Academics in the Greek Archipelago

Francesca Leoni explains how a discovery in the Ashmolean Museum’s archives threw fresh light on an important area of British textile collecting—the acquisition of Greek island embroideries—and led to a new exhibition and catalogue.

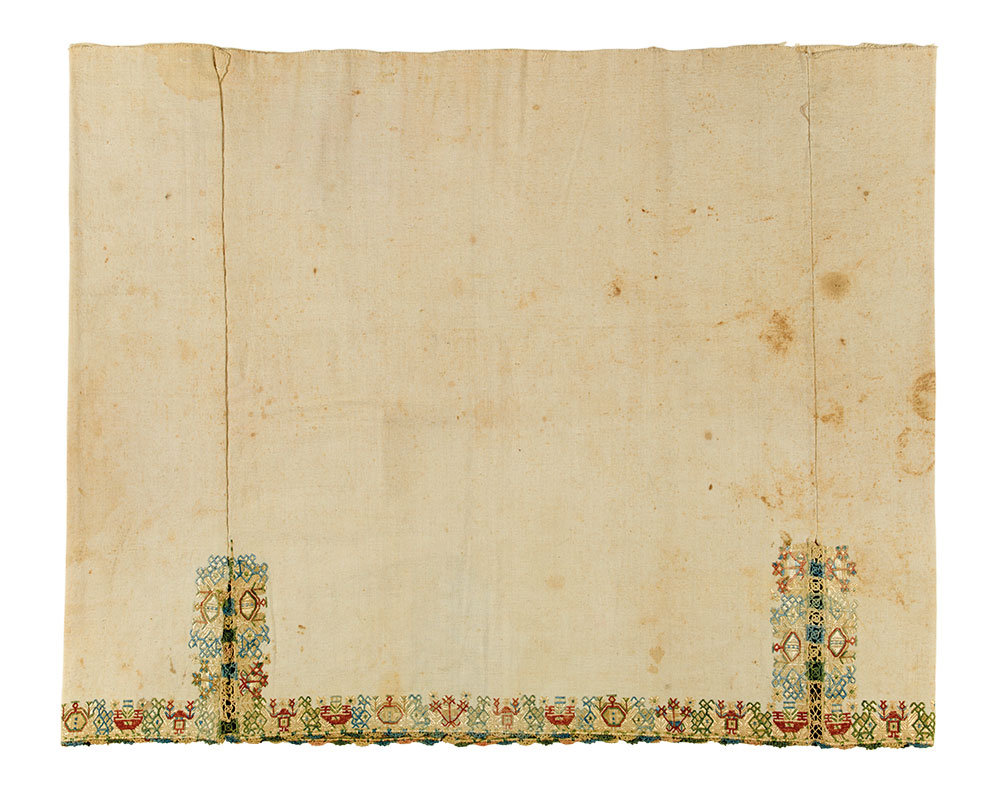

(1) Bed curtain (detail), Cyclades, 17th to 18th century. Silk on linen, 1.44 x 2.93 m (4′ 9″ x 9′ 7″). Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Oxford, EA1978.105a, Presented by John Buxton, 1978

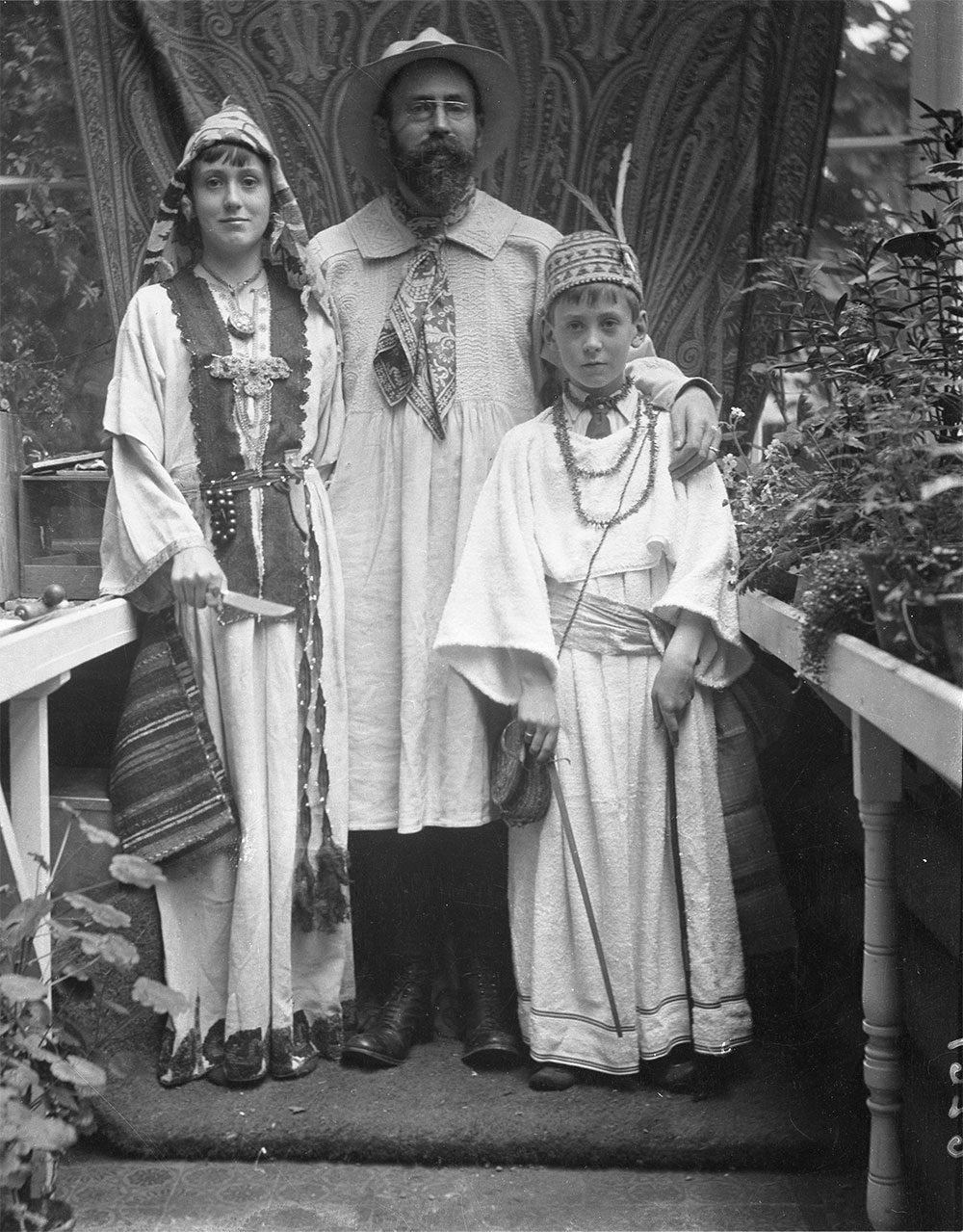

My first encounter with the Ashmolean Museum’s collection of Greek island embroideries was somewhat fortuitous. Pressed to create new curatorial folders for a group of old, typewritten catalogue cards, I came across a selection of black-and-white photos of textile fragments; they looked promising in spite of the images’ poor quality and the scanty accompanying information. Also attractive was the fact that these fragments appeared to be linked for the most part to two Oxford-based individuals: John L. Myres, Wykeham Professor of Ancient History between 1910 and 1939, and his student John Buxton. This added a ‘local’ dimension to a subject that has a distinctive place in the history of Britain’s textile collecting between the late 19th and early 20th century (1, 3). The contribution of British scholars to the acquisition and appreciation of Greek embroideries seemed ready to gain another chapter: the Oxford connection. This was a promising new avenue, especially given Myres’ relationship with the country’s most prolific collectors of these textiles, Alan J. B. Wace and Richard M. Dawkins (HALI 202, pp.98-107).

My subsequent exploration of this material and its origins has resulted in a small exhibition, ‘Mediterranean Threads: 18th- and 19th-Century Greek Embroideries’, centred on the rich cultural heritage of the archipelago. The catalogue, Aegean Legacies: Greek Island Embroideries from the Ashmolean Museum, offers fresh evidence about this tradition. It also illuminates the ways in which British historical research in Greece, the rise of anthropology, and the revival of embroidery inspired by the Arts and Crafts Movement, fostered appreciation in the UK. I am especially indebted to the generosity of several donors without whose support this publication would not have come to fruition.

(3) Chemise skirt border, Southern Cyclades, 18th to 19th century. Silk on cotton, 0.64 x 0.80 m (2′ 1″ x 2′ 7″). Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Oxford, EA1960.124, Bequeathed by Lady Myres, 1960

Like the installation, the book situates the objects in a Mediterranean context and against the economic and cultural networks established by the different powers that came to rule the Aegean. Twenty-five featured artefacts include curtains, valances, pillowcases, bedspread fragments and items of dress from across the principal islands (from the Ionians in the north to the southern Dodecanese and Rhodes in the south). They help introduce both the unique characteristics of these local creations and the shared material and cultural facets of Greece’s distinctive embroidery production.

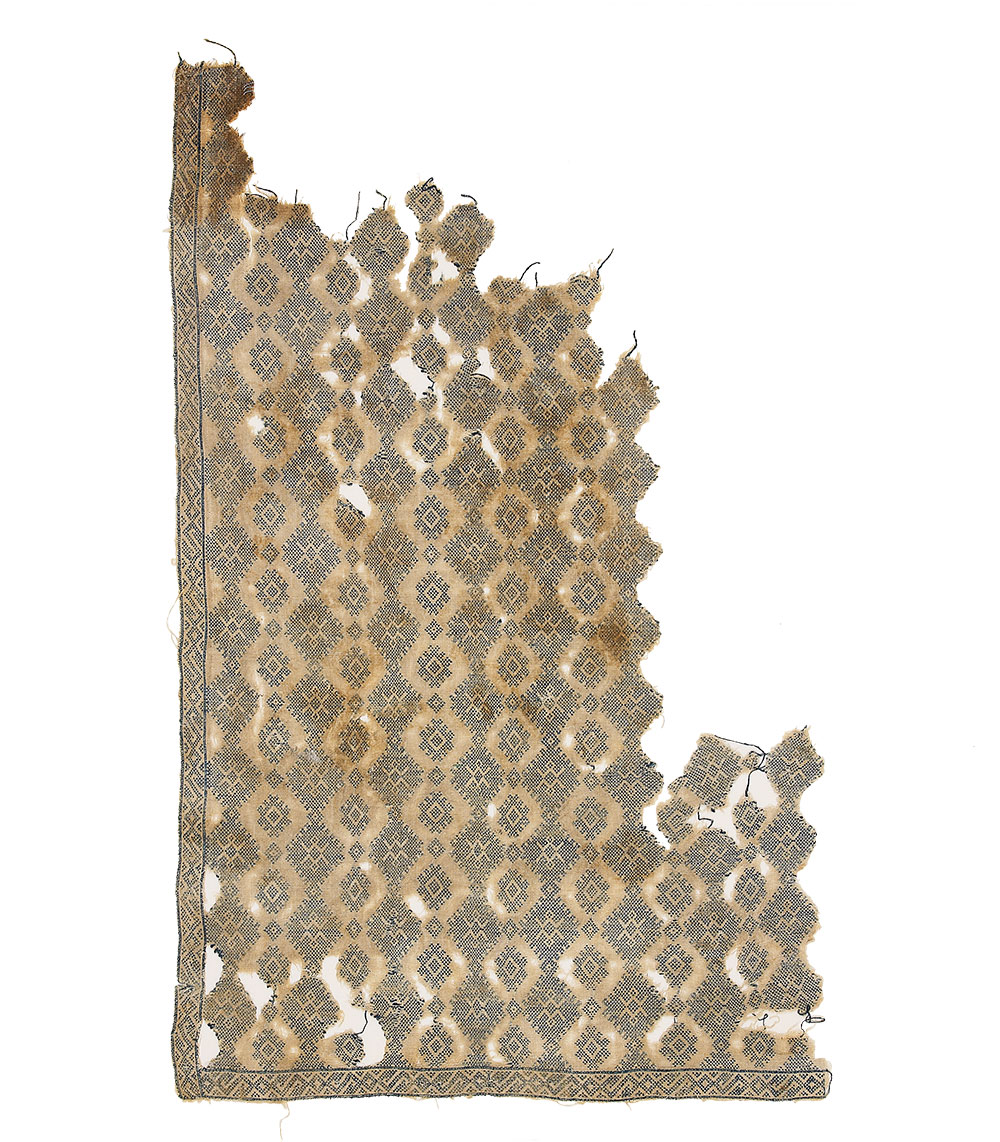

A few unique fragments add further evidence to familiar narratives, such as the impact of Italianate crafts and decorative motifs (5) as a result of Venice’s control of the Aegean, or the possible link with other important Mediterranean traditions, such as the Mamluk textile industry. The Ashmolean’s substantial medieval embroidery holdings from Egypt, acquired in the early 1940s through a significant bequest by Professor Percy Newberry (HALI 116, p.37), proved particularly valuable and revealing in the latter respect. They exposed further visual, technical and material parallels that strengthen the possibility of a direct relationship (7, 8).

(5) Fragment of a runner, probably Naxos, Cyclades, or Italy, possibly 18th century. Silk on linen, 25 x 34 cm (10″ x 1′ 1″). Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Oxford, EA1960.154, Bequeathed by Lady Myres, 1960

In light of the collection’s link with academia, the catalogue gives special attention to the influence of British research and of philhellenism on the acquisition and study of Greek ethnographic evidence. The intellectual interests of Prof. John Myres, in particular, reveal not only the probable motivations behind his acquisition of Greek island embroideries, but also the type of documentary evidence that these were believed to provide. Myres’s desire to get to the ‘essence’ of the Greek man—ancestor of western civilisation and a model for contemporary men—led him to explore Greek culture from multiple disciplinary angles (2). Thus philology, archaeology, geography, literature, anthropology and folklore converged in his quest for the origins and progress of Greece and the Greek people, enlisting material and visual evidence among the categories of cultural production that could document their spirit and genius.

(6) Bedspread, probably Ioannina, Epirus, 18th century. Silk on linen, 1.82 x 2.18 m (5′ 11″ x 7′ 2″). Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Oxford, EA1989.211, Presented by John Buxton, 1989

In this respect, Myres was the first to draw parallels between dialects, architectural styles and decorative arts including embroideries, envisaging them as repositories of ethnological characteristics. This is something his colleagues and fellow-collectors Wace and Dawkins would later seek to demonstrate more systematically. The fact that his collection, at least as presently known, privileges fragments and unusual examples over complete and visually attractive items would seem to support the idea that ethnographic and anthropological concerns were driving his collecting activities and selection.

(7) Textile fragment with diamonds and geometric patterns, Egypt, 13th to 15th century. Cotton embroidery on linen, 36 x 57 cm (1′ 12″ x 1′ 10″). Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Oxford, EA1993.75, Presented by Professor Percy Newberry, 1941

The rise of anthropology as an academic discipline at the turn of the 20th century, and its support of evolutionary theories, runs parallel to Myres’s study of Greek culture. Research in his archives, now held in the Bodleian Library, reveals his commitment to furthering the field and establishing a diploma in anthropology at Oxford, building on the success of a similar initiative in Cambridge in 1908. Interestingly, the extent to which the development of anthropological studies would then sustain race science and theories about civilisational superiority can also be followed in Myres’s archival documentation. This offers a snapshot on contemporary debates and on the political and ideological factors that sustained the rapid growth of this field. For the Oxford scholar, the past remained ‘a guide to the future’. The Mediterranean legacy, realised through the Greek example and felt as far as ‘the north’ (i.e. Britain), was sure to offer a key for the successful progress of the modern European world.

(8) Section of a bedspread, Naxos, Cyclades, 18th century. Silk on linen, 0.82 x 1.20 m (2′ 8″ x 3′ 11″). Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Oxford, EA1978.113, Presented by John Buxton, 1978

‘Mediterranean Threads: 18th- and 19th-Century Greek Embroideries’ is on view at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford until 19 September 2021. For a free pass from 17 May 2021, visit www.ashmolean.org. The catalogue, Aegean Legacies: Greek Island Embroideries from the Ashmolean Museum, is published by Hali Publications Ltd. and available from the HALI Bookshop.

Comments [0] Sign in to comment