Carpets and Textiles at the Florence Biennale

For the last few years, the largest number of firms exhibiting carpets and tapestries at a fair in Italy has been the annual exhibition held at Sartirana. Half a century ago, things were very different. The most important art and antiques fair in the world, bringing together many carpet galleries, was the Biennale Internazionale dell’Antiquariato in Florence. Michael Franses reports

Originally held at the Palazzo Strozzi, the fair reportedly drew some 170,000 visitors (HALI, Spring 1983, p. 76). Hali Publications Limited presented a most elegant stand in the foyer at the Florence Biennale in 1981 and 1983, designed by the architect Alberto Boralevi, then the representative of HALI in Italy. In those years, Alberto also produced an Italian language supplement of HALI. From when the Florence Biennale began in 1959 up until 1983, there were often as many as twenty major international exhibitors presenting tapestries and carpets. All the notable collectors attended from all over the world and a great deal of business was generally concluded. The Florence fair was ‘the place’ to bring your greatest carpets and ‘the place’ to sell them. The exhibitors included famous firms such as: Galerie Catan and Galerie Persane, from Paris; French & Co. and Vojtech Blau, from New York; Ulrich Schürmann, from Cologne; C. John, from London. Many of the top Italian galleries also attended, such as: Accorsi, Piero Barberi, Campana, Luciano Coen, Cerioli, Alberto Cittone, Elio Cittone, Giuseppe Cohen, Victor Eskenazi, M. Formanton, Dani Ghigo, Halevim, Dino Levi, Michail, Papazian & Eskenazi, Mirella Piselli & Luiz Santoro, and Daniele Sevi. From 1985 onwards, international art and antique fairs in other cities such as Paris, Munich, Maastricht, London and New York eclipsed the great Florence fair.

The Biennale Internazionale dell’Antiquariato has lasted some sixty years, and these days is held at the magnificent Palazzo Corsini on the banks of the Arno. As always, following a sumptuous black-tie dinner, Florence was treated to a spectacular firework display over the river. This year, just two Italian carpet and tapestry dealers exhibited: Mirco Cattai from Milan and Luciano Coen from Rome. Whether this reflects the state of the market or the rarity of great textiles is a question. The best carpet galleries have had to become more professional over the years and only the most serious firms remain at the top of the profession. Mirco Cattai presented an exhibition of Transylvanian rugs, together with some Chinese pottery figures from the Tang period. Cattai produced specifically for his presentation an excellent 46-page catalogue, Anatolian Rugs from the Ottoman Empire, written by the world authority Stefano Ionescu. Cattai is hoping to repeat this exhibition in his gallery in Milan in December.

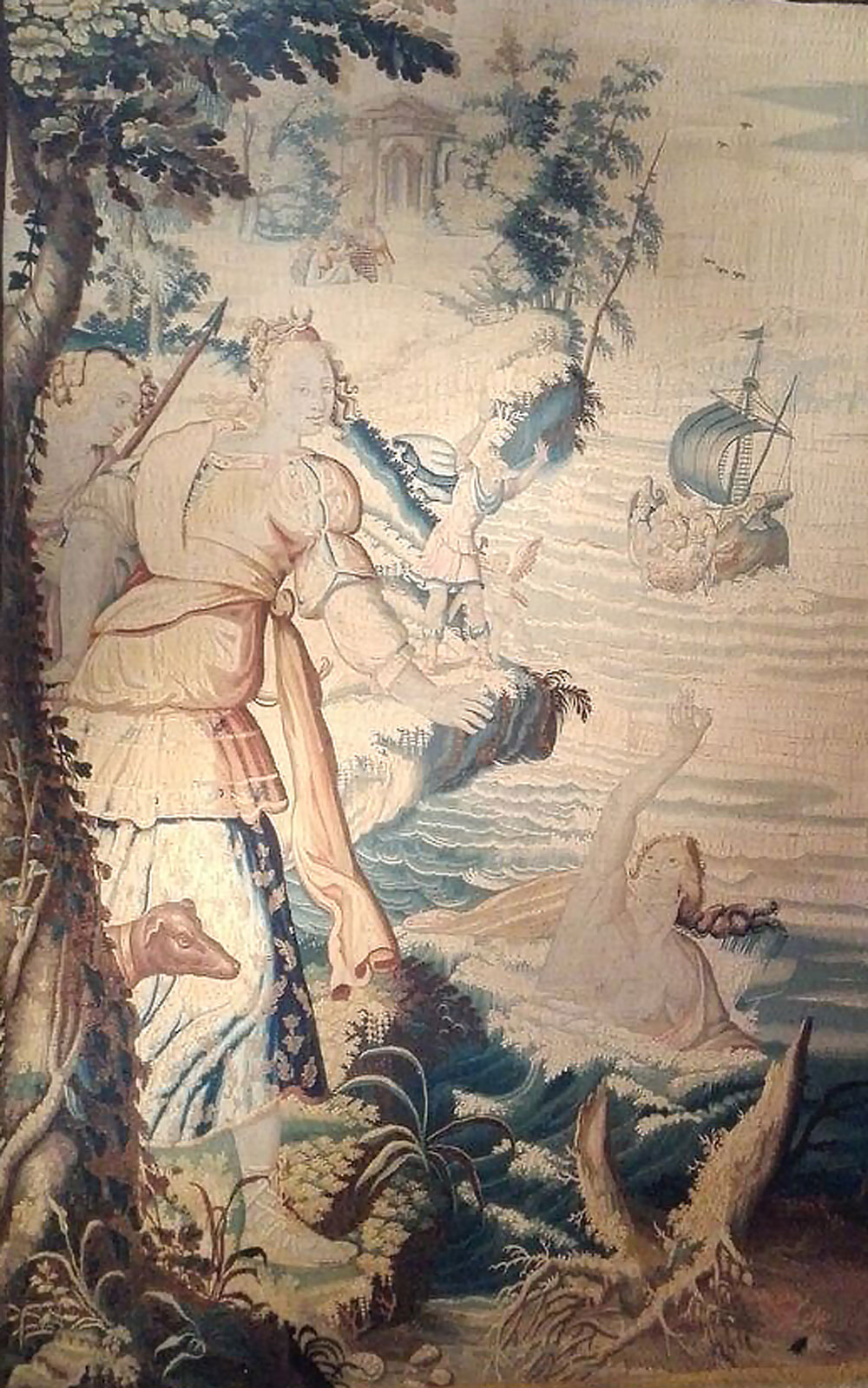

Andrea Coen, the director of Luciano Coen, the firm once known for having the most beautiful Peking carpets, showed an interesting and varied collection, including a fine Senneh rug and a beautiful Caucasian Seikhur that Luciano had purchased more than thirty years earlier at the Biennale from Dino Levi. Coen has done some remarkable research on a tapestry made in Paris in the atelier of Faubourg Saint-Marcel. It depicts Diana and Britomart, from the series of The Story of Diana, with the coat of arms of Dominique Séquier, Bishop from 1632 to 1637 and Commander of the Order of the Holy Spirit 1649. The tapestry was designed by Toussaint Dubreuil (1561-1602), painter to the court of Henry IV, and the provenance of the tapestry has been traced back through the centuries. Tapestries based upon the same cartoon are in the Cincinnati Art Museum and the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Probably my favourite exhibit on this stand was a classical English Elizabethan needlework valance with a design composed of five panels containing flowers and fruit.

Most surprising about the fair was that, although many 15th-17th century European paintings were presented, there was only one that depicted a carpet. One would have expected to have seen many more. The firm Michel Descours from Lyon presented a very fine Music Scene by François-Joseph Navez (Charleroi 1787-1869 Brussels), painted in Rome in 1819. The carpet depicted was made in Central Iran in the late 16th century, probably in Qazvin. The painting was purchased in 1819 by Claude Wolf, so-called ‘Bernard’ (Sri Lanka, 1785-1850), author, actor, singer, director of the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels, director of the Théâtre de l’Odéon from 1823 to 1826, and director of the Opéra de Marseille from 1828 to 1830. Whether this magnificent carpet belonged in 1819 to the artist Navez, to the buyer ‘Bernard’ or someone else is still to be discovered. Undoubtedly, the rendering of the carpet is so accurate that the artist must surely have had this carpet in front of him when he was working.

Florence is stuffed with breathtaking masterpieces of Renaissance art around every corner in palaces, churches and museums. The Palazzo Strozzi, once the home of the Biennale, always enthrals us with outstanding exhibitions. This year’s autumn exhibition there, ‘The Cinquecento in Florence’, which continues until 21 January 2018, is brilliant. The first two galleries alone (and there are plenty of great works later) are worth a special trip to Florence. Movies today start with a shocking scene that grabs the viewers’ attention. As one enters the exhibition, one is overwhelmed by the extraordinary beauty of Michelangelo Buonarroti’s monumental sculpture from 1526-7, River God, made in clay, earth, sand plant and animal fibres . Hanging behind this, is Andrea del Sarto’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ from the Uffizi. Painted between 1523-4 in oil on panel, this is possibly his finest work, the colours breathtaking and the composition perfect. The second room begins with Benvenuto Cellini’s unfinished marble sculpture of Apollo and Hyacinth from the Bargello made after 1546–certainly one of his greatest works. In the same room are three huge paintings of the Deposition from the Cross on wood: from 1521 in oil by Rosso Fiorentino, from the Pinacoteca and Museo Civico in Volterra; from 1525-8 in tempera by Pontormo, from Church of Santa Felicita; and from 1543-45 in oil by Bronzino, from Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’Archéologie, Besançon. Only such an exhibition can gather just the right masterpieces and present them next to each other. The exhibition has many other important works, in particular several bronze sculptures by Giambologna.

The Biennale was not the only attraction in Florence for carpet and textile collectors. The Boralevi brothers each presented rare and beautiful textiles in their galleries. Daniele, who specialises in contemporary carpets, presented in his gallery on Via Maggio for seven days only a special exhibition of Tappeti dell’Artigianato Abruzzese dal XVII al XX secolo from a private collection. Seven examples of these woollen flatwoven textiles were on display, the finest of them attributed to the town of Pescocostanzo and the early 17th century. Assembling such rare treasures is remarkably difficult, and the great sadness was that Daniele did not produce a catalogue recording his remarkable group. However, an excellent digital catalogue was produced in 2016, Tessere è Arte, by Erika d’Arcangelo, Gino di Paolo et al. for the Fondazione Genti d’Abruzzo, Pescara.

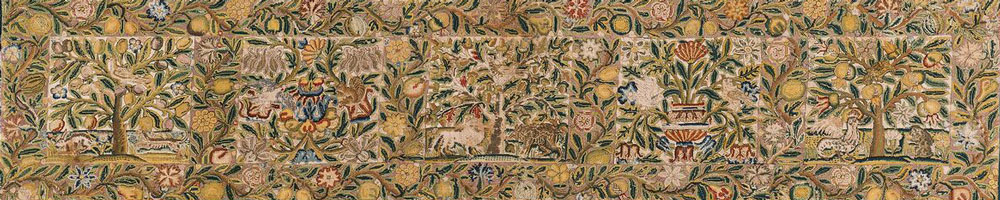

On display in Alberto Boralevi’s gallery on Via di Santo Spirito was an outstanding English needlework table carpet of the late 16th century. We are all aware of the great cost in England of ‘Turquey Carpettes” that were being purchased through Italy and France (Marco Spallanzani, Carpet Studies 1300-1600, Genova, 2016, pp. 49-70). This gave rise to copying Turkish carpet patterns in England, the Netherlands and elsewhere in Europe in the 16th century (HALI, 3, 3, 1981, p. 181). Boralevi’s carpet is almost a dead ringer for the so-called Charles I Table Carpet in the City of Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery (HALI 66, p. 96, no. 3). A quarter of a century ago, Ian Bennett and I attributed this carpet to the second quarter of the 17th century based on previous publications. Today, I might consider an earlier date, probably the second half of the 16th century. An example with similar flowers attributed to France or Alsace dated 1539 is in the Museum fur Kunsthandwerk, Leipzig, inv. no. 23.51.

The earliest dated needlework table carpet with ‘Holbein’ interlaced medallions is attributed to Switzerland, dated 1533, and has the arms of the Stokar and Tschlachan families from Schaffhausen; it is in the Landesmuseum, Zurich, inv. no. LM6097. The Boralevi needlework carpet has the added interest in that, apart from the large pattern Holbein eight-pointed star medallions and small-pattern Holbein interlaced guls repeating in the field, it has a secondary Holbein octagonal gul with interlace in the field. This can be directly related to the famous Salvadori Holbein variant carpet attributed to the last quarter of the 15th century, five sections of which are known: the largest is in the Keir Collection, Richmond, no. T20 (1988, pp. 55–6); another part was attached to the famous Bernheimer chair (HALI, 186, Winter 2015, p. 138); other sections are in the Victoria and Albert Museum , inv. no. 157-1908 and inv. no. 858-1902 (Hali, 1984, p. 362, figs. 1 and 2); and a part was once with Count Andrassy in Budapest. Equally fascinating is the border design on the Boralevi needlework, with a pattern taken directly from Damascus compartment carpets. According to John Mills (HALI, 4, 1, 1981, pp. 54-55), this border pattern can be seen as early as 1581 in a painting of the Circumcision by Marco Dall’Angolo in the Accademia in Venice. Numerous Damascus compartment rugs are depicted in English portrait paintings from the last quarter of the 16th and early 17th centuries that many must have been in England. Such glorious and fascinating needleworks offer so much art-historical information and are so rare they should be displayed by museums.

Comments [0] Sign in to comment