealer in Athens. The bed valances which correspond to it were extant in 1907. The linen is very fine, some 80 threads of warp and 70 weft to the inch. The stitches are darn, satin, cross and plait, with coloured silks. Greek, 17th century’

While photographs provided many embroideries with an identity to use when tracking their current location, many original labels survive on the embroideries themselves in either Wace or Dawkins’ handwriting. These labels directly connect the embroideries to their written notebooks enabling a clearer provenance to emerge. Those bought directly off owners can be distinguished from those bought in Athens, Constantinople, Smyrna, London or Paris. Some additional labels survive on the embroideries—those of the Burlington Fine Arts Club and a few from a loan to the West Riding Embroidery Association for Louisa Pesel.

Melos embroidered border fragment, Wace 819. Described by Wace as: ‘Emb Long strips—red— gold edged—satin narrow border faced both edges Italian wave pattern with beasts in waves—sirens (2), Eagles (2), Peacocks various types, deer, jugs? &varia. Graecised Italian animals. Alas not ours’ Wace Family Collection

This preservation together of labels and notebooks raises the issue of what conservators call the 10th Agent of Deterioration—Dissociation. Dissociation describes the loss of object-related data and therefore the ability to retrieve or associate objects and data. It affects the intellectual, and/or cultural aspects of an object as opposed to the other ten agents of deterioration (light, temperature etc.), which mainly affect the physical state of objects. Dissociation is a metaphysical agent and is prevented by maintaining and appreciating archives which make connections possible.

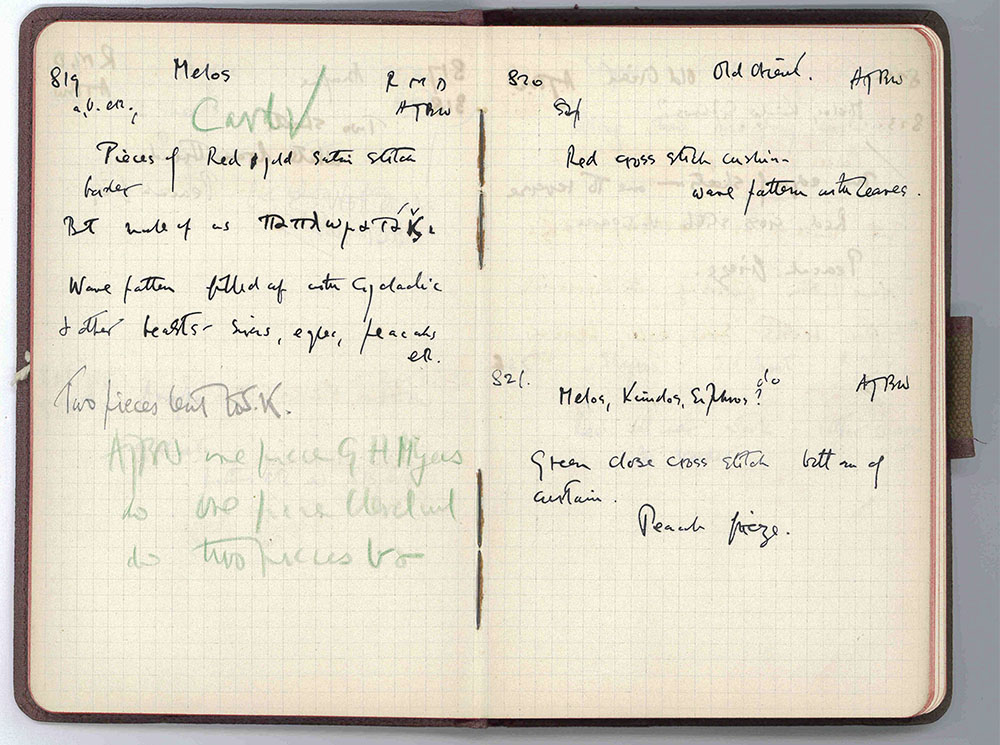

Page from Wace’s Embroideries Notebook, ca. 1907, now in Liverpool Museums, which reads: ‘819 a,b, etc Melos RMD AJBW Pieces of red & gold satin stitch border Bt made up as παπλωματακι Wave pattern filled up with Cycladic & other beasts—…eagles, peacocks etc’. A later pencil note reads: ‘Two pieces lent KS A’. A green pencil note has a tick and ‘card’ written: ‘plus AJBW one piece GH Myers, ditto one piece Cleveland, ditto two pieces V&A’

The final photos found in Liverpool (and elsewhere) are those taken of the 1914 exhibition at the Burlington Fine Arts Club. Those in Liverpool, however, have the corresponding numbers written on them—in Wace’s handwriting—another link connecting records and publications back to the embroideries.

In a few cases, it is therefore now possible to track a single item from collection to current location, along with the shifting and evolving interpretations given it—a form of object ‘biography’.

In Wace’s Cyclades 1907 notebook, which covers a tour undertaken with Dawkins to the islands of Siphnos, Kimolos, Melos, Pholegandros, Sikinos, Ios, Anaphe, Keos, Naxos, Paros and Antiparos, he notes that they arrived on Melos by ferry on Thursday July 11th 1907, and they left on 10th August 1907. After various notes on other embroideries and a few inscriptions, an entry reads: ‘Emb Long strips—red—gold edged— satin narrow border faced both edges Italian wave pattern with beasts in waves—sirens (2), Eagles,(2), Peacocks various types, deer, jugs? & varia. Graecised Italian animals. Alas not ours’. It does not, however, feature in Dawkins’ travel notebook which is more preoccupied with noting local dialects and certain architectural features.

Photographs from Wace’s albums, together with his 1907 Cyclades 1907 notebook. Wace Family Collection

The subsequent catalogue entry in Embroideries Notebook 5 (circa 1907) now in Liverpool, lists in Wace’s handwriting the pieces as: ‘819 a,b, etc Melos RMD AJBW Pieces of red & gold satin stitch border Bt made up as παπλωματακι Wave pattern filled up with Cycladic & other beasts—… eagles, peacocks etc’. A later pencil note reads: ‘ Two pieces lent SK’. A green pencil note has a tick and ‘card’ written: ‘plus AJBW one piece GH Myers, ditto one piece Cleveland, ditto two pieces V&A’. Dawkins’ copy of this catalogue, now in the V&A and dating from the 1930s, lists in Wace’s handwriting again: ‘819 a,b, etc Melos RMD AJBW Pieces of red & gold satin stitch border— bought made up as a παπλωματακι Wave pattern filled up with Cycladic & other beasts—sirens, eagles, peacocks etc’.

Two pieces of the embroidery feature in the 1914 Burlington Fine Arts Club exhibition catalogue Old Embroideries of the Greek Islands & Turkey. Both the pieces used for the display are those of Dawkins and are described as: ‘Cyclades (Melos) 108, 109 Two portions of a Border embroidered in satin stitch in red silk and gold thread on linen, with a floral zig-zag pattern enclosed by straight lines edged with leaves set obliquely. In either side of the zig-zag are sirens, peacocks. And various types of dragons or griffins. Lent by Mr R. M. Dawkins’.

In a catalogue, now in the Liverpool Wace Archives, probably dating from the mid 1920s, in which he unhelpfully re-numbers his collection, Dawkins notes: ‘354 to 361 strips with wave pattern and animals in red and gold thread. These were bought in Melos in 1907 with Wace who has a similar lot. They were all sewn together into a quilt, paplomataki, but probably are from a curtain. No joins were possible so we divided the lot, and the absence of joins, unless the pieces were trimmed to fit into the quilt suggests that the original piece was quite large’. These pieces do not feature in the special 1921 edition of The Studio complied by A. F. Kendrick, Louisa Pesel and Essie Newberry and featuring many pieces from Wace’s, Pesel’s and the Newberry’s collections.

Epirus (?) border fragments Listed in the catalogues as: ‘495 RMD O.O.“Jannina” from Paros, Bought sewn onto 494 (RMD) fragments of a Cycladic bedcurtain of leaf pattern-floral type. Jannina style & colours but fringe of legless cavaliers on horses between trees. 495a AJBW Scraps of same.’ This purchase, from the dealer Old Orient, of a Cycladic bedcurtain repaired with scraps of very different embroidery clearly puzzled Dawkins and Wace and led to a number of attributions for the provenance of this embroidery. They were noting dialect differences in spoken Greek on their travels which they felt reflected population movements, and may well have linked finding a northern embroidery on a Cycladic piece to such movements. The Dawkins piece (now V&A T.431-1950) was exhibited in Case G at the Burlington Fine Arts Club Exhibition, described as, ‘122 BFAC North Greek Islands (Paros) Border embroidered in darning stitch in coloured silks on linen with a pattern of confronted towers of legless cavaliers who are pulling flowers off the trees standing between them. Between each pair of cavaliers there are other trees. The black silk has nearly all perished. Lent by RM Dawkins’. Wace’s piece (9), from the Wace Family Collection, was illustrated in colour (p.51) in A Book of Old Embroidery (1921) by A. F. Kendrick, Essie Newberry and Louisa Pesel. It is now described as ‘Ionian Islands Border of linen embroidered with coloured floss silks in surface darning.’ Dawkins’ re-written catalogue lists his pieces as: ‘515 border of horsemen, good condition but black gone. Unlike the other pieces this has an Italian look and is mended with a fragment of the Cycladic curtains with flowers at 45 degrees. It looks as if it came from the Cyclades and it was said by Old Orient to be from Paros. Wace has a piece. I think when they were bought they had a bit of the 45 degree work with them’. This piece is featured in Pauline Johnstone’s A Guide to Greek Embroidery (p.85) as ‘Part of a border ? Epirus’ and she accurately notes that Dawkins catalogue entry was ‘presumably the description of the dealer from whom he bought it’. Roddy Taylor confuses the issue by illustrating Wace’s piece (p.136-7) in his Embroidery of the Greek Islands (1998) and inaccurately stating that it was bought by Wace and Dawkins in 1901 in Epirus. Both arrived in Greece in 1902, and never visited Epirus, still part of the Ottoman Empire in 1902, together.

In March 1924, Wace’s brother-in-law died, leaving Wace financially responsible for his older sister, a position complicated by the fact he was unemployed at the time and wanted to get married. George Hewitt Myers, founder of the Textile Museum in Washington, DC, bought 45 pieces from Wace for £1,000.00. Myers’ interest was ‘pieces of artistic color and design’. Wace made a selection of pieces to sell to Myers including three Cycladic satin stitch strips. Two pieces of the Melos strip were kept (accession numbers 81.18 & 81.19) in the Textile Museum, now incorporated into the George Washington University Museum.

Myers, however, did not keep all the embroideries dispatched by Wace to Washington as ‘I already had so many that I really wanted only pieces that were better than mine or different from them’. Wace did not want to deal with the issues of re-importing the unwanted embroideries into the UK due to a silk import tax, with the result that several pieces were purchased by the Cleveland Museum of Art under the aegis of Gertrude Underhill, with the Melos piece being added later with an acquisition date of 1929. Its acquisition number is 29-257 and it was last displayed in 1995-6.

Myers’ collection was exhibited at the Century Club, New York in 1928 for which Wace wrote the catalogue. The two Melos pieces Myers had kept were omitted, but Wace notes ‘Italian domination in the Archipelago is reflected in Cycladic embroideries…. It has been noticed that in the Cyclades and in the Ionian Islands the easier cross stitch replaced the more difficult satin , darning and split stitches during the eighteenth century. Many of the Cycladic satin stitch pieces were damaged and faded and so there is every reason to believe that the majority of the embroideries of these classes at least fall into the 17th century.’

The 1920s also saw the attempt by Dawkins and Wace to write a book on their collections. While never published, a chapter in their draft manuscript entitled ‘The Italian Influence’ concentrates on designs and white drawn-thread work but also notes ‘borders’ which are compared to vertical pattern bands seen in Italian medieval paintings which ‘supports the idea that these, now neatly hemmed on each edge, were originally part of curtains’. Wace and Dawkins differentiate such pieces from ‘peasant work’ on the islands stating that ‘upper class patterns’ are found on the Cyclades as a consequence of Italian domination.

Within the archives found to date, there is no further mention of these pieces from Melos. Wace’s book Mediterranean & Middle Eastern Embroideries (1935) was grounded in another collection, that of Mrs Frank Cook, so much of his knowledge was omitted if not relevant to that collection, although he did claim to Myers that he (and his wife) were cataloguing this collection in the ‘most scientific way’.

Ionian Islands embroidered pillow. Listed as: ‘3021 pillow bought by Mme Trojanski, from Jannina is probably the pillow belonging to the sheet in the Royal Scottish Museum & the same style as the Manchester Whitworth pillow’. It hung in Wace’s flat in Athens for many years. It was featured in Symonds & Preece, A History of Decorative Needlework, p.63, as a colour plate and is described as ‘Pillow cover of linen from the Ionian Islands, embroidered in coloured silks, worked mostly in outline stitch, with the effect of a twill weave, some outlines in chain, some in back stitch, a double row of chain stitch for stems, satin stitch in parts, e.g. features and dress patterns; the border is enclosed within two rows of chain stitch. It is part of the bed furniture made by a Greek girl as her dowry, and other portions of the set would match. The subject probably represents the bride and her parents, and it reproduces the dress of the period, in which are traces of ancient characteristics. In the work is Turkish influence; some of the flower forms may be influences by the pottery of Asia Minor, incorrectly called Rhodian ware. A piece in the Royal Scottish Museum, Edinburgh, with a similar design, is part of a border of a bedspread which might well have belonged to the same set as this.’ Wace Family Collection

Dawkins’ entire collection of Greek and other embroideries was left to a somewhat reluctant V&A in 1955, with George Wingfield Digby stating that ‘although enthusiasm for this type of peasant work is likely to decline in the future we should undoubtedly have it adequately represented here and such collections can probably not be made again’. It included seven fragments of the Melos strip, now accession number T.447a-g-1950, with T.447c-1950 being displayed for many years in the Textile Study Rooms.

T.447d-1950 was illustrated in Pauline Johnstone’s A Guide to Greek Island Embroidery (1972) with the caption: ‘Detail from a border. Cyclades, Milos. Silk and metal thread on linen, stain, chain and double running stitches. Monochrome red. The edges finished with tassels of pink silk and metal thread. Attributed to Milos in the Dawkins manuscript catalogue, no 819. 56 x 11 cm Dawkins Collection, T.447D-1950’.

While no mention is made in Johnstone’s main text of such pieces, she had made use of the Dawkins’ running number catalogue in the V&A, but appears unaware of, or does not mention, the archive material in Liverpool, and the other sections of the embroidery in Liverpool, Washington and Cleveland.

Wace sold much of his collection to Liverpool Museums in 1956, including a single piece of the Melos strip, now accession number 56.210.141, which is the only piece to have an original label remaining on it in Wace’s handwriting ‘819b Melos bt there’. Curiously, this strip was not part of the exhibition in the Horseshoe Gallery of Liverpool Public Museums in 1956 that preceded the collection purchase. It does not therefore feature in the catalogue of the display written by Miss Elaine Tankard with Wace’s help. Elaine Tankard and John Iliffe, the director of Liverpool Museums, had both been students at the British School at Athens while Wace was director there between 1914-22.

Ionian Islands pillow. Listed as: ‘1028 Ionian Island long pillow, cross stitch & maglia quadrata. Given by Mrs Cook to HCW’. HCW was Wace’s wife, Helen, whom he married in 1926. Wace Family Collection

The Textile Museum fragments feature in Aegean Crossroads: Greek Island Embroideries in the Textile Museum (1983) by James Trilling, Ralph Hattox and Lilo Markrich. Both are described as: ‘Portion of a border, Cyclades, Melos. Purchased in 1925 from A.J.B. Wace, St Albans.’ This catalogue questions and notes problems with Wace’s assumptions and methodologies, but overlooks the contexts and connections. Sumru Belger Krody omits the pieces from her 2006 study Harpies, Mermaids and Tulips: Embroidery of the Greek Islands and Epirus Region. The pieces are also omitted from Greek Embroidery 17th -19th Century: Works of Art from the Collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum (2006 ) by Tatiana Ioannou-Yannara.

The Liverpool fragment last featured in Roddy Taylor’s Embroidery of the Greek Islands (1998). It is positioned within Italianate embroideries, as being strictly within the Italian tradition but not copied; rather as being worked by Latins and Franks living in the islands but following styles from home. The illustration is captioned: ‘A sheet end of a twisted vine set with sea monsters, winged horses, dragons and other mythical beasts, converted to a ribbon with added overcast edges and tassels. These strips were commonly used in churches draped over icon and bible stands. Another portion of this strip is in the Victoria and Albert Museum (T.447D-1950). Naxos or Melos, before 1750’.

In summary, in July 1907 Dawkins and Wace between them bought at least twelve strips of embroidery on the island of Melos. Using archives, the current location of all twelve has been established together with the networks that enabled this dispersal. One final strip remains with Wace’s family, the Victoria and Albert Museum has seven, Liverpool Museums one, the Textile Museum has two and the Cleveland Museum of Art has one.

The presence (or absence) across published catalogues, photographs, exhibitions and correspondence can, on occasions, be traced for distinctive embroideries. Such connections between archives, exhibitions and publications all construct value, assign worth and form knowledge, and if connected, the subjective nature of interpretation can be traced enabling new ones to be formed.

Comments [0] Sign in to comment