Anatomy of an Object: A Flemish Tapestry

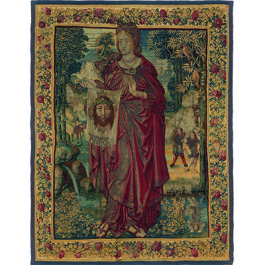

Saint Veronica tapestry, Brussels, circa 1520. Wool, silk and silver-gilt thread; 1.30 x 1.73 m (4′ 3″ x 5′ 8″). Value at time of manufacture = 52 cows. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, bequest of George Blumenthal, 1941, 41.190.80

‘Relative Values: The Cost of Art in the Northern Renaissance’ currently showing at The Met (open until 23 June 2019) uses the currency of cows to illustrate the expense of tapestries at the time of their manufacture. Rachel Meek discusses the exhibition’s concept and sole tapestry with curator Elizabeth Cleland.

Tapestries were the impetus for Elizabeth Cleland’s current show of around sixty objects, ‘Relative Values’, at The Met. The curator of the museum’s splendid Pieter Coecke van Aelst tapestry exhibition (2014-2015) explains: ‘For a long time we have been trying to encourage the understanding that when tapestries were new, in the 15th and 16th centuries, they could be astronomically expensive and, as a whole, the medium was much more highly valued by its original audience. A painting of the Virgin and Child owned by the Habsburg King Philip II, for example, was valued at less than a tenth of the price of a Flemish tapestry of similar size and subject matter. I thought it would be illuminating to actually prove this by returning to prices and valuations mentioned in a plethora of 16th-century documents for all kinds of art objects, and devote an exhibition to exploring this hierarchy of relative worth between different artistic media.’

The most useful source in the creation of the exhibition’s comparative price index was King Philip’s tapestry inventory which lists valuations per el (unit of measurement). Comparable works from Brussels with a similarly high warp count, copious use of metal-wrapped threads, and virtuoso weaving techniques, acquired from the 1540s-early 1560s, are valued at 30 Spanish ducats per el. At this rate, the present tapestry’s value would equal 151 ducats, roughly equivalent to 9,100 grams of silver.

Cleland took this further: ‘I felt that citing silver weight, though useful, was still not terribly informative for our visitors. Knowing that for most households across northern Europe circa 1550, a milking cow was considered a great asset and that their cost remained relatively stable, I used cows as my ‘currency’, enabling visitors to better understand the ‘buying power’ of each object when new, so that they can be readily compared.’ The approximate price of a milking cow was 175 grams of silver, equivalent to 35 days’ pay for a skilled craftsman working in London or Antwerp; 59 days’ pay for an unskilled labourer working in London or Antwerp; 27 bushels of wheat in Ghent, Paris, or Vienna; or 5,350 loaves of rye bread in Brussels. According to this system, this tapestry is worth 52 cows, whereas a Quentin Metsys-attributed painting in the show is equal to only 5 cows.’

Upon the death of George Blumenthal in 1941, the Saint Veronica tapestry was bequeathed to The Met, along with the rest of his extensive art collection. In 1919, his first wife Florence paid the Parisian dealer René Gimpel a sum of $80,000 for the piece. At that time in England, a ‘second quality short-horn’ was worth approximately 800 shillings (£40) and a Gloucester-breed cow fetched up to £58.

Today, the relative values of both tapestries and cows in comparison to contemporary art have altered dramatically, but the details in the gallery below highlight why this work of art was so costly at the time of its creation and why it is worthy of appreciation in its first showing at The Met.

Anatomy of an object

6 images

Today, the relative values of both tapestries and cows in comparison to contemporary art have altered dramatically, but the details in this gallery highlight why this work of art was so costly at the time of its creation and why it is worthy of appreciation in its first showing at The Met.

- Raw materials contributed greatly to the overall expense: imported wool, silk and high-quality dye-stuffs achieved rich colour and precious metal-wrapped threads—at this date literally narrow strips of beaten silver and gilded silver wrapped around a silk thread core (apparent in the liberal highlighting of Veronica’s gown)—were used.

- Raw materials contributed greatly to the overall expense: imported wool, silk and high-quality dye-stuffs achieved rich colour and precious metal-wrapped threads—at this date literally narrow strips of beaten silver and gilded silver wrapped around a silk thread core (apparent in the liberal highlighting of Veronica’s gown)—were used.

- The story of Saint Veronica wiping Christ’s face with her veil as he carried the cross, then finding a ‘vera icon’ (true image) imprinted upon it, was popularised by the Passion Plays, which were often performed in German in the 16th century. The German word ‘Forneca’ is presumed to relate to the phrase ‘vera icon’ rather than to the saint. The skill of the most accomplished Flemish weavers is evident in the delicate pleated corners of the veil held in Veronica’s fingers, where slits achieve a three-dimensional effect, as well as in the subtle nuances of shading and tone on the face of Christ, achieved by hatching colours together.

- Fine details are apparent throughout the design: see for example a reflection in a pool of water, strawberry seeds and the saint’s toes.

- Fine details are apparent throughout the design: see for example a reflection in a pool of water, strawberry seeds and the saint’s toes.

- Illusionism is employed on three spatial planes: the landscape piercing back beyond the wall on which the tapestry would hang; the decorative frame occupying the same plane as the wall; and Veronica herself, seeming to step forward out of the tapestry, her headdress (a symbol of her Syrian nationality) represented in front of the border.

Comments [0] Sign in to comment