Striking Simplicity

In HALI 204, Gebhart Blazek and Alexandra Sachs celebrate the distinctive qualities of Moroccan flatweaves—everyday items that exceed expectation with their evocative, painterly designs.

In recent decades Moroccan kilims have attracted scant attention by comparison with pile carpets and ceremonial textiles. This may be due to the fact that their appearance is influenced to an unusually high degree by the possibilities and limitations offered by the complex weaving techniques used in their production. But some, comparatively rare, kilims follow similar design principles to certain groups of knotted carpets; their visual language is similar to that of tapestry, drawing on painterly effects and strong and bold graphics.

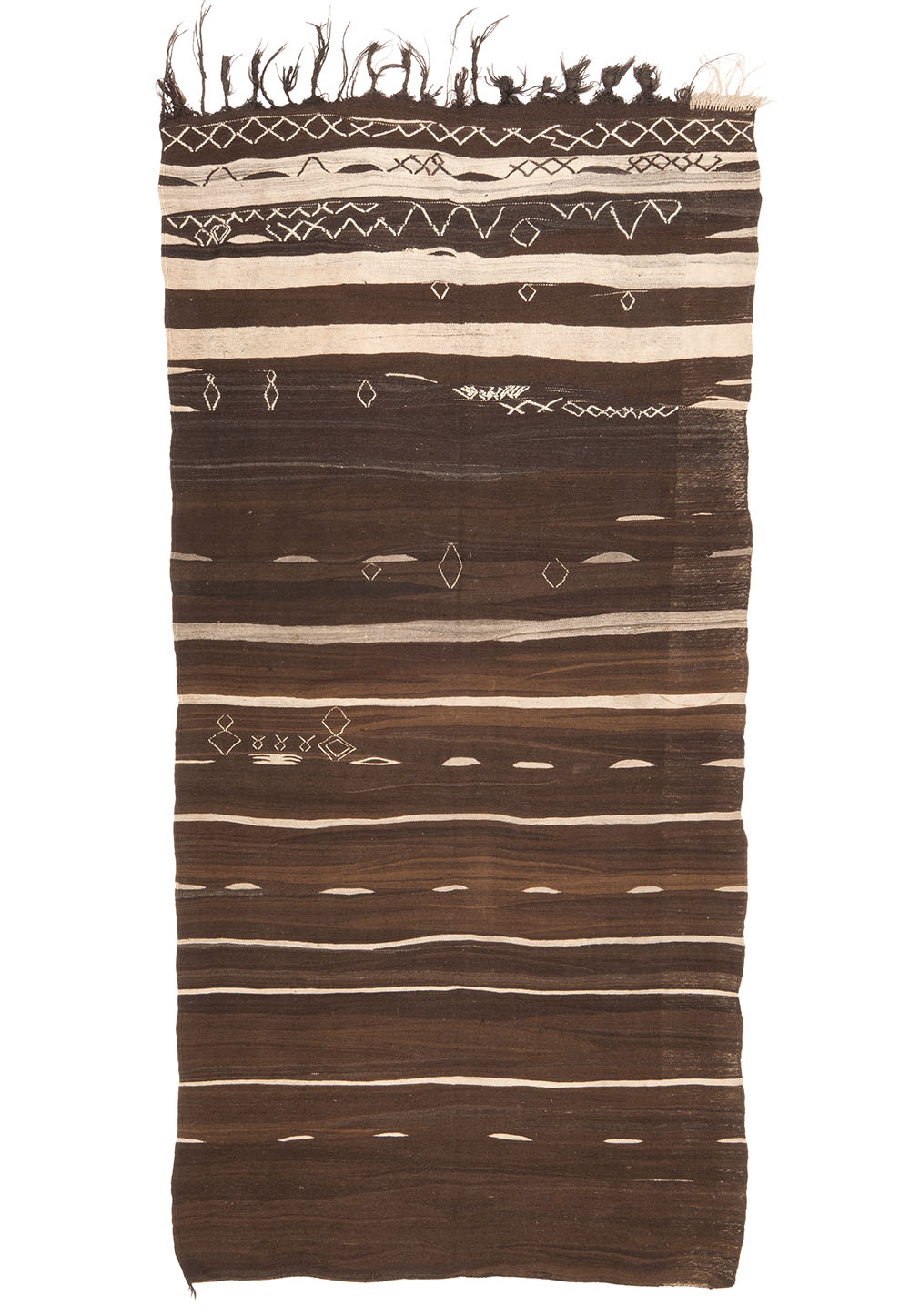

Berber haik, Mejjat tribe, Anti-Atlas, southern Morocco, second half 20th century. 1.15 x 1.95 m (3′ 9″ x 6′ 5″). Alexandra Sachs collection

Flatweaves in larger formats were traditionally produced in the rural regions of Morocco as tent decorations, floor coverings, blankets or transport bags. Particularly fine works were intended not for everyday use, but were usually made on the occasion of weddings, brought into the marriage by the women as dowry and subsequently seen only on special occasions.

The excellent work of the Zemmour tribe represents some of the best textile weaving found in the Middle Atlas region. Often of similar high quality are the kilims of the Ait Ouaouzguite Confederation in the Jebel Siroua area south of the High Atlas. Both became known and appreciated early on. While a complex mixture of weft substitution and weft wrapping techniques is used in the work of the Zemmour and most other groups of the Middle Atlas to create patterns, the Ait Ouaouzguite use weft twining and dovetailing tapestry weaving. These would seem to offer less scope for spontaneous, improvised design and potentially risk stereotypical repetition.

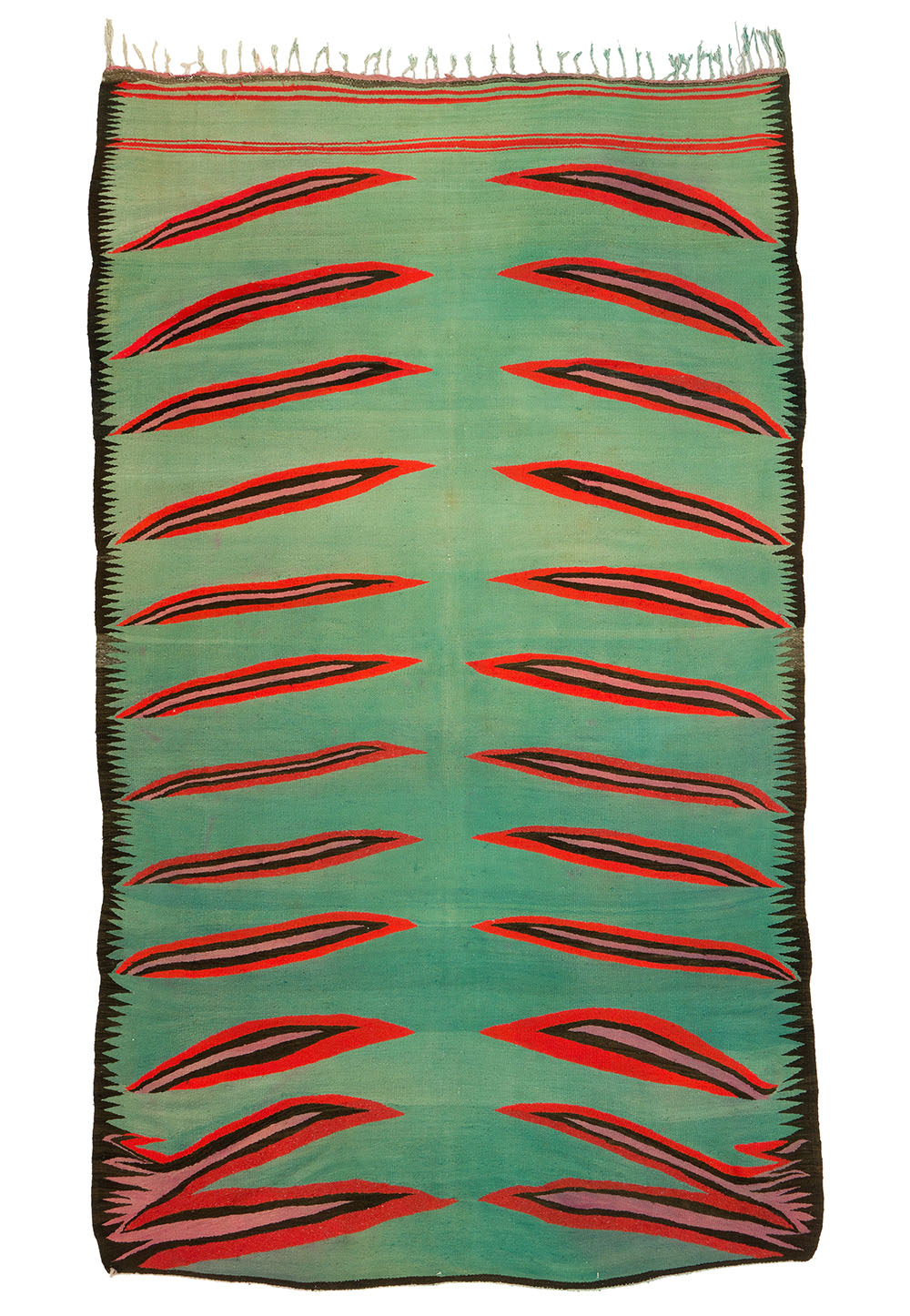

Berber flatwoven cover (taghalt) probably Beni Mguild, western Middle Atlas, Morocco, 3rd quarter 20th century. 1.70 x 3.25 m (5′ 7″ x 10′ 8″). Gebhart Blazek collection

Much less technically advanced flatweaves, whose designs are based on a clearly reduced formal language, are found in many regions of Morocco. Individual compositions are produced by individual weavers, who distinguish themselves by testing the boundaries of the cultural tradition within which they operate. Instead of intricate patterned bands we see areas in which refined colour compositions, delicate gradations and sometimes even brushlike stripes are used to create different effects. A weaver does not paint a textile in free gestures as one would on a canvas, but builds up the entire composition line by line as she weaves. An apparently impulsive and quickly achieved surface is thus in reality based on a process lasting weeks, the weaving proceeding with painstaking slowness. In other examples, hard contrasts and concise areas create a graphic quality presenting geometric shapes and iconographically placed motifs in the field. In very rare cases, such as some Ourika kilims, both painterly and geometrically defined properties are combined in the same textile.

In the Middle Atlas one can find kilims designed with carefully measured geometric proportions on the western side of the mountains in the border regions between the Ait Sgougou, the Beni Mguild, the Zayan and the Beni Zemmour, their southern neighbours (this latter group should not be confused with the Zemmour group who settled east of Rabat). Kilims with simple colour bands or surfaces are more common in the plains around Boujad and Beni Mellal (in the case of the Ait Roboa and Beni Moussa), and much further west (in the case of the Chiadma).

Cover from the Beni Mguild tribe Western Middle Atlas, 3rd quarter 20th century. 1.60 x 3.25 m (5′ 3″ x 10′ 8″). Gebhart Blazek collection. The first thing that stands out when looking at this flatweave is the intense blue background with a rich tonal gradation adding a sense of depth to the colour field. With a monochromatic background the weaver has created a striking vibrancy, reminiscent of the work of the German sculptor and artist Wolfgang Laib, whose ‘pollen fields’ break down representational form through the dominance of colour. The delicate motifs, which also appear in other flatweaves of the region, are the finishing touch comparable to a pinch of salt on an excellent dish. They are seemingly ephemeral yet very precisely placed, unobtrusive but perceptible owing to the strong contrast with the background, on which they sparkle like stars on the deep blue. One can detect a visual kinship to a bakhnough or a blue houli, a woman’s garment said to come from Tunisia or Libya (HALI 185, pp.86-93 ), but it is highly unlikely that the weaver intended to use such a textile as an inspiration for her creation. This rare and subtle piece shows a freer, more playful design than one usually finds in this type of textile

In the High Atlas, kilims without small continuous-patterned bands are known, especially from the Ourika Valley (see HALI 139, pp. 62–67). Further to the east, simple flatweaves, usually made of undyed white and grey, brown or black wool, are commonly used in everyday life as blankets and sacks. The kilims in the Ourika Valley are usually divided into light and dark stripes that reciprocally show light and dark lenticular motifs, often in vertical rows. In more recent pieces the contrast seems to be stronger; in older examples a subtlety due to gradients of undyed grey and brown wool in the stripes seems to occur more frequently.

Flatweaves in simple shades of grey and brown are also common among the more peripheral groups of the Ait Ouaouzguite Confederation and in many areas of the Anti-Atlas. In most cases these textiles show little variety of design but, as in the Middle Atlas, the individual creative achievements of a particular weaver can produce very attractive pieces.

Berber haik from the Mejjat tribe Anti Atlas, southern Morocco, second half 20th century. 1.10 x 2.20 m (3′ 7″ x 7′ 2″). Alexandra Sachs collection. In this textile the weaver has concentrated on a design that does not rely on colour to create a distinctive strong, graphic quality. The focus is on the undyed wool in various shades and on the simplified pattern repertoire used in everyday garments of the Mejjat region. These aesthetic principles allow for an unadorned design resulting in an almost modern contemporary appearance. The open field, with stripes and peaks running across it, has an effect not unlike the diffuse watercolors of J. M. W. Turner, defining vague outlines of a horizon. An endless range of shades adds depth and vividness to the light background. One can say that the entire composition is a virtuoso play with levels of density. However, the essence of this textile lies in the pure wool, the formal austerity and the rustic ‘worn over time’ patina. This haik resembles the headscarfs of the Ait Abdellah, with their unmistakable minimalist compositions, of which the best examples feature black peaks in the dark section (HALI 120, p. 79). There could clearly be a connection, since the Ait Abdellah are not situated far away from the Mejjat tribe. Ultimately this haik is one of very few examples representing the zenith of its genre

Such work is particularly conspicuous in the area of the Mejjat Group and further east in the Ait bou Nour in the extreme southwest of the Anti-Atlas; it is much less frequently encountered in other regions. Here at least one can speak of a typical regional weaving culture (see HALI 200, pp. 124–29). These textiles serve mainly as garments, though sometimes also as blankets, and are designed with a finely tuned play of grey and brown shades. In exceptional cases, the use of colour accents opens up an additional dimension of design.

Flatwoven kilim (hanbel), probably Beni Moussa or Ait Roboa, eastern central plains, Morocco, 1980s. 1.80 x 3.00 m (5′ 11″ x 9′ 10″). Gebhart Blazek collection

This kind of creative freedom is relatively rare in Moroccan kilims, though overall it is nevertheless typical of Moroccan textile culture, which not only permits such individual interpretations but seems actively to encourage them. In the best examples, the simplified design, the ‘less is more’ approach and the reduction of forms creates an enigmatic visual language which hints at a life beyond their use as unassuming textiles used as everyday objects—whatever the original intention of the weaver may have been.

In conjunction with the publication of his article ‘Striking simplicity’ in HALI 204, Gebhart Blazek celebrates the distinctive qualities of Moroccan flatweaves with an exhibition of Moroccan kilims at his gallery in Graz from 5 September to 3 October.

The exhibition will display the full variety of Moroccan rural flatweaves. Three of the pieces published will be exhibited together with other unusual examples of Moroccan kilims, among them a group of densely patterned examples from the Middle Atlas with bright colour combinations, juxtaposed with calm, earthy weaves from the Mejjat area in the most southern Anti-Atlas, a late 19th-century Zemmour kilim from an old US collection and a number of 19th-century examples from the Ait Ouaouzguite in the Taznakht region.

Comments [0] Sign in to comment