From Ningxia to Nichols

A selection from the collection of Chinese rugs of the New York-based Antique Rug Studio will be exhibited at the China (Qinghai) International Carpet Exhibition in Xining in June 2018. This article introduces the different types of carpets made for the domestic and export markets in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The following is based on the writing of Peter Saunders.

Pile-carpet weaving in China can be traced back to at least the early Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE). Excavations in western China have yielded relatively intact coarse pile rugs, now largely bereft of colour and pattern. The next surviving carpets are those commissioned by the Ming emperors for the Forbidden City palaces and woven in Beijing (Peking). Some of these carpets, often extremely large or of irregular shape, have remained in China while others have made their way westwards. With their white silk wraps, thick pile and dragon motifs, these imperial commissions have always been rare and never of a commercial nature. Outside of these two groups exists a wealth of Chinese carpets made for non-imperial and export markets, including pieces from Ningxia and Beijing, ‘Mongolian’ carpets and several types of Art Deco rugs.

Ningxia carpets

Ningxia is a ‘wool town’ in north-central China, bordering Gansu and Inner Mongolia. Carpets have been made there since at least the early 17th century for local sale and for use in mandarin and aristocratic houses in China proper. Almost all of the larger antique pieces exported in the late 19th-early 20th century were Ningxia in origin and there were literally thousands of them—Ningxia carpets are really the only antique Chinese type to be available to the collector in numbers.

Ningxia rugs are woven in virtually any format: large square audience (‘throne’) carpets; long and narrow kang carpets; pillar rugs; saddle rugs; chair seats and backs; and monastery meditation hall runners. The pattern range is similarly broad, but overall repeating textile patterns tend to be earlier (17th century) while medallions, often with lion dogs surrounded by cloud-wreaths, are somewhat later (18th and later centuries). Dragons often appear on chair covers, usually on yellow grounds. On large carpets, however, they are far less common. To place a chair on a dragon in an audience carpet would be in bad taste.

As with all true Chinese carpets, the knot is Persian open to the left (asymmetric). Antique carpets are quite coarse, 25-35 knots per square inch and double wefts often dominate the knots on the back. As a general rule, the older the rug, the more the wefts predominate. Thus, the knotting yarn on old pieces is relatively thin. Only with export demand in the west did thicker yarn come into use along with higher pile, to withstand shoe traffic.

Ningxia was the source for many of the pillar carpets for Tibetan and other Buddhist monasteries. Occasionally these rugs are inscribed in Tibetan character to give the patrons of the work and its intended location.

Beijing carpets

Commercial carpet weaving in Beijing is relatively recent – it was not until after 1850 that a real industry was formed. At that time there was a strong foreign demand for goods driven by a western mania for blue and white Chinese ceramics, and carpets were woven to match. Between 1860 and 1920 the Beijing carpet is remarkably consistent, displaying the following characteristics: western-room sized and uniformly Persian knotted on a white cotton foundation with double wefts, flat wraps, clean back and medium-high pile. The earliest pieces are quite thin and pliable, but the type gradually thickens.

In Beijing carpets, the blue and white colour scheme is almost universal: dark blue with a white border or vice versa. Designs of round smallish central medallions surrounded by floral sprays are most popular, but bold dragons and rare pictorials were also woven. There were many workshops, each employing about 20-100 weavers. Some carpets have relief cutting around the patterns of emphasis.

Since Peking rugs were strictly an export product, there are no chair seats, saddle rugs, monastery runners or other collectable types for specialised domestic markets. During the First World War, with the Persian export of carpets limited, Beijing workshops turned out pieces in Persian styles. These carpets are quite rare today and perplex many.

‘Mongolian’ carpets

Whether large carpets were woven in (Inner) Mongolia is an open question. If so, where were they made and what are they like? Presumed examples have pile wool that is coarse and relatively unsorted with kemp and hair fibres among the more desirable wool. The palette is often binary (blue or dark brown and natural ivory) and is always limited, never more than four colours. Patterns are simplified versions of Chinese compositions: bold medallions, often of the Shou type, and swastika fret borders. The overall look is strong and direct. A few pieces have dragons, large and centrally placed.

The carpets described above were made in an urban factory. Production was small and one diligent workshop could have made them all, but the question of where this workshop may have been located remains.

Nichols Art Deco carpets

What we understand as Chinese Art Deco period carpets are substantially the products of the Nichols Super Chinese rug Company of Tianjin (Tientsin) and Beijing from 1924 to the onset of the Second World War. The company was founded by the American W.A.B. Nichols and most of the carpets were made for export to the US. They were extremely popular and imitators sprang up to share in the success of the originals. The smaller factory in Beijing, housed in the former palace of a Manchu prince, featured a carpet showroom in the main audience hall, with the whole compound being popular as a tourist attraction.

The company produced its rugs almost wholly in-house, the only exception being foreign dyes. The normal size was 9′ x 12′, but custom orders were accepted and pieces up to 18′ 60′ were woven on demand. Very few runners or long and narrow carpets were woven. For a 9′ x 12′ carpet four weavers were employed on a vertical Tabriz-type loom with each carpet taking about 30 days to weave. Each weaver was responsible for a partial weft and these were overlapped where work joined. The knots are pounded down so well that there are no visible joins or diagonal lazy lines. Unlike most carpets, there are no complete wefts running across the carpet; the partial wafting made for faster production.

Designs fall into several broad categories, spanning more traditional Chinese and Chinese-inspired compositions along with more radical interpretations of Art Deco and motifs from the natural world and well as Buddhism and Daosim. Colours are saturated and appear in unusual combinations: red and gold, green and cranberry, black and white. Because of the extremely fast dyes, the colours still retain most of their vivacity and boldness.

Fette Art Deco carpets

A less well-documented but still sizeable and identifiable group of Chinese Art Deco carpets was the product of the Fette-Li Company, also in Tianjin. Mrs Fette, an American, partnered with Mr Li, a Chinese entrepreneur, in the 1920s to produce carpets in China for the (primarily) American export market, remaining active until the Second World War. Fette carpets are much more ‘feminine’ than Nichols rugs. If Nichols pieces are for the living room, Fette rugs are for the bedroom. The overall tonalities are softer, with more use of light colours and pastels—these are perfect Deco ladies’ boudoir carpets.

There are very few oval or round Nichols carpets, but Fettes are often found in these shapes. Tiny circular rugs with Chinese landscape or floral vignettes are a Fette speciality. Patterns are never starkly geometric and even though fields are unbalanced, there is not the Deco dynamism of the best Nichols production. The same general Chinese decorative vocabulary is used, however, staying just this side of obvious chinoiserie. Prunus branches, bamboo, precious objects from the scholar’s table, seasonal flowers and stylised rocks all appear. The tonality leans towards blue and white, and away from the novel chromatic juxtapositions of Nichols carpets. Many Fette pieces still bear identifying company labels on the back, often concealing coloured wool samples for the rug.

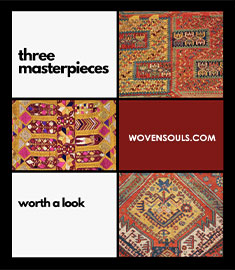

From Ningxia to Nichols gallery

3 images

- ‘Mongolian’ carpet, China, ca.1890

- Ninagxia pillar rug, China, ca.1850

- Art Deco carpet, China, ca.1920

Comments [0] Sign in to comment