Anatomy of an Object: Tushetian Kilim

A striking kilim recently offered by Istanbul dealer Şeref Özen is typical of 19th-century flatweaves from the mountainous region of Tusheti in northeast Georgia. Rachel Meek investigates.

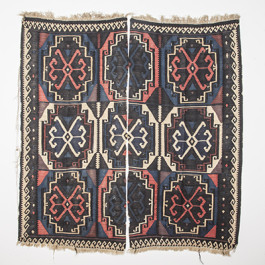

The ‘graphical and linear expressiveness’ of this flatweave is characteristic of pardaghi (kilims), traditionally produced in the Georgian region of Tusheti, as noted in the catalogue Georgian Rug, produced by the Georgian State Museum of Folk and Applied Arts for the first International Rug Festival, held in summer 2016 at the Rabati Fortress in Akhaltisikhe.

Very little else on this group is published in English at present, but there are good collections in the Georgian National Museum (GNM), as well as the local Tusheti Museum. The rugs were the subject of a PhD thesis written in the 1990s by Irina Koshoridze, director of the Museum of Folk and Applied Arts and chief curator at GNM. She suggests that the arresting designs on the earliest existing examples, dated to the 1850s, are indicative of archaic roots.

An almost authoritarian composition and a restrictive palette of mostly undyed black and white wool interspersed with decorative highlights of colour epitomises flatweaves made by Tushetians (or Tush). Along with the Khevsurs from the neighbouring northeast Georgian Khevsureti region—also situated on the modern border with Russia—they migrated from the highlands of their mountainous homelands and settled in valleys in the 1920s and 1930s. This led to a dramatic change in lifestyle, with the availability of modern goods and the decline and simplification of ‘folk art’ traditions. Tushetian kilims are one of the clearest ways to trace the altering visual language of the time.

Traditionally, natural dyes from barberries, Rhododendren Caucasicum (Georgian Snow Rose), madder and indigo were used. Synthetic aniline dyes were introduced in the 1870s and while only purple and orange shades were employed at first, by the 1930s the use of natural dyes had all but stopped completely.

Hooked black ‘Memling güls’ provide continuity across all nine main motifs on this rug, while the colour of their adjacent blocks and lines varies from section to section. White surrounds the main güls, as well as forming motifs within. In Georgian Rug, Koshoridze notes that ‘these white contour lines spread all over the main kilim space, and create one rhythmic composition which organically blends with the white border.’

Anatomy of an object

4 images

Learn more about the design elements of this Tushetian kilim.

- Stitching is visible down the length of the straight vertical lines of the black ‘Memling güls’, increasing the structural stability at a sizeable slit in the weave. Here, two colours meet without the interlocking teeth employed elsewhere. The use of two different shades of blue adds depth to the design.

- Tushetian kilim borders tend to be black and white with highlights of colour. While the ground of this piece employs a mostly naturally dyed coloured wool, the fluid Greek key border remains monotone.

- The squareish shape of this kilim is fairly standard for the group, but unusually, it has been woven in two parts—most likely due to loomwidth restrictions. The least used colour, yellow, is reserved for the centre of the middle row of güls and the outlines of the four corner güls.

- Slit-tapestry was most commonly used to weave kilims in Tusheti. The comb tooth effect on the vertical lines, stepped diagonal lines and hooked curls are decorative solutions to the limitations of this technique. The diamond motifs between the main güls provide a meeting point where there is a change between the positive and negative elements of the pattern being woven in white.

Comments [0] Sign in to comment