Around the World in Tie-dye

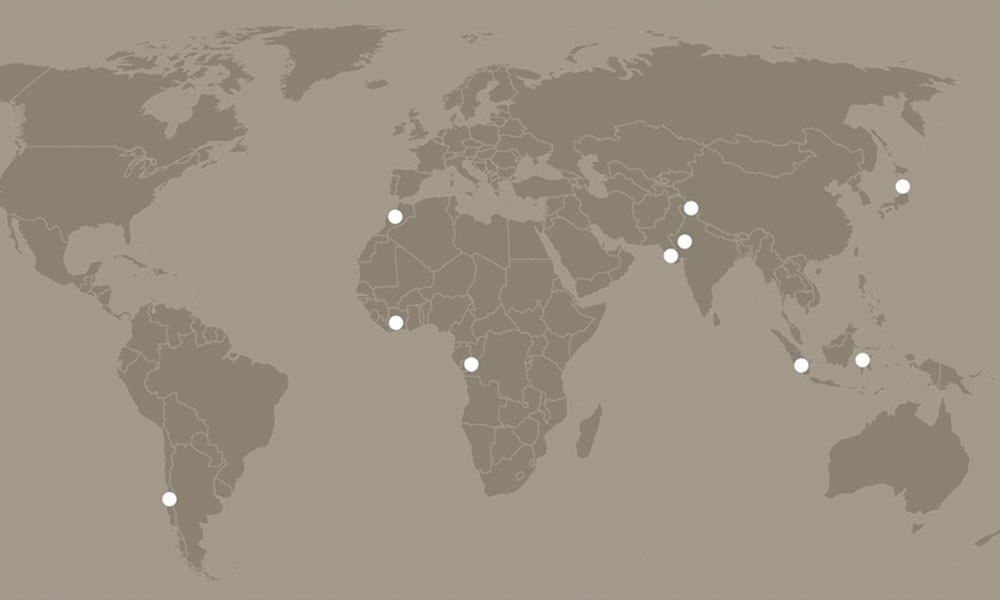

Resist-dyed textiles fall into three broad categories. The first, featured in HALI 200, is ikat, in which warp and/or weft yarns are pre-dyed before weaving. The second uses a resist medium such as wax, paste, mud or other compound, applied or painted onto the woven cloth surface, and will be considered in a later issue. The third, our subject here, comprises a variety of cloth binding and compression techniques that are popularly grouped together under the ‘tie-dye’ label, but are collectively best described as ‘shaped-resist dyeing’. Like ikat, shaped-resist textiles are culturally ubiquitous. Commonly known as shibori in Japan, bandhani and lahariya in India, plangi and tritik in Indonesia, and adire in Ghana, kindred techniques are also used extensively on textiles from southwest China, the Himalayas, North and sub-Saharan Africa as well as pre-and post-conquest South America. Sometimes these techniques of fabric decoration have arisen independently; sometimes they have been passed across cultures through trade and exchange, but it is thought that tie-dyeing often developed in conjunction with indigo cultivation. Specific local techniques, whether simple or more intricate, vary widely, but all rely on a few basic principles. Cloth may be drawn up and bound, stitched and gathered, pleated, folded, clamped, or tightly wrapped around a pole or other shaped object. It may be dyed repeatedly using different methods to ‘reserve’ areas from dye penetration during a vat-immersion or dip-dye process. The most basic patterns— circles, dots, lines, squares and diamond shapes—are typically repeated in varying sizes and scale. There is always an element of randomness and chance to the results.

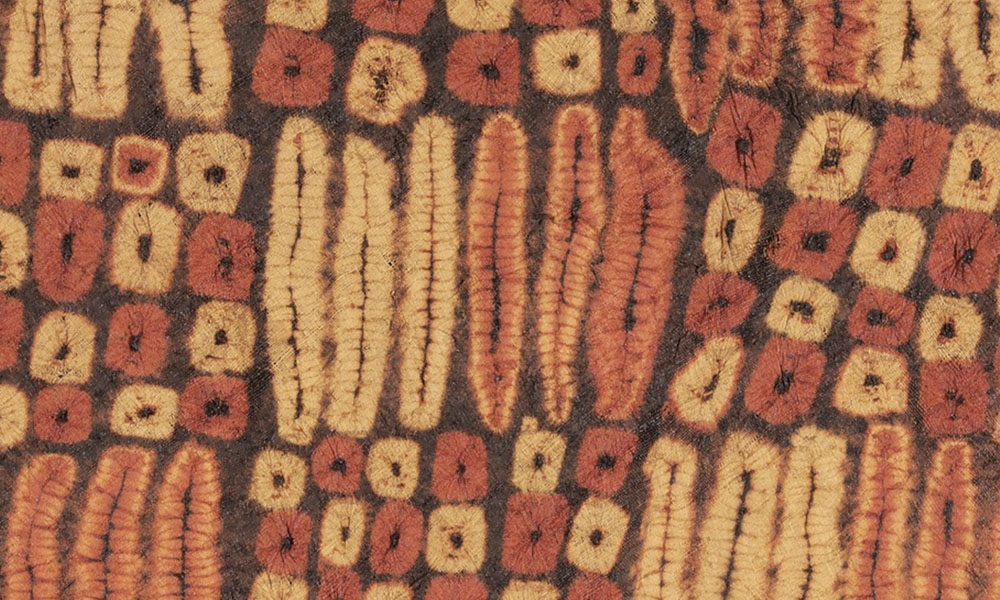

HIMALAYAS Sul-ma, woman’s woollen dress (detail), Ladakh, late 19th/early 20th century. Bill Liske Collection. Thigma tie-dye designs are found in Tibet and the Indian trans-Himalayan regions of Ladakh, Zanskar, Spiti and Himachal Pradesh. Known as a sul-ma, this style of garment, made from strips of snambu cloth patterned with thigma tie-dyed circles and cruciform motifs, was originally exclusive to the Ladakhi royal family, becoming more generally worn late in the 19th century.

INDONESIA Toraja pori roto ceremonial banner (detail), Sulawesi, 19th/early 20th century. Thomas Murray, Mill Valley. Plangi, the word used to describe tie-dye patterning throughout Indonesia, means ‘rainbow’. In the remote highlands of Sulawesi it was used on handspun locally woven cotton cloth or trade cloth by the Toraja people to create long ceremonial banners hung from bamboo poles or the tall roof peaks of traditional houses, Tongkonan.

WEST AFRICA Dida ceremonial skirt (detail), Côte d’Ivoire, 19th or 20th century. Andrés Moraga, Berkeley. In southwestern Côte d’Ivoire, Dida female weavers produced extremely fine linen-like cloths without the use of a loom from raffia-palm fibres which were plaited then dyed with natural pigments using hundreds of stitches to form a resist into dynamic compositions with low-relief sculptural qualities. They were worn as tubular garments and displayed during ceremonial dances by the tribal elite.

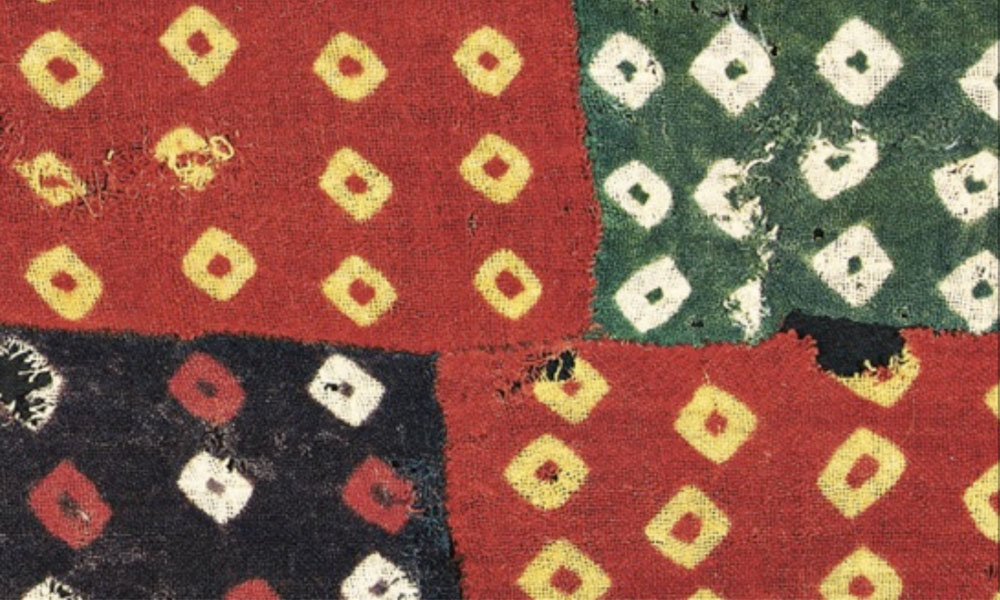

WESTERN INDIA Pagri, cotton turban cloth, late 19th century. Joss Graham, London. Lahariya (wave-pattern) was a tie-dyeing technique used to create the fine woven cotton prestige turban worn in the princely states of western India in the latter half of the 19th century. A narrow length of muslin was folded, tightly rolled on the diagonal, resist-bound with thread, and sequentially dip-dyed in a spectrum of colours. Untied, the resulting patterns were stripes and chevrons. By repeating this process in the opposite direction, the cloth could be cross-tied and dyed, resulting in checked or dotted patterns.

NORTH AFRICA Berber ceremonial veil (detail), Ait Atta tribe, central High Atlas, Morocco, first half 20th century. Gebhart Blazek, Graz. Known as ilbed n’tislatin, the visually compelling woollen veils of the Ait Atta Berber people in the central High Atlas region of Morocco are decorated using a simple tie-dye technique and were used for festive occasions and ceremonies. Like the neighbouring Ait Haddidou tribe, the Ait Atta women used worn woven wool fabric, normally taken from an old haik (large wrapping textile), to produce these veils.

JAPAN Festival kimono (detail), Akita Prefecture, Tohoku region, Honshu, late 19th/early 20th century. Thomas Murray Collection, Minneapolis Institute of Art, John R. Van Derlip Fund and Mary Griggs Burke Endowment Fund. The cotton fabric was decorated using several decorative tied and stitched resist methods known collectively as shibori. As there are many different types of shibori, Japanese textile artists specialised in one specific method of binding the fabric. This complex garment features folded and sewn (ori-nui) shibori for the outlines of the pictorial design and looped (miura) shibori to create the shading on the waterfall. The carp’s eye was created with capped (boshi) shibori, while the body features winding (makiage) shibori. The motif, koi no takinobori (carp ascending a waterfall), was a very popular design.

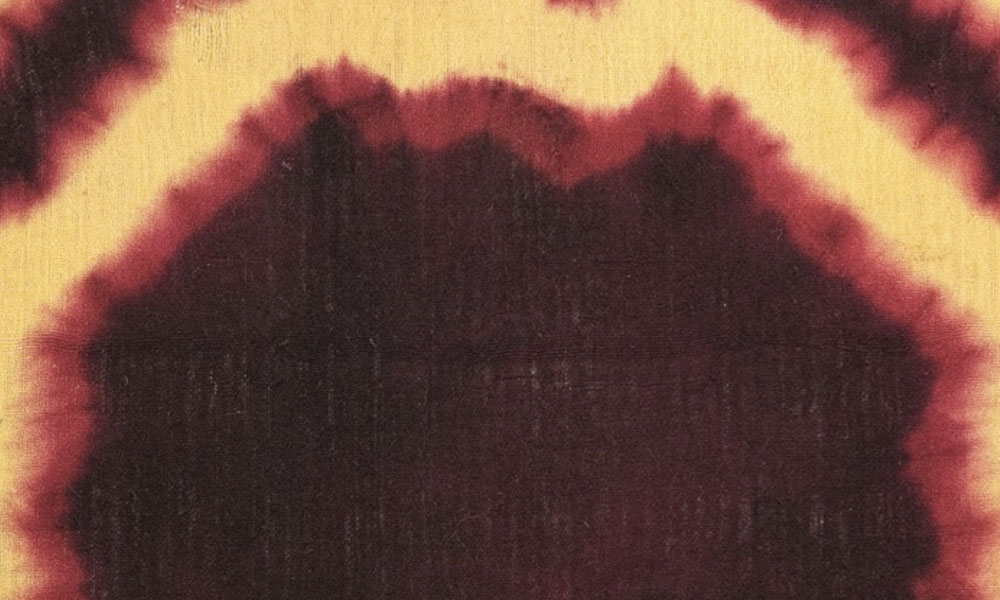

INDONESIA Woman’s silk ceremonial shoulder cloth, lawon (detail), Palembang region, south Sumatra, late 19th century. de Young Museum, gift of Thomas Murray. Lawon have been described by a local informant as shoulder cloths, slendang, and are worn by widowed women of high status. These highly graphic cloths are distinguished by large zone-dyed colour fields based on primary geometric shapes of diamonds and/or rectangles, the colours separated by stitched resist tritik borders, and are famed for their aesthetic resonance with the paintings of Mark Rothko.

CENTRAL AFRICA Kuba dance skirt (detail), Democratic Republic of the Congo, 19th/20th century. Andrés Moraga, Berkeley. Best known for their appliqué and embroidery, the Kuba (notably the Ngongo and Ngeende) were also expert dyers who exploited a variety of resist-dye methods to create large-scale ceremonial skirts for male and female titleholders. Here, the juxtaposition of a cane-stitch and folding technique generates linear patterns that are mirrored and reflected across diminishing saturations of colour in the central field. Irregular circular and lozenge tie-dye elements for border and inner panels yield a design of exceptional complexity.

WESTERN INDIA Woman’s silk dress, aba (detail), Kutch, Gujarat, first half 20th century. Heidi & Helmut Neumann Collection. Most Gujarati bandhani (tie-dye) textiles are women’s garments, mainly odhani, a veil cloth wrapping the body and covering the head. But bandhani is also used for saris and aba—the tunic-like dress worn by Muslim women with trousers and a veil—as well as kerchiefs in silk or fine cotton and long turban pieces in cotton. The intricate non-figurative pattern of botehs, squares and stylised flowers in this fine silk aba is typical for Muslim women from Bhuj. The tying was done not only for the small spots that make up the pattern, but also to reserve those parts of the dress that were required to remain yellow.

SOUTH AMERICA Cloth (detail), Nazca culture, Peru, ca. 300-600 CE. Alfred Ruppenstein Collection, Austria Auction Company, Vienna. Such Nazca/Huari cloths are among the oldest extant examples of tie-dyeing in the world, although rare examples from even earlier Andean cultures are known. Made in the discontinuous warp and weft technique from camelid wool, the fabric was woven in sections attached by temporary yarns passed through the warp loops. Areas intended to have diamond lozenge motifs were then bound with string, which would resist dye baths, and the tips were left exposed to form coloured centres.

Comments [0] Sign in to comment