Elegant Structure: The Pattern of a Collection

‘Wild man’ tapestry fragment depicting a bearded man ploughing a field, Basel, mid 15th century. Ex Robert von Hirsch Collection; Cotsen Collection

In a lifetime of collecting, Lloyd Cotsen refined his own interests while expanding opportunities for artists and scholars. Throughout, he maintained a fascination for the way objects are constructed—and understood how a mere fragment can reveal the secrets of a complete textile. Lyssa C. Stapleton, curator of the Cotsen Collection, gives an overview of the man and his collections.

Loyd Cotsen (1929–2017) drew immense enjoyment from his collections but intended for each to accomplish something positive. His collecting was fundamentally philanthropic and he wished for each object to contribute to scholarship and promote underappreciated art forms. To the general public, he was best known as the marketing genius behind the Neutrogena brand of skin-care products, but his creativity was outwardly expressed through his art collections. Cotsen was a cultural scholar, a skilled photographer, and an admirer of artistic expression in all its forms. He explored the world head-on; a man dedicated to living life on his own broad terms.

Cotsen graduated from Princeton University in 1950 with a degree in history. He served in the navy during the Korean War and, during that time, cultivated a life-long interest in Japanese art and culture, as well as Chinese art and archaeology. He acquired some of his first works of fine art while in Asia, including painted scrolls, sculpture, ancient bronzes and Japanese prints. After his discharge from the navy in 1953, he married JoAnne Stolaroff (1928–1979) and in 1954 commenced graduate studies in architecture at Princeton. The same year, he accepted a position as field architect at the important Mycenaean Bronze Age site of Lerna, on the east coast of the Peloponnese, and in 1955–56 was a fellow of the American School of Classical Studies in Athens. Cotsen and his new bride spent that year and several summers travelling, studying and excavating in Greece.

Bedcover or hanging fragment (detail), Skyros, Greece, 17th century. 41.3 x 47 cm (1′ 4″ x 1′ 6″). Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection, T-0744

The Cotsens’ Los Angeles home was filled with ethnographic, archaeological and contemporary objects from all over the world. JoAnne was a graduate of Parsons School of Design, where she had studied clothing design. Her interests in fabric, weaving and ethnographic costume influenced Lloyd’s early collecting. While CEO of the Neutrogena Corporation, he built a world-class collection of international folk art, which included sculpture and basketry but leaned heavily toward ethnic costumes and textiles. Much of that material was donated to the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe (MOIFA) in 1995.

Naxos cushion cover (detail), Greece, 17th/18th century. Silk embroidery on linen; 38 x 71.1 cm (1′ 3″ x 2′ 4″). Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection, T-1155

Thereafter Cotsen modified his collecting parameters, establishing scholarly and philanthropic goals. He continued to focus on lesser-known genres of art and began to assemble study collections as a means of encouraging the continuation of indigenous crafts and to support scholarly research.

He collected a wide variety of three-dimensional woven objects including North American Indian baskets, early American folk baskets, and baskets made by the ancient Tiwanaku culture of the southern Andes. Sometime in the 1960s, the Cotsens purchased their first Japanese bamboo basket while on a trip to San Francisco. Cotsen recalled that its appeal was in its imperfection; the basket is misshapen with wide, irregular strips of bamboo woven on the horizontal and a narrow, twisted handle that is out of proportion with its bulging body. Over forty years he acquired more than 1,000 Japanese bamboo baskets, over 900 of which were donated to the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco in 2005. The contemporary basket collection, comprising just under 150 items, was donated to the Racine Art Museum in 2007.

In 2000, he established the biennial Cotsen Bamboo Prize, an award for young Japanese bamboo artists. Its purpose was to provide financial support so that artists could focus on their work, but also introduce the art of Japanese bamboo basketry to a wider, international audience, providing a market for basket makers. In 2006, he created the Cotsen Foundation for Academic Research, a non-profit, grant-giving organisation supporting individual scholars and museums. In travels with his second wife, Margit Cotsen, he continued to acquire different materials, but he restricted his acquisitions to predetermined categories: primarily textiles and basketry. In 2005, he and Margit began to assemble a stunning collection of contemporary Japanese ceramics. This was to be his final collection.

Two of Cotsen’s collections are study collections. By giving them this designation, he specified that their primary purpose is as a resource for scholars and institutions. The first of these is the Chinese Bronze Mirror Study Collection, donated to the Shanghai Museum in 2012. The second is the Textile Traces Study Collection, which Cotsen began assembling in 1997 with his then textile curator, Mary Hunt Kahlenberg, and myself. Comprising some 4,500 pieces from all regions and periods, it is his most comprehensive collection and pieces from it have featured in dozens of exhibitions, publications, and scholarly studies.

Irland (detail), by Maria Likarz-Strauss for the Wiener Werkstätte, 1903-1932. Printed linen and silk. Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection, T-0193-142 and T-0193.143

One of Cotsen’s most unusual characteristics as a collector was an all-encompassing fascination with weaving and woven structures. He understood that a maker’s skill is captured in the weave itself and that just a small fragment can tell the story of its structure, surface treatment, fibre and the dye techniques used to create it. He realised that a small sample could convey almost all the information that a complete piece could. His perception of the utility of small and fragmentary items led him to develop the Textile Traces Study Collection.

Tapa cloth fragment with a geometric pattern pigmented in black, Hawaii or the Futuna Islands, late 19th to early 20th century. 25 x 29 cm (10″ x 1′ 0″). Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection, T-2922z

Cotsen had already learned that large items present mounting, storage—his collections still include many textiles too large for Textile Traces—and accessibility challenges. The small size of objects in Textile Traces facilitates easy handling and storage; they are mounted in either 24 x 14-inch or 14 x 14-inch archival folios. The small-format folios make the collection a more accessible resource for textile scholars, as does their organisation in storage boxes by region and date.

Tapestry fragment depicting St James Major, Netherlands, ca. 1500. Silk and wool; 98.5 x 51 cm (3′ 2″ x 1′ 8″). Cotsen Collection, NT-0826

His journey as a collector was guided by his acute ability to perceive light, colour and space. Kahlenberg frequently lobbied for acquisitions that expanded poorly-represented areas of the collection. Cotsen, however, was unabashedly attracted to bold designs and intricately constructed objects. His interest was often piqued by how an object was originally used and he most often arranged things for display according to patterns and textures rather than chronology or place of origin. In his private gallery and research space in Los Angeles, Bunraku puppets gaze at pre-Columbian qipus and a carved wooden Lakshmi statuette dances on top of a Sicilian peddler’s cart.

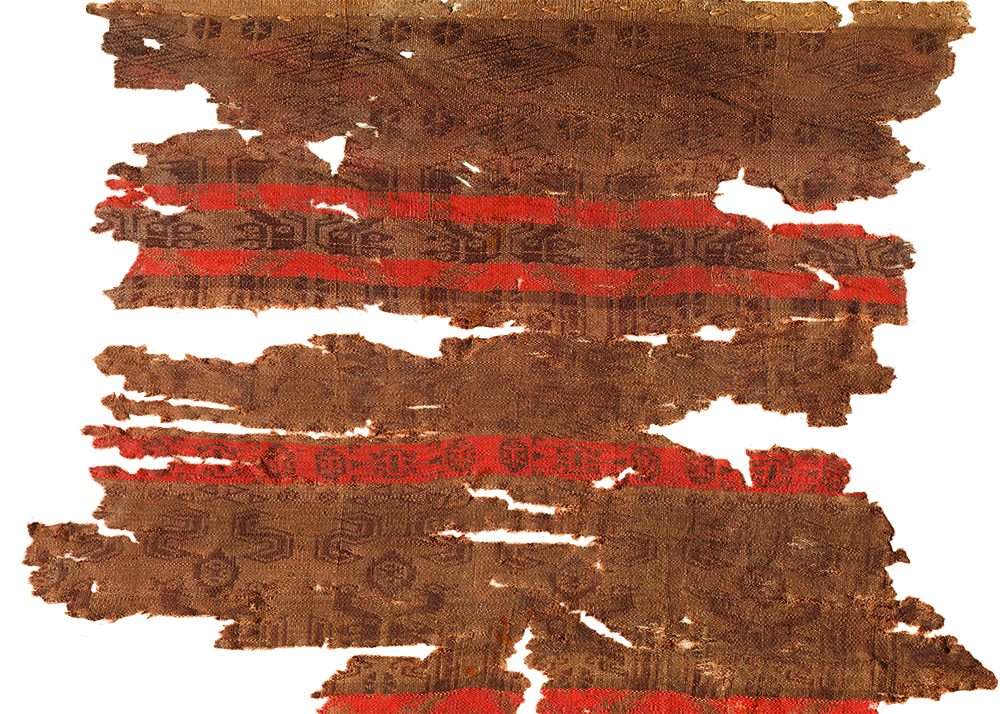

Textile fragment with dragons, phoenixes, and wild beasts, China, Warring States period, 308-207 BCE. Silk, warp-faced compound plain weave. Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection, T-0327c-d

Items acquired were often related to cultures and practices he observed or mirrored his own experiences. During his time in Japan as a naval officer, Cotsen developed a life-long admiration for Japanese traditional crafts. The Textile Traces collection holds more than 700 pieces from Japan, the earliest dating to the Momoyama period (1573–1615); the most recent is just a few years old. A fragment from a woman’s garment dating to the 19th-century Ryukyu Kingdom (now Okinawa) is dyed on both the interior and exterior using a stencil-resist bingata technique and is woven in ramie, or possibly banana, fibre. The bright, multicoloured pattern features cranes, bamboo and cherry blossoms. In contrast to the organic tones and fibres used in the bingata fragment is a contemporary textile made with polyester, nylon monofilament, and aluminium-plated polyester micro slit film double weave, designed by the trailblazing designer Junichi Arai (1932–2017). Arai and Cotsen met in 2003, and having heard about the Textile Traces collection, Arai invited Cotsen to his home to select examples of his work.

Kimono fragment, Okinawa, Japan, 19th century. Banana fibre, plain weave, stencil and resist dyed (bingata). Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection

Cotsen’s interest in Chinese archaeology began when he was a child perusing his parents’ books on Chinese art. At Princeton, he enrolled in an Asian art history course with George Rowley and then repeated it because he found the material fascinating. Although he never excavated in China, Chinese textiles form one of the cornerstones of the Textile Traces collection. Cotsen focused on both the warp-faced silk textiles produced by early Chinese dynasties and the woven wool garments created by the nomadic groups of the Tarim Basin (in modern Xinjiang province).

Garment fragment (detail) with boys carrying branches with bird cages and wearing fur-lined robes and gloves while riding goats, Ming dynasty, 1368-1644. Silk brocade with metallic thread. Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection, T-0088

Cotsen’s first Chinese bronze mirrors were also acquired in the 1950s while he was serving in Asia. His enduring fascination with these objects was in part due to similarities between the designs cast on mirrors and those woven into textiles. Included in the corpus are cosmological and mythical emblems like dragons, phoenixes, tigers, birds, and taotie masks, as well as more stylised representations of thunder, clouds, and the five sacred mountains. These emblems conveyed auspicious and protective powers. They are arranged and read differently according to the shape of the final object and the material it is made from.

Early mirrors, particularly those of the Warring States period, incorporated geometric designs into a background pattern. Similar planning is required to design both textiles and decorated bronze objects. For textiles, a pattern repeat is required and in the Chinese aesthetic, particularly in the Bronze Age, bronze vessels were decorated with repeating registers of common motifs. A Warring States mirror from the Cotsen Collection with lozenges and phoenixes is now in the Shanghai Museum. Four raised lozenges are part of the foreground design, and the fine ground pattern is worked in a complex, interlinking ‘key’ pattern that symbolises thunder.

Garment fragment (detail) with beribboned winged horses (detail), Sasanian Persia, 338-596 CE. Silk samite. Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection, T-0952

The complex pattern of a textile fragment with dragons, phoenixes and wild beasts includes lozenges similar to those seen on the mirror, as well as confronting birds and phoenix, the sun and stars, pairs of beasts, and dragons. The bold red, as well as the light and dark brown, were certainly pigmented with cinnabar. This rare mineral was stuck to the silk using an unknown emulsion, which is probably responsible for the longevity of the colour. This fragment is one of a group of five compound warp-faced tabby (plain-weave) silk fragments dating to the Warring States period (308–207 BCE) in the Textile Traces Study Collection. Textiles of this weave, known as jin, are typical of the Warring States period, and the technique requires sophisticated weaving skills and a complex loom.

Warp-faced weaves and the looms required to produce them are a defining characteristic of early Chinese weaving. The earliest weft-faced fabrics appear in the Xinjiang region during the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). Known as taquété, these fabrics are woven in a weft-faced compound tabby. The manufacture of weft-faced textiles necessitated different looms and is indicative of the role of the Silk Road in the transmission of ideas, goods, and technology.

Textile fragment, China, Tang dynasty, 8th–9th century CE. Warp-faced compound silk. Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection, T-1803b

Cotsen often wanted easy access to his favourite things, so he created a pair of boxes for them. Included there was a Han-dynasty (120 BCE–90 CE) mitt or glove, decorated with swirling, stylised cloud motifs in black, blue, orange and gold on an off-white ground. The tabby-woven ground fabric is not notable, and it is only with a close examination that the incredibly fine pattern can be identified as chain stitch embroidery, rather than a painted design. Chainstitch embroideries were popular in the Han dynasty and many examples are included in the collection. The fibres used in the ground cloth do not appear to have any spin, which is not unusual for early Chinese textiles. The fibres used for the embroidery have only a very slight S-spin. Typically, the silk thread used in Han-dynasty embroidery has a lower thread count and is wider in diameter than the fibre used to embroider the mitt. The average thread count for this embroidery is 23 stitches per centimetre. While we know how this object was constructed and embellished, it still holds one mystery: how an embroidery of this incredible delicacy was executed without leaving visible holes in the fine, tabby-weave ground fabric.

Part of Cotsen’s fascination with Chinese textiles was linked to his interest in the social and cultural impact of Silk Road commerce. The transmission of technology, raw materials, artisans, and even aesthetic sensibilities via the Silk Road are reflected in the collection. As a meeting place for many cultures, Cotsen found the Xinjiang region particularly intriguing. He counted Elizabeth Wayland Barber among his close associates and was a great admirer of her books on early textiles and familiar with her work on the mummies of Urumchi.

The Tang dynasty was a period of accelerated contact and trade between China and cultures to the west via the Silk Road. A fragment dating to the Ilkhanid period of the Mongol empire in the collection has a distinctly Persian motif. This textile was undoubtedly made in China for export. Popular motifs also came from even further east, as evidenced by Buddhist-influenced, mandala-like floral component shown in a textile fragment. This beautiful silk from the Tang dynasty was manufactured in China for the Central Asian market.

Bow cover, western China, Northern Dynasties, 386-581 CE. Silk chain-stitch embroidery; 73.7 x 25 cm (2′ 5″ x 10″). The Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection, T-2735b

During the Tang dynasty, the Sogdian people, merchants travelling between what is now Tajikistan and Uzbekistan and the court of imperial China, played an important role in the Silk Road trade—they even held official roles in the imperial court. Textiles with Sogdian-style patterns and possible manufacture are often found in China, and questions about the genesis of common design patterns and weave techniques are of particular interest to scholars. One of the more typical decorative elements is the pearl roundel, which most often surrounds an animal or animals. Animals and roundels were popular both in China and the Sasanian empire (205–651 CE), and later in Sogdian designs. A Central Asian bag used to contain and carry a bow is constructed from multiple silk fragments; the bow case has an embroidered central panel with a pattern of upturned crescents within a grid of pearls. The crescent pattern was also a popular motif in China, Central Asia and the Sasanian empire. The edges are finished with a Northern-Dynasties-period textile with a pattern of pairs of camels, elephants, lions, and important personages seated under a canopy or building.

Fragment with a pattern of griffins or winged elephants, India, Sultanate period, late 12th to mid 15th century. Silk samite (weft-face compound twill weave). Cotsen Textile Traces Collection, T-0113

Sasania is known for the production of silk samite (weft-faced compound twill weave), a technique that was later used by Sogdian weavers. These textiles were traded as luxury goods along the Silk Road, commerce that continued throughout the Byzantine and Islamic periods and into the Middle Ages. The design of a fragment of a Sasanian silk samite robe, dated to 338 and 596 CE, and most likely once the property of a nobleman, shows two winged steeds facing in the lower register with two more, addorsed, in the upper. Below the feet of the Pegasus is a tab and floral pattern perhaps representing mountains. The Pegasus of Greek myth was a popular Assyrian, Sasanian, and Persian motif. The winged horses are decorated with ribbons tied around their forelegs and wear pearled collars tied with flying ribbon. Ribbons, particularly those with a flaring, tassel-like end, are a common decorative element in depictions of Sasanian royalty and can be seen in royal hunting scenes depicted on silver plates and in the post-Achaemenid graffiti at Persepolis.

Among the Chinese holdings of Textile Traces are very fine pieces from later dynasties such as the embroidery illustrated on the cover of HALI 194. This Yuan (Mongol)- or Ming-dynasty embroidery with human figures, a tiger, floral motifs, and architectural elements is worked on twill damask, the border is made of flat gold. Also from the Yuan dynasty is one of eight related fragments depicting immortals bearing gifts. The heavy laid and couched embroidery used to create the figural elements is unusual in that it completely covers the foundation fabric.

Unfinished purse, England, 17th century. Silk embroidery on silk satin with silver sequins and silver wrapped thread; 27 x 11.4 cm (11″ x 5″). Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection, T-0129

The Textile Traces Study Collection includes significant, if not large, holdings of early Chinese material; but it is the smallest, most damaged pieces that betray Cotsen’s somewhat whimsical attraction to glimpses of patterns. Cotsen was as delighted by men riding goats as he was by a fragment of silk samite with a griffin or stylized, winged elephant from India. He was endlessly charmed and intrigued by the fine and elaborate garments of the Elizabethan era, among them an unfinished purse with finely-worked portraits of a girl and boy.

Cotsen regularly attended and supported conferences and other scholarly projects related to weaving and textile research. His strong admiration for weavers and textile design encouraged artists like Junichi Arai, and others, to ensure that their work found a place in the Textile Traces Study Collection. He further supported contemporary artists by commissioning more than 40 small-scale works for Textile Traces. The unique composition of the collection led to the acquisition of other groups of small fragments.

Section from a dalmatic vestment, Ottoman Turkey, 16th century. Silk lampas weave with silver gilt thread; 26 x 26.5 cm (10″ square) . The Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection, T-0232. Formerly Dikran Kelekian, New York

One such acquisition was of Late Antique/Byzantine fragments from Egypt, from the site of Antinopolis on the east bank of the Nile. The city was named for the deceased lover of the Emperor Hadrian, Antinous, and was excavated between 1896 and 1908 by Albert Gayet. As was common on early 19th-century excavations, many small finds that were not considered to be of scholarly import or interest were collected by members of the project. One such collection was compiled by the site draughtsman, Jules Paul Gérard. The group of textile fragments gathered by Gérard was carefully kept and curated by his family until his grandson decided that there could be no more appropriate recipient than a former excavation draughtsman-turned-textile-collector. These fragments form the core of the Late Antique group in the Textile Traces Study Collection.

Border fragment of an armorial carpet, Spain, Letur or Alcaraz, second quarter 15th century. Wool with knotted and cut pile; 24 x 47 cm (9″ x 1′ 6″). Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection, T-2718

Egyptian weavers were occasionally influenced by designs on imported fabric from the east: imitations of Sasanian, Persian and Bactrian silks are sometimes found, such as an Egyptian interpretation of a royal hunting party of the type seen in Sasanian media. Two riders on horseback carrying lotus stalks stand within a roundel. This piece was probably made to be applied to a tunic, but the intact selvedge may indicate it was never used. While the eastern influence is clear, this textile shows that patterns that can be rendered in a silk compound weave cannot be perfectly reproduced using tapestry-woven linen and wool.

More typical for textiles woven by Egyptian Christians are depictions of Christian saints and another religious iconography; but also found are designs that reflect the influence of Roman fashion and funerary ritual. A fragment of a shawl woven with a linen warp and wool weft is inscribed ‘Jesus Christ bless Moses your servant’. The pattern includes a series of connected lozenges or roundels containing paired rabbits or abstract patterns. The lozenges are interspersed with sea monsters, fish and birds.

Four-cornered hat, Peru or Bolivian Altiplano, Tiwanaku culture, 7th-9th century ce. Camelid fibre with larkshead knotting. Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection, T-0047

An architect by training, Cotsen perceived the dimensionality of textiles. He grasped the technical commonality between baskets and textiles, seeing them as correlates rather than flat versus three-dimensional. Cotsen collected nearly twenty small baskets from the Bolivian Altiplano, some dating to the Tiwanaku period, and some that are later. All but one are woven from dyed grasses. It is a coiled basket, as are the others, but woven with dyed camelid fibre, making it somewhat less rigid than other baskets of this type. Camelid fibre is also used to create the complete four-cornered hat above. Somewhat like a coiled basket, the Tiwanaku-style hat is constructed from a central starting place, in this case, its crown. Using a needle, larkspur knots are looped around a foundation element, which also allows for colour changes. Raised patterns are created by altering the direction of the knot. The design is primarily geometric, with confronting, anthropomorphic heads.

Cotsen’s group of pre-Columbian fragments is nearly comprehensive: from painted Chavin fragments to a complete, late Incan mantle. Collections from Japan, China, and 16th- to 18th-century Europe are also strong. Other regions and periods, such as Late Antique textiles, African, Oceanic, and Middle Eastern materials are represented by fewer but excellent examples. These were lacunae of interest for Cotsen, whose broad understanding of textile history prompted a focus on specific culture groups or time periods with unique weaving traditions. These include a fragment of a 15th-century Spanish knotted pile carpet and a small but dazzling group of Ottoman textiles. Ottoman silk textiles are some of the most elegant and refined in the Islamic world. Made in Bursa is a lampas weave (see above). It has a brocade ground with a silver-gilt wrapped supplementary weft.

In stark contrast to the elaborate fabrics of the Ottoman Empire, Cotsen’s interest was perhaps even more piqued by the political role that could be played by textiles. Propaganda textiles in the collection include a few Japanese children’s kimonos from Second-World-War Japan and a few hundred textile samples and designs that comprise the Soviet propaganda collection.

One of eight fragments depicting immortals (hsien) bearing gifts, China, Yuan (Mongol) dynasty, 14th century. Heavy silk laid and couched embroidery. The Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection, T-0139c

The textile resources that Cotsen assembled when building the Textile Traces Collection were influenced by his personal interests but were also a concerted effort to include any relevant resource. In addition to the fragments themselves, the collection also includes nearly 100 sample books, pattern books, and dye chemistry texts from Japan, Europe, North America, and the former Soviet Union. Cotsen viewed these resources as collections within the collection. Sample books embody the concept of Textile Traces. In this form, as in the Textile Traces Study Collection, small fragments are the focus. Their modest size draws you near, demanding close examination. Fragments, as Cotsen conceived them, are a primary source, a stepping-off place for interdisciplinary research; a thread to be followed to a wider world of information.

Comments [0] Sign in to comment