Tehran’s Treasure Trove

‘Salting’ rug (detail), Qazvin?, central Persia, ca. 1550-1565. Wool pile on a silk foundation with silverwrapped silk thread, 1.65 x 2.33 m (5′ 5″ x 7′ 8″). Carpet Museum of Iran, inv. 254

For its first forty years of existence, external circumstances prevented the Carpet Museum of Iran from revealing its treasures to the world. This year, however, a major exhibition brought the institution back to life. Hadi Maktabi reports on the show and what it means for the museum.

On 11 February 1978, the Carpet Museum of Iran (CMI) was inaugurated, a testament to the country’s proud heritage and excellence in the handicraft it has always been most famous for. The main building was intended to resemble a traditional upright carpet-weaving loom. But by the end of the institution’s first year of existence, the Iranian revolution was in full swing. By the museum’s first anniversary the country was profoundly different.

The oil-rich 1970s had funded an ambitious cultural program led by the Empress Farah who acquired, among other pickings, a string of Safavid carpets from the ‘first golden age of Persian carpets’ as well as the world’s most impressive collection of modern art outside North America and Western Europe. The paintings and sculptures were housed in the neighbouring Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, apart from that handpicked chefs-d’oeuvre that went into Farah’s private collection in the Niavaran Palace. The carpets, all of which she bought on the international market, joined select Qajar-era (1785–1925) masterpieces that were culled from the vaults of the Golestan Palace, residence of the Qajar Shahs; they all formed the startup collection of the newly established carpet museum.

‘Salting’ rug, Qazvin?, central Persia, ca. 1550-1565. Wool pile on a silk foundation with silverwrapped silk thread, 1.63 x 2.40 m (5′ 4″ x 8′ 8″). Carpet Museum of Iran, inv. 253

The museum was set up with a built area of 3,400 square meters and with a designated conservation workshop, academic library, amphitheatre and an education department. It was based in custom-built premises designed by renowned architect Abdol-Aziz Farmanfarmaian on a corner of Laleh Park in Tehran’s chic midtown. High hopes were in store for what was then arguably the world’s most advanced and dedicated carpet institution. But for reasons entirely beyond the control of the founders and overseers, Iran’s carpet museum slipped off the map. Siawosch Azadi’s book Persian Carpets (published in 1977 ahead of the opening) became the only way for the world to see a small selection of the treasures within the museum. No Safavid pieces were included.

In the intervening forty years successive museum directors had little room for action. They certainly had no opportunity to organise a large-scale exhibition. Practically nothing would change in the display year to year, lending a new twist to the term ‘permanent exhibition’. The very same carpets that were chosen for the opening in 1978—mostly weighted towards late 19th-century highlights and subsequently tempered with early 20th-century specimens—continued to dominate the display. Until recently it was a rare sight to see a Safavid carpet in Tehran, and there were better odds of seeing such a venerable old object in the National Museum than the Carpet Museum.

It is thus a tremendously admirable and laudable decision by the current trustees of the CMI that they decided to break with the status quo and put the museum back on the international map where it belongs. Forty years on, the CMI has finally managed to present something befitting its reputation and holdings: a special show titled ‘Forty Safavid Relics: The 40th Anniversary of the Carpet Museum of Iran’.

‘Vase’ carpet, Kerman, South Persia, ca. 1625-1650. Wool pile on a cotton and wool foundation, 3.54 x 4.10 m (11′ 7″ x 13′ 6″). Carpet Museum of Iran, inv. 181

The current director, Mrs Parisa Beyzaee, and local expert Turaj Zhuleh went deep into the museum’s storerooms and identified a number of 16th- and 17th-century carpets that have lain in limbo, unseen, for four decades. The artworks underwent a process of conservation and cleaning before going on display. The National Museum of Iran lent the CMI four additional carpets and three fragments to bring the number up to forty.

Most of these exhibits came to Iran after one dedicated and prolonged shopping spree in the 1970s. It shows how historic Persian carpets had almost entirely left the country for export. This occurred either in the Safavid period itself—the Polonaise rugs of Esfahan and the ‘vase’ carpets of Kerman were, among many others, woven for the export trade—or in the dynamic rush of the second half of the 19th century, which itself triggered the ‘revival’ of Iranian weaving. In a way, this is analogous to the recently opened Azerbaijan Carpet Museum in Baku but quite different from the case of Istanbul’s TIEM or Vakıflar, whose holdings were sourced in Turkey itself.

Kilim, Kashan, 1575-1600. Silk and metal thread tapestry weave, 1.54 x 3.07 m (5′ 1″ x 10′ 1″). Carpet Museum of Iran, inv. 3487

The exhibition lasted from 14 February to 14 March 2018. The Mirzazadeh Carpet Company sponsored the show and supported the conservation project. It also sent forty of its own carpets to the CMI; these were exhibited in the upper gallery of the museum that is usually reserved for temporary displays. Most of these are contemporary works by leading Iranian designers like Karabaghi and Shahsavarpoor of Tabriz and Seirafian of Esfahan. A number, however, are older and go back to the ‘second golden age’ of the period 1870–1920.

The CMI’s founding in 1978 coincided with HALI’s own, and it is a nostalgic twist of fate for the paths of both venerable institutions to overlap again. The museum kindly invited me to visit Tehran for a week as HALI’s representative to study the carpets in the exhibition. The CMI hosted a festive ceremony on the opening day to which the leading lights of the local Iranian carpet community were invited. This included a broad panel of academics, independent scholars and local collectors, in addition to delegates from the Iran National Carpet Centre and the Syndicate of Carpet Dealers of the Tehran Bazaar. A special documentary covering the museum’s forty years was aired with interviews from experts involved in the museum’s forty-year history.

The highlight of the evening was the announcement of the inaugural ‘lifetime achievement prizes in carpet studies’ that the museum’s board has decided to award on an annual basis. On the occasion of the initial ceremony, it was decided that three such awards would be granted simultaneously. They were given to a trio of formidable figures in Iranian carpet scholarship: Siawosch Azadi, Cyrus Parham and Shirin Souresrafil.

Kilim, Kashan, 1575-1600. Silk and metal thread tapestry weave, 1.28 x 3.15 m (4′ 2″ x 10′ 4″). Carpet Museum of Iran, inv. 20830

The Safavid carpets were presented for display in the cavernous main gallery on the ground floor, occupying the central space, while the permanent display of Qajar/Pahlavi-era carpets continued along the peripheral walls. Most of the main strands of Safavid carpet weaving were on show, including some textbook types. For instance, there are seven examples from the so-called ‘Polonaise’ group of silk and metal thread carpets that were woven in the royal ateliers that Shah Abbas I (r. 1587–1629) set up in Esfahan. I do not recall another occasion where I have seen so many side by side.

These carpets were produced in the 17th century for export to Europe as the ultimate in oriental luxury and sophistication. As such the patterns are rather ornate and rely on a simplified set of familiar Safavid tropes such as lotus palmettes, four-lobed compartments and cloud-bands; all are drawn with thick outlining, bold silhouettes and in muted colours. A number of them have new fringes added in the outdated 1970s style, reflecting the period when they were acquired. The variation in execution and quality of the seven ‘Polonaise’ rugs suggests these were either woven at various stages of the 17th century or that different grades were produced concurrently in parallel.

However, when seen alongside carpets from the so-called ‘Salting’ group, the ‘Polonaises’ pale in comparison. The Saltings’ finesse of weave, crispness and sophistication of design, and general excellence is truly impressive. Furthermore, the range of design and pattern across the five ‘Salting’ examples on display testifies to the brilliance and ingenuity of Safavid master weavers. The 79 known ‘Salting’ examples are woven with a wool pile on a silk foundation—with the exception of four which have silk pile—and a high knotting density that varies from 9 to 11 knots per cm length (506–756 knots per square inch). The Salting Carpet after which the group is named was bequeathed by George Salting to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1910 and has a density of 600–756 knots per square inch.

Carpet, Esfahan, 1625-1650. Wool pile on cotton foundation, 2.15 x 4.89 m (7′ 1″ x 16′). Carpet Museum of Iran, inv. 1838

Four of the five carpets are similar in aesthetic and spirit, with elegant elongated calligraphy in the borders and a plethora of motifs of Chinese origin—lotuses and cloud-bands— and others that would come to be landmarks of Safavid design, such as the wild beasts popular in the period of Shah Tahmasp (r. 1524–76), scrolling vines and split-leaf arabesques. The last of the five shares the materials and structure of its counterparts, but differs in aesthetic, being more abstract and almost totally relying on vinery. The Tehran curators attribute this group to Tabriz due to the presence of symmetrical knots found during their analysis. However, it was regrettably not permitted to confirm this matter by hands-on inspection, and Michael Franses has suggested that Qazvin in Central Persia ‘may well be the most likely candidate’ for this group’s production, on account of the fact that Tabriz was either under siege or surrounded by warfare in the years between 1548 and 1655.

Of the other well-known Safavid carpet groups, the ‘vase’ group (usually attributed to 17th-century Kerman since the 1976 publication of May Beattie’s Carpets of Central Persia) was represented by two handsome examples. One is a typical kelleh-format carpet while the other has quite uncommonly squarish proportions. The latter’s drawing and scaling, in tandem with the more generous width (three and a half metres), allow the motifs to space out, giving a new perspective on what has become a recognisable group. The kelleh ‘vase’ carpet remains, however, an excellent example of type with acute detailing and richly compact composition.

A very fine small silk Kashan rug is closely related to the celebrated Altman silk Kashan piece with animals at the Metropolitan Museum. Another two examples with wool pile on silk foundations share similar designs. Wild beasts roam across their landscapes and engage in combat in richly-designed scenes that seem to come straight out of a miniature painter’s hand. On one of the wool-pile rugs, however, the number of beasts swells while the landscape is relatively muted and its border is of an older compartment style.

An additional number of small rugs are of the more familiar and frankly more commercial 17th-century Esfahan all-over type (without figural motifs) that are more regularly seen in the trade, in museums and in Renaissance painting. Seeing them in Iran brings out a further nuance of their eponymous ‘Shah Abbas’ name, after the king who played such a role in promoting Persian carpets in the global economy. ‘Shah Abbas’ remains the Persian term for any floral workshop rug whose design is neither directional nor centralised, but seeing the pioneer surrounded by all the younger pretenders is quite a sight.

A further set of Safavid weavings that is coherent but perhaps less familiar to many museum-goers is the group of silk kilims said to be attributable to Kashan in the second half of the 16th century. They are of the type recently showcased at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which are relatively more elaborate in style and artistic effort. Two such kilims were on show at the CMI, both on loan from the National Museum of Iran, which recently reopened its Islamic section after years of refurbishment. I also visited that museum and saw that they also have two additional silk kilims of type.

Prayer rug bearing the traditional prayer chant subhan rabbi al A’ala and more personal prayers (rather than Qur’anic verses), Tabriz or Khorasan, 16th century. 1.02 x 1.45 m (3’4″ x 4’9″). National Museum of Iran, inv. 3405

All four currently in Tehran have a marked absence of figural motifs, in stark contrast to the more famous members of the group. They are rather long and narrow in format and almost give an impression of being the flatweave variant to the ‘Polonaise’ pile rugs. They rely on a more limited colour palette and, while woven of silk, have more stylised or simple vegetal motifs that are larger in scale and allow for more open spaces. They convey a sensation of being a notch below the more animated or dynamic silk kilims with figural elements and more sophisticated design. As with the ‘Polonaise’ rugs, I suspect these silk kilims may have been intended for the export market. All four of them have substantial moth damage in sections of particular colours.

The display included a number of larger carpets with generally 17th-century Esfahan or Khorasan provenance. The CMI’s large ‘Sanguszko’ retained its pride of place in the centre of the gallery where it has been for many years now. In fact, it is the only Safavid-period carpet that was on display rather than in storage.

A particularly interesting sight was a richly-ornamented carpet with a rich trellis field with lotus palmettes and cloud collar forms surrounded by an eye-catching compartmented border. It was candidly attributed to 16th-century Herat, although a broader Khorasan origin is quite credible. Vying for the title of the largest Safavid piece on display were two gigantic red-ground carpets, each approximately eight metres in length. One seems to be a 17th-century Khorasani carpet; its all-over aesthetic suggests it to be a forerunner of the famous Herati leaf style. The other is incomplete, with roughly two-thirds of it present. It has a central medallion design with a smart compartment border and some attractive green tones.

Apart from the familiar clusters of Safavid carpets and kilims, a few specific exhibits at the CMI stood out in their own right for being somewhat distinctive and rather more difficult to categorise. A striking small prayer rug of green hue was borrowed from the National Museum of Iran. The lower half of the field is rich with scrolling vinery and split-leaf spirals that rather abruptly stop at the neck of the mihrab halfway up the rug. Above this, the field is plain green, apart from a floating pendant bearing the traditional prayer chant subhan rabbi al A’ala. The silhouette of the mihrab is thick and contains somewhat personal prayers to God rather than Qur’anic verses.

The borders too carry a lengthy inscription in the Safavid style, leaving only the bottom border and the lower sections of the lateral borders free from any words. This inscription is a prayer to God to bless the Prophet Muhammad and the Twelve Imams, a very Safavid ethos. The inner border is the only place where the Qur’an is cited, in this case with Ayat al-Korsi or the Throne Verse. The curators attribute this object to Tabriz once more on account of its symmetrical knotting structure; they posit that it is 17th century. Interestingly, the National Museum has two further prayer rugs on display that are of a more recognisable aesthetic.

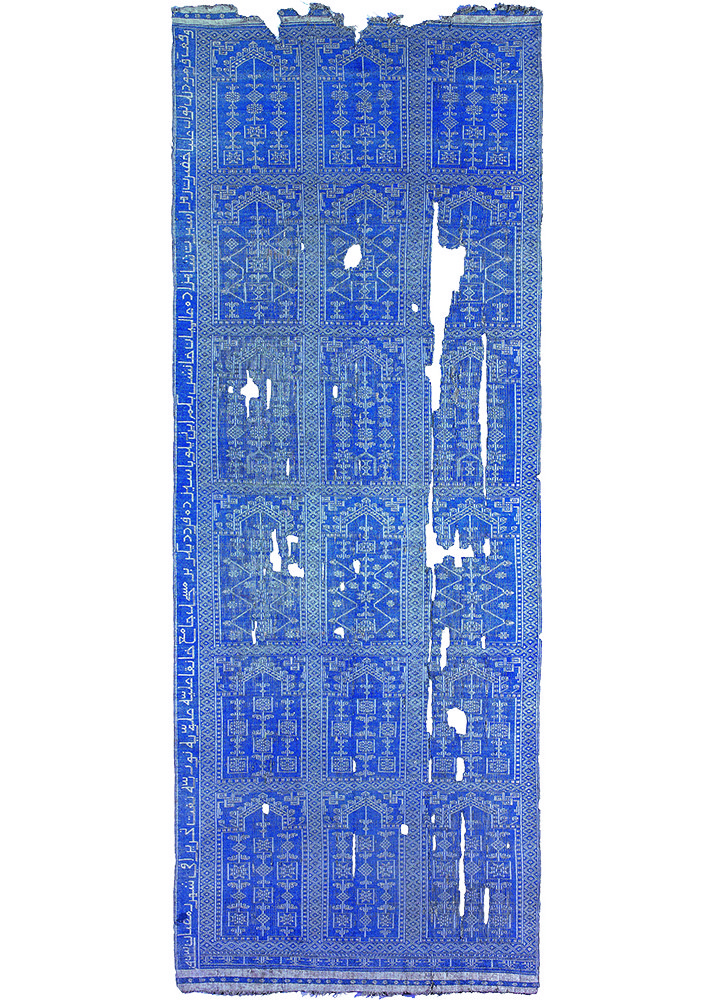

Zilu multiple niche prayer mat with inscription, dated 963 AH (1556 CE) making it the oldest dated ‘rug’ in Iran. 1.67 x 4.40 m (5′ 6″ x 14′ 5″). Carpet Museum of Iran, inv. 976

Two other pile-less weavings are worthy of mention. One of them, a singularly large bichromatic zilu prayer mat, bears the honour of being the oldest datable object in the museum’s collections and indeed the oldest dated ‘rug’ in Iran at the moment. Common jargon in carpet literature would append the titular name ‘saf’ (or ‘saph’) to it, denoting the multiplicity of mihrab prayer niches. It has six rows bearing three mihrabs each. A lengthy inscription meanders along its left border and states:

This zilu and thirteen other items [probably more zilus] were donated by Khanesh Begom [Shah Tahmasb’s sister, married to a descendant of one of Shah Nematollah’s Valis—a 14th-century Sufi, who died in 1620], Princess (Shahzadeh) of the people, High Regent of Hazrat-e Zahra [Muhammad’s daughter], to Masjed Jame’ Khaneghah [a religious place for Sufi gatherings] in Taft [a small town northeast of Yazd]. Ramadan of the year 963 Hijri [1556 AD].

The Tehran curators indicate this object was woven in the vicinity of Yazd in east-central Persia, possibly in the town of Meybod, where zilu weaving continues to the present day. Finally, a glass cabinet contained what seemed to be a pristinely-preserved namad or felt, also of prayer design. It is quite a singular object, with the shahada emblazoned atop the mihrab and the borders containing prayers in the honour of the Prophet Muhammad and the Twelve Imams in the exact same vein as the green-ground prayer rug.

European travel literature of the 16th to the 19th centuries indicates the ubiquity of felts in Persian settings: palaces, domestic interiors, bazaars, etc. Nonetheless, very few specimens survive for various reasons. On the one hand, they were quite prone to moth and water damage. On the other, they were rarely considered precious enough to preserve and maintain, being so simple in execution.

Felts appear with a high degree of regularity in Qajar paintings (thick, bulky and massive) but they are a familiar element in Safavid miniature painting too. (See Hadi Maktabi, ‘Under the Peacock Throne: Carpets, Felts, and Silks in Persian Painting’, Muqarnas XXVI, pp.317–47). The type of felt we see in Safavid, Afsharid and Zand painting was of a far finer handle and a higher degree of aesthetic complexity, exclusively appearing in scenes depicting princes and rich dandies. It is thus a welcome surprise to discover that one such piece has survived for so long.

‘Polonaise’ rug, woven in the royal ateliers established by Shah Abbas, Esfahan, central Persia, ca. 1600-1650. Silk pile with metal thread brocading, 1.41 x 2.06 m (4’ 8” x 6’ 9”). Carpet Museum of Iran, inv. 151

The CMI has done well to share its Safavid treasures with the public for the first time. It is to be hoped that this will be the first of many specialised displays that will showcase the CMI’s very rich and extensive holdings, the majority of which have never been published.

What struck me across the week I spent in Tehran was how stark a conceptual contrast there was between the Safavid carpets on display and the numerous Qajar/Pahlavi-era ones that remained hanging on the perimeter. The show in Tehran brought much of the best of both antecedent and subsequent periods together in sight for perhaps the first time in a museum setting. Having spent most of the past two decades studying the post-Safavid and pre-revival carpets of the 18th and early 19th centuries, I found it an eye-opener to see objects from the same weaving centre that lay either side of that chronological divide.

Looking at the rugs of, say, Kerman, Kashan or Esfahan, the viewer is startled to see how different the Safavid and late Qajar or Pahlavi-era traditions are. What links a 17th-century ‘vase’ carpet to a ‘Mashahir’ Kerman, or indeed a ‘Polonaise’ to a Seirafian? Obviously, two to three centuries separate them in time; but the point is that the shifts in style, execution, aesthetic, and draughtsmanship were more a case of revolution than evolution. Shah Abbas would not have recognised the later ones at all.

Comments [0] Sign in to comment