A Selection from Auction Price Guide 2020

Auction Price Guide is one of the longest-running and most popular sections in HALI magazine, and a great place to learn more about specific carpets and textiles. Here we highlight six Auction Price Guide entries from HALI 205.

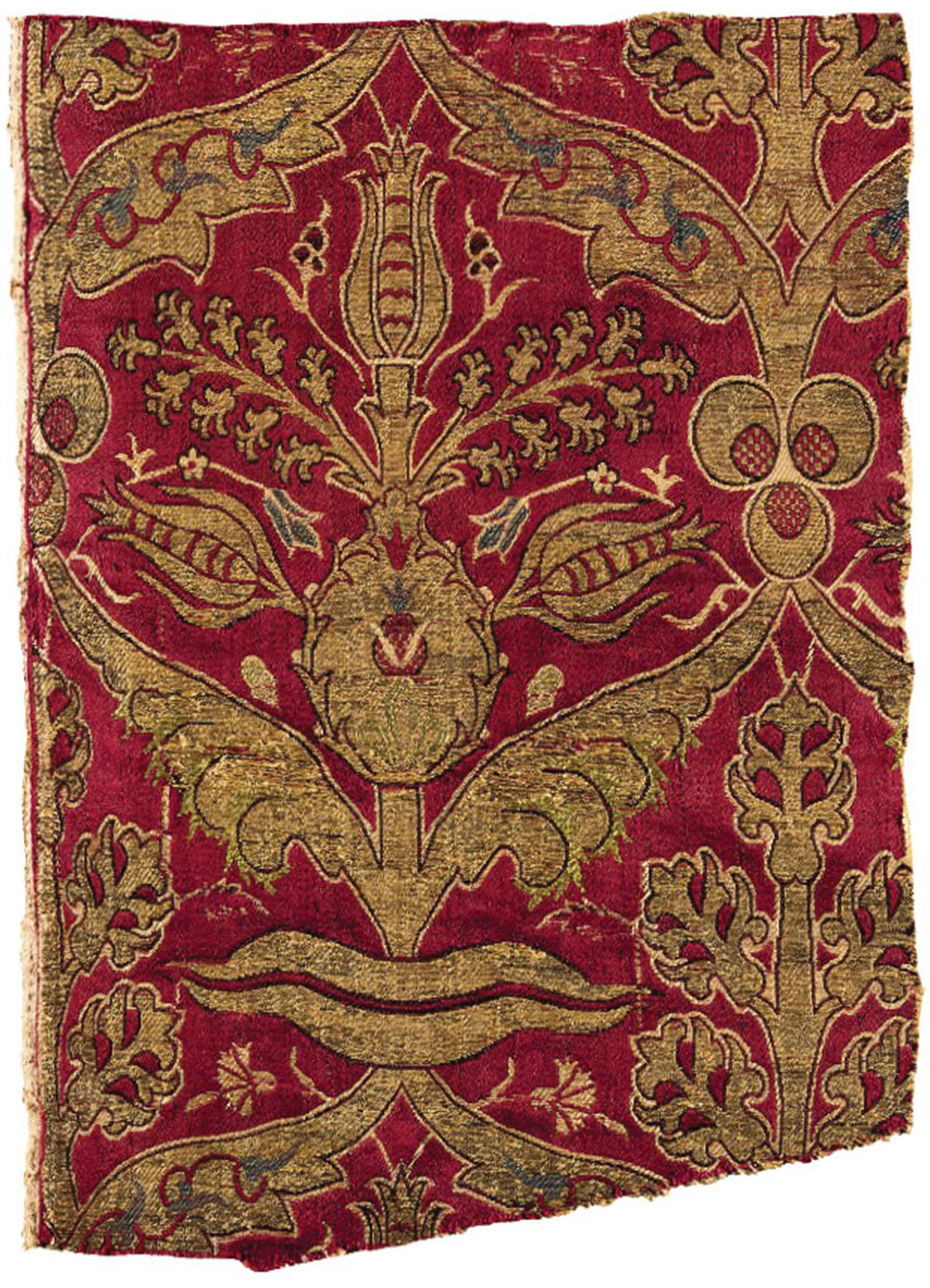

Ottoman kemha fragment, late 16th/early 17th century, 0.49 x 0.57 m (1′ 7” x 1′ 10”). Sotheby’s, London, 10 June 2020. Lot 123, est: £3,000-5,000, sold: £25,000 ($31,895)

This subtle design of golden strapwork is arranged in three layers. The uppermost has an ogival repeat of split-leaf arabesques. Each pair of leaves has a different design, one of diamonds and hexagons, the other a fine web of lobed flowers. These are linked either by palmettes enclosing tiny pomegranates or by trios of robustly drawn hyacinths. The next level is another golden ogival lattice connected by sets of three balls, or çintamani, with red chequered centres. Behind both of these, in total contrast, is a loose but delicately scrolling ogival trellis of slender white stems bearing a variety of small flowers, including rosebuds. They are depicted in a pale lavender-blue, black/dark brown and a clear pistachio green. The layering creates a surreal, three-dimensional effect, as if looking out into a garden filled with fragile blossom. This piece of silk and metal thread brocade is perfect for a museum: a rare design, good condition, a good size for a showcase, high-quality weaving with a full design repeat, and a selvedge. Museums do so love selvedges. It also has a handwritten note on an old collection card for ‘IMP. B. ARNAUD LYON_Paris: 96 Lampas oriental satin rouge á arabesques or & soie, 55/57’. The Kunstmuseum in Dusseldorf has a related example with the design on three levels (no.8786, Christian Erber, A Wealth of Silk and Velvet, pp.134-5, pl.G5/1), while the Keir Collection has another (Friedrich Spuhler, Islamic Carpets and Textiles in the Keir Collection, p.219, no.132).

Bahmanli rug, third quarter 19th century, 1.50 x 2.10 m (4′ 11” x 6′ 11”). Austria Auction Company, Vienna, 1 August 2020. Lot 24, est: €5,000-7,000, sold: €20,000 ($23,550)

Top lot in this sale, attracting numerous bids, this rug, while attributed by Austria Auction Company to Moghan (?), was probably woven in or near Bahmanli on the Iranian border in Karabagh. It is basically a descendent of large relatively early Transcaucasian workshop carpets containing recognisable cypress trees, here highly stylised. It is from the ‘rug boom’ period, which ramped up once the railroad from Batumi to Baku was completed in 1884. Early 19th-century versions of this type have a longer format, more design units, paler yellows and a more intense aubergine. Good aubergine dye fell out of use in Transcaucasian pile rug weaving by the mid-1860s. A somewhat comparable rug is dated the equivalent of 1872. Some of these early Bahmanli ‘cypress tree’ rugs were probably woven in workshops, because of the complexity of the pattern, the size and the evenness of colour.

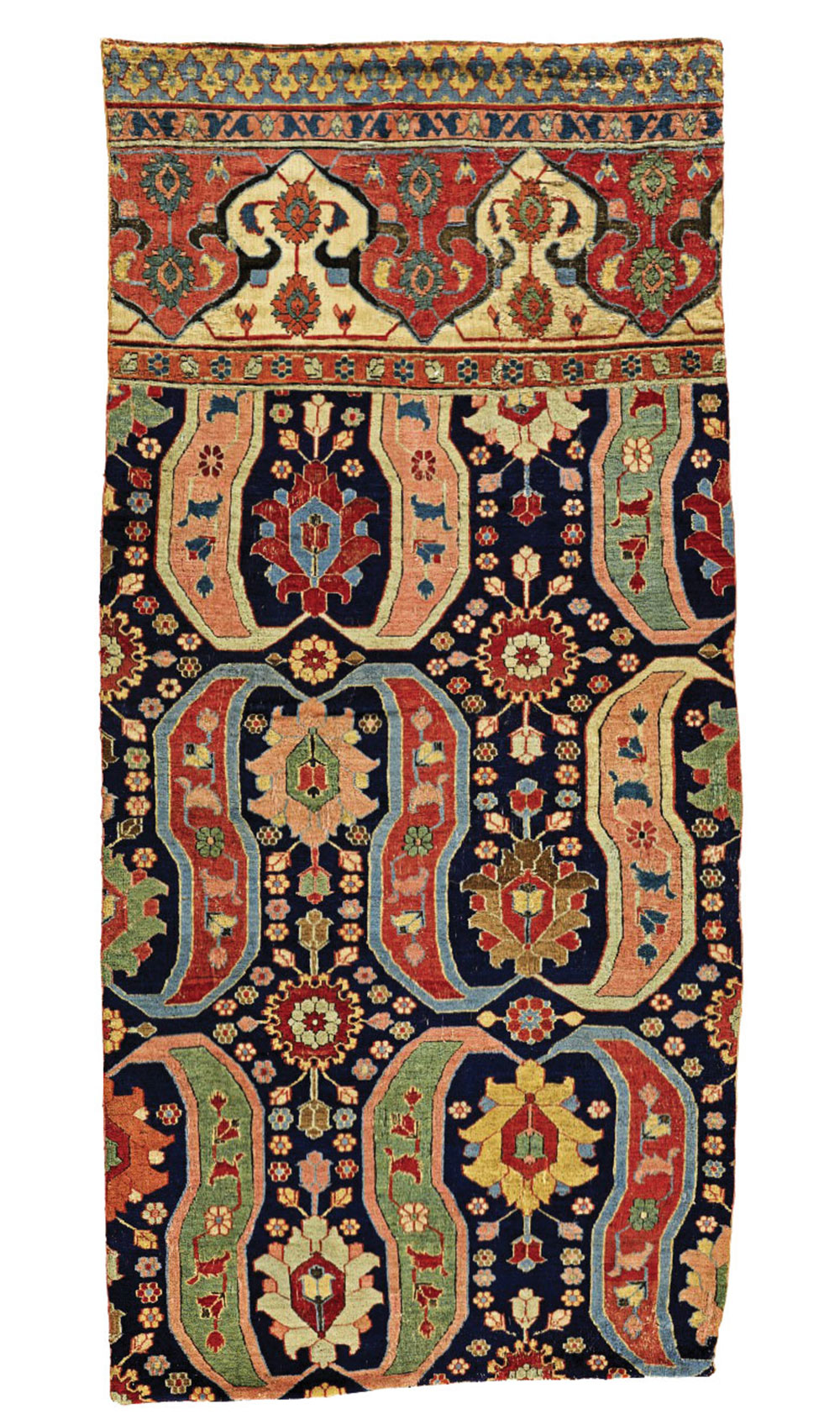

Khorasan carpet fragment, 17th century, 1.12 x 2.49 m (3′ 8″ x 8′ 2″). Sotheby’s, London, 10 June 2020. Lot 282, est: £30,000-50,000, sold: £35,000 ($44,650)

The first example of this design, with field and inner guard stripe, was sold at Sotheby’s, London, on 9 October 1991 for £30,800/$53,900 (estimate £6,0008,000, lot 2 = HALI 59, p.79 = HALI 60, p.150). Then Bernheimer had a fragment of just the main border (HALI 61, pp.62-3), and now this third piece shows the full picture, with the field and all its borders. All three have white cotton warps, brown cotton wefts, and jufti knotting, which fits with a Khorasan attribution, although the wefts are usually white cotton or occasionally silk. Structure apart, this field design is a bit of a mystery, and the only comparable main border with such similarly shaped large reciprocal trefoils is on a fragment in the Burrell Collection, Glasgow (HALI 172, cover and p.46, fig.1). But that is earlier, on a silk foundation, and with drawing in a different style. The field of our lot is dominated by large paired leaves, or waisted tulips, each with a kink in the middle. This seems to be an attempt at a 3D effect, to create an inward curving bulbous base with outward curling leaf tips above. Comparison of this piece with the 1991 SLO fragment suggests that they could be from more than one carpet, as the pink leaves on the 1991 piece have pale blue outlines but here they are in offwhite. The design of the 1991 example also seems to be slightly more elongated, and there are minor differences in the drawing of the details. We also wonder whether they may be 18th century, which could explain the lack of similarities to other 17th-century Khorasans.

Salor Turkmen jollar, 18th century, 1.21 x 0.41 m (4′ 0″ x 1′ 4″). Rippon Boswell, Wiesbaden, 27 June 2020. Lot 217, est: €7,500, sold: €40,920 ($45,905)

Exceeding the auction estimate more than four-fold, thereby reconfirming strong collector interest in Salor weavings as an elite class, this was a rather strong showing for a jollar (trapping) in less than perfect condition. The extensive use of ruby silk (subsequently corroded) might dissuade some from believing it to be an 18th-century example, but there is enough visual evidence to support the date. Apparently a ‘tribal’ example with little to no reference to more formal and classic design types, the field patterning was used by other Turkmen tribes, including the Arabachi and Ersari groups. The pile colours are brilliantly saturated with atypically luminescent medium and light blue hues as well as an apparently unfaded lemon yellow not seen in other examples. Based upon the borders, which conform to earlier models, it may be a little older than the trapping published by Louise Mackie and Jon Thompson (Turkmen: Tribal Carpets and Traditions, 1980, pl.13), though possibly not as early as the C-14 tested example featured by Jürg Rageth in his Turkmen Carpets. A New Perspective, 2016 (vol.1, no.10). Exact dating is uncertain as the Rageth result, though appropriately documented, is really too late for a C-14 analysis to be regarded as anything other than supplementary rather than definitive information. The condition issues were of no apparent importance to those who coveted this weaving, with the healthy price dictated by at least two determined collectors.

Turkmen embroidered asmalyk, first half 19th century, 1.27 x 0.55 m (4′ 3” x 1′ 10” ). Christie’s, London, 25 June 2020. Lot 178, est: £5,000-7,000, sold: £11,875 ($14,730)

The only early information on embroidered asmalyks is a comment by N. Burdakov, in his catalogue for an exhibition of his Turkmen carpets in St. Petersburg, in 1904 (see ‘The Carpets of Turkestan’, in Robert Pinner and Michael Franses, eds., Turkoman Studies I, London 1980, p.15). He noted that asmalyks were ‘rarely to be found among the Turkomans of the Merv oasis and those that are made are not woven but embroidered in silk’. Another clue comes from an example with a different design bought in Merv in 1902 by S.M. Dudin (Dennis R. Dodds and Murray L. Eiland Jr., eds., Oriental Rugs from Atlantic Collections, 1996, p.117, no.123). A piece with the same design as our lot was shown in the same exhibition, but the only provenance was ‘Collection of the former Museum of Peoples, Moscow’ (ibid, p.119, no.125). The attribution to the Salor was based on the finish at the top. A different piece, with the same design as ours, also called Salor, was the first embroidered asmalyk ever published, in 1941 (Alfred Leix, Turkestan and its Textile Crafts, Ciba Review, 40, Basel, republished in 1974 by Crosby Press, Ramsdell, p.50, pl.41). The evidence is a bit thin. All types are often attributed to the Tekke, based on similar stitches on the coats thought by some to have been made by them. This design falls into the group 13, defined by Daniel Shaffer and Penny Oakley in their review of embroidered asmalyks in HALI 180, 2014, pp.125-127). It is the largest group, with some on a wool foundation and some on cotton, but this is the only example of this type with human figures, two couples at the top left. And is there also a tiny dog in the top left corner? This piece, sold for £6,875/$11,045 at Sotheby’s, London, on 8 October 2014, lot 189, estimate £4,000-7,000 (HALI 183, p.133), is embroidered in silks, with wool details, on a wool ground, with the design sketched on the front before embroidery. A good profit, and bravo to Christie’s for their superb online images—and one of the back.

Ningxia pillar rug, mid 19th century, 0.94 x 1.57 m (3’0″x 5’2). Rippon Boswell, Wiesbaden, 27 June 2020. Lot 207, est: €8,000, sold: €12,500 ($14,025)

Many people would not be able to stand upright in a room with pillars of such a small size. One might therefore speculate that this dragon rug was made in western China specifically for the pillars flanking a large Buddha statue on a raised plinth, as one sometimes finds in Tibetan monasteries. The dragon is dynamically drawn with a large flowing tail, and as as usual is depicted flying over the cosmic ocean and Mount Meru chasing the flaming pearl. Above there is a typical Tibetan pearl curtain providing context to the monastery. The dragon’s snout has a ‘pepper and salt’ colouration in blue and white, a technique we find more ften in Tibetan than in Chinese rugs. Unfortunately, the colours of the rug seem to have lost a bit of intensity since it was first published by Eberhart Herrmann in 1985, Seltene Orientteppiche VII, no, 92 (or were they perhaps enhanced then?). A blue ground seems to be rarer for pillar rugs than a beige one. Another blue-ground example, but of more usual dimensions, was sold in the same rooms on 25 May 2019 for €15,990/$17,915 (HALI 201, p.139).

Comments [0] Sign in to comment