Samuil Martinovich Dudin

At a time when travel is limited, we would like to highlight a man whose research and collecting journeys form the basis for much of our knowledge of Central Asian weaving culture: Samuil Martinovich Dudin. The biographical sketch below was written by Elena Tsareva and first published in HALI 27. As an invitation to explore the HALI Archive, we have made the full feature on The Dudin Collection from HALI 27 open access, featuring spectacular pieces from St Petersburg museums and a detailed analysis of 22 Ersari torbas.

Samuil Martinovich Dudin is one of the most remarkable personalities in the historical study of carpet weaving. An artist by training and a man of surprisingly broad interests with excellent taste, he was among the earliest researchers into the culture of the Central Asian tribes, one of the first ethnographer-collectors, and a pioneer photographer in Russia.

Comparatively little is known of his early life. He was born in 1863 in Rovnoye in Khersonskaya Province, the son of a soldier turned schoolmaster. From an early age he demonstrated an artistic talent which he developed at school and later at Elizavetgradsk College. His studies were interrupted in the 7th form when he was arrested on a political charge and exiled to Eastern Siberia.

In 1892, while in the town of Kyakhta on the Mongolian border south of Lake Baikal, Dudin’s ability as a painter came to the attention of V.V. Radlov, leader of the Orkhonskaya Expedition of the Academy of Sciences and director of the Petersburg Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography. Radlov is best known today for his outstanding work on the folklore of the Turkic tribes of Siberia. He invited Dudin to join the expedition as painter and photographer. Not long afterwards however, as a result of a successful petition on his behalf by Academician G.N. Potanin, Dudin was permitted to return from exile to Petersburg, where he entered the Academy of Arts. After graduation in 1898, he travelled abroad to round off his artistic training.

In 1893, while still a student, Dudin began working at the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, and served there until the end of his life. He became a permanent member of staff in 1911 as scientific curator of the Department of East and West Turkestan Antiquities, head of the Exhibitions and Photography Department, and secretary to Radlov’s circle which was attached to the Museum.

His activities were extraordinarily diverse. Working as a member of the Archaeology Commission of the Russian Committee for the Study of East and Central Asia, he took part in the organisation of various art exhibitions and participated in a number of expeditions to Asia. During 1920 and 1921 he was also a member of the State Expert Commission for the Registration of the State Valuables, and thereafter consultant to the State Hermitage and Russian Museums on questions of applied arts.

Most of Dudin’s research was in the field of Islamic and Buddhist art, and he became a recognised expert on carpets, ceramics and other areas of Oriental applied arts. He published very little, believing that his most important task lay in collecting and classifying ethnographic material. His presentations are characterised by his profound technical knowledge of his research subjects and an insight derived from meticulous observation on his many journeys into the way of life of the tribal people he studied.

His travels in Central Asia resulted from an Imperial Edict in 1895, whereby Tzar Nicholas II established an ethnographic department at the Russian Museum in Petersburg. The Department’s collections were accumulated according to a scientific plan, and undertaken on a fittingly grand scale by the specialists recruited for the purpose. Dudin, whose reputation as an Orientalist specialising in applied arts was already well founded, was invited to form the ethnographic collection for Central Asia. As he had also become known as an enthusiastic photographer, his brief included not only drawing but also photographing the subjects encountered during his projected journeys.

His first trip to Central Asia in 1900 took seven months, during which time Dudin visited Samarkand, Bukhara, Tashkent, Khodjent, Kokand, Margelan and Urgut, collecting material on the indigenous Sart tribes of Russian Turkestan. The second expedition in 1901 included in its itinerary Samarkand, Tashkent, Aushe-Ata, Pishpek, Tokmak, Issyk-Kul, Kashgar and the Alai valley. During this journey, Dudin completed his collection on the Sarts and nomadic Uzbeks, and began to gather material on Kazakhs, Kirghiz, mountain Tadzikhs and the Turkoman. He first encountered the Turkoman tribes whilst en route to Samarkand.

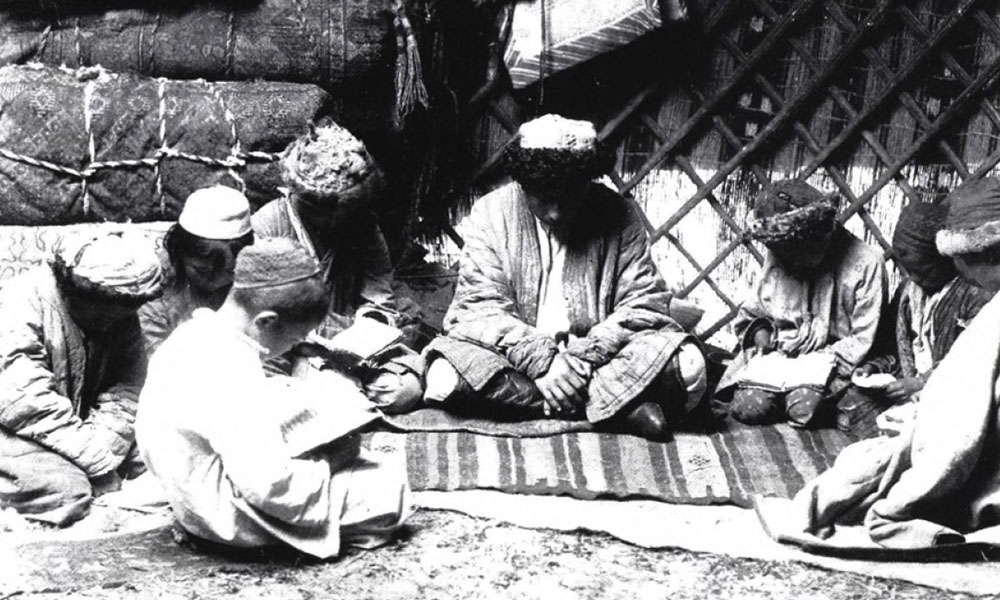

The third Central Asian journey was in 1902, with the stated aim ‘to supplement the gaps in the collections made during the voyages of 1900 and 1901…and there was the need to augment the photograph album begun during my first journey and nearly finished during the second trip’. On his first two expeditions he had bought items made by the Turkoman in the bazaars of Samarkand and Bukhara, but in 1902 he also visited the auls (walled towns) of Ashkabad and Merv, and also the territory of the Sarvk tribe. He wrote during this period: ‘I collected nearly 350 specimens of Turkoman life—mostly Tekke and Saryk’. The photographs from these expeditions are of great scientific and artistic merit, recording what was even then a fast vanishing way of life. In all there were almost two thousand of them, and the surviving photographic collections in museums in Leningrad and Hamburg illustrate many important features of tribal life in Central Asia.

As part of his wider research, Dudin made a detailed study of carpet weaving techniques among the tribes he visited. He developed a comprehensive historical and ethnographical knowledge of the subject. This reflected developments during the second half of the 19th century, when Central Asian carpets were beginning to attract the attention of Europeans, following the final defeat of the Turkoman and the inclusion of their territories into the Russian Empire in 1865, subsequent to which Westerners began to learn about this previously unknown and inaccessible region. Russian officers, often persons of great sophistication and fine taste, were the first to be charmed by Turkoman carpets, many of which were true masterpieces of pile weaving.

The first serious work on Turkoman carpets, Ornaments of the Tekke and their use on Carpets and Embroideries, was published in Petersburg in 1885 by A.A. Astaffyev. It emphasised in particular how Turkoman weavings could be used to advantage in the home. The absence of further publications for a lengthy period was in no way due to any lack of interest in the subject. On the contrary, from 1886 onwards, the carpets of Russian Turkestan were prominently displayed in both the important Russian Industrial exhibitions and in several international exhibitions held in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Private individuals and institutions such as the Stieglitz Museum in Petersburg also began to form significant collections.

Andrei Bogolyubov, formerly Governor General of the Province of Turkestan, compiled a major scholarly work, The Carpets of Central Asia, between 1905 and 1908, which remains to this day of considerable interest and importance. An English translation, edited and with a commentary by Dr. Jon Thompson, was published by the Crosby Press in 1973. Despite its undoubted value, the book was not free of errors and controversial attributions. It certainly provoked the publication of other well-known works such as Carpets of Russian Turkestan (Moscow 1911) by A.A. Semyonov, Antique Carpets of Central Asia (1914/1915) by A. A. Felkerzam, as well as Dudin’s own Carpets of Central Asia, all of which to some degree criticised, corrected and supplemented Bogolyubov’s seminal work.

Dudin’s book was completed in the early 1920s, but remained unpublished until 1928, two years after his death in 1926. It has never been reprinted in Russian and a German translation has only very recently become available, translated by Reinhold Schletzer (Hamburg 1984). It must still be considered to be a fundamental work on the subject. As well as containing substantial amounts of new information, it raised a number of problems of attribution that even now remain unresolved in the subsequent literature.

The lasting worth of Dudin’s ethnographic material lies in the systematic way in which it was compiled. He was successful in fulfilling the defined programme themes, and in supplementing the collections of ethnographic objects with documentary drawings and photographs, thereby forming complex combinations of material of significant research value. Regrettably much of his material, and in particular many of the photographs, ceramics and bronzes were lost when German bombing and artillery almost destroyed the museum building in Leningrad during the Second World War.

Dudin’s collection of Turkoman carpets, tent bags and animal trappings was formed during his three journeys to Central Asia between 1900 and 1902. Only a very small part of it has ever been published until now, although it is undoubtedly one of the most comprehensive Turkoman collections in the world, notable for the beauty of some of the weavings. In all Dudin bought more than 200 carpets and trappings, including over 140 from the Turkoman. These include his own small private collection, 22 items in number, which were presented to the Oriental Department of the State Hermitage Museum in Leningrad by his widow.

The true value of Dudin’s contribution to our knowledge of Central Asia and its peoples was aptly summarised by Academician S.F. Oldenburg: ‘It is not exaggeration to say that in many areas involving the material culture of Central Asia it is impossible today to undertake significant research without the materials of S.M. Dudin.’

The HALI Archive is a fully searchable online resource featuring every issue of HALI since the start in 1978. All HALI print subscriptions include access to the HALI Archive—click here to learn how to get access. We also offer purely digital subscriptions.

Comments [0] Sign in to comment