‘The art of kilims’

The current exhibition at the George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum in Washington DC, ‘A Nomad’s Art: Kilims of Anatolia’ on view until 23 December, features 18th- and 19th-century Anatolian kilims entrusted to the museum by Murad Megalli’s family. HALI 197 features an introduction to the collection, with abridged extracts from A Nomad’s Art—the catalogue produced by HALI. The following is extracted from ‘The art of kilims’ article in HALI 197 by the exhibition curator and catalogue co-author Sumru Belger Krody:

‘Murad Megalli was a long-time friend of The Textile Museum in Washington. A successful executive at J.P. Morgan, respected collector of Central Asian ikats and Anatolian kilims, and former Textile Museum board member, he died in a tragic accident during a business trip to Northern Iraq in 2011. His estate named the museum as steward of a large portion of his kilim collection (where they join his ikats), the other part being entrusted to The Koç Foundation in Istanbul.

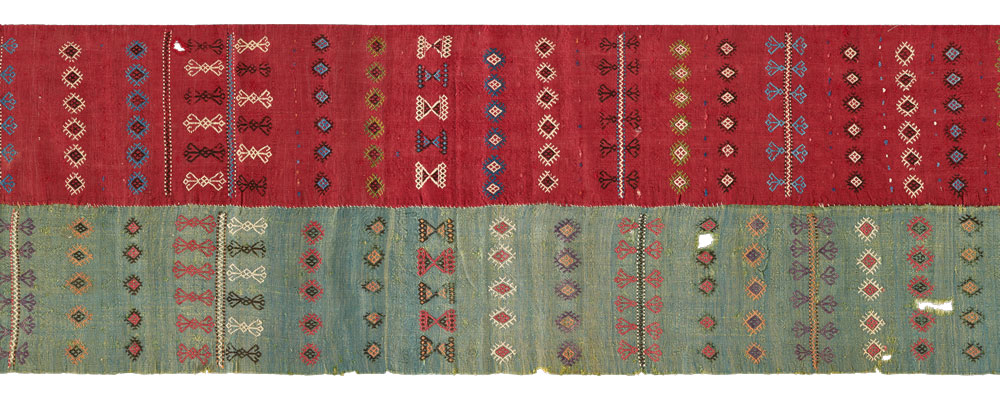

Kilim is a general name given in Anatolia and its surrounding areas in West Asia to a group of sturdy utilitarian textiles woven in slit tapestry-weave technique. These are multifaceted objects and have played an important role in the artistic history of Anatolia. The highly-developed designs and fine execution seen on the 18th and 19th century kilims in the Megalli Collection suggest that the tradition is long-established.

Colour, composition, and scale make Anatolian kilims captivating to today’s viewers, but these textiles hold importance far beyond their contemporary visual impact. Most importantly, they are the only surviving, tangible evidence of their makers’ nomadic lifestyle. This is a remarkable legacy, given that their female creators did not know how to read or write, and lived in a patriarchal society in which women generally had no external voice. It is ironic that despite these constraints, it is their work, and no other lasting cultural manifestation, that gives testament to their centuries-long way of life.

Like all tapestry-woven textiles, Anatolian kilims have a weft-faced plain weave structure, but the design is built up of small areas of solid colour, each woven with its individual weft yarn. Between two adjacent colour areas the respective wefts never interlock or intermingle but turn back using adjacent warps. The result is a vertical slit. This had enormous impact on kilim design; the ordering of colour areas to avoid excessively long slits resulted in characteristic patterns built on diamonds, triangles, and lozenges. Slit-tapestry is inherently limiting for creating curvilinear forms unless the weaver has the necessary equipment, time, experience, know-how—and most importantly, very fine yarns. In creating designs, Anatolian kilim weavers seem to have accepted the technique’s natural limitations instead of working against them.

Each Anatolian kilim demonstrates the complicated interactions between the creative energies of a weaver, her community, and her exposure to the political, economic, and social environment in which she lived. These kilims can be seen as remarkable examples of the power of these nomadic women to create an artistic tradition that endured for centuries and still resonates with contemporary audiences.’

Comments [0] Sign in to comment