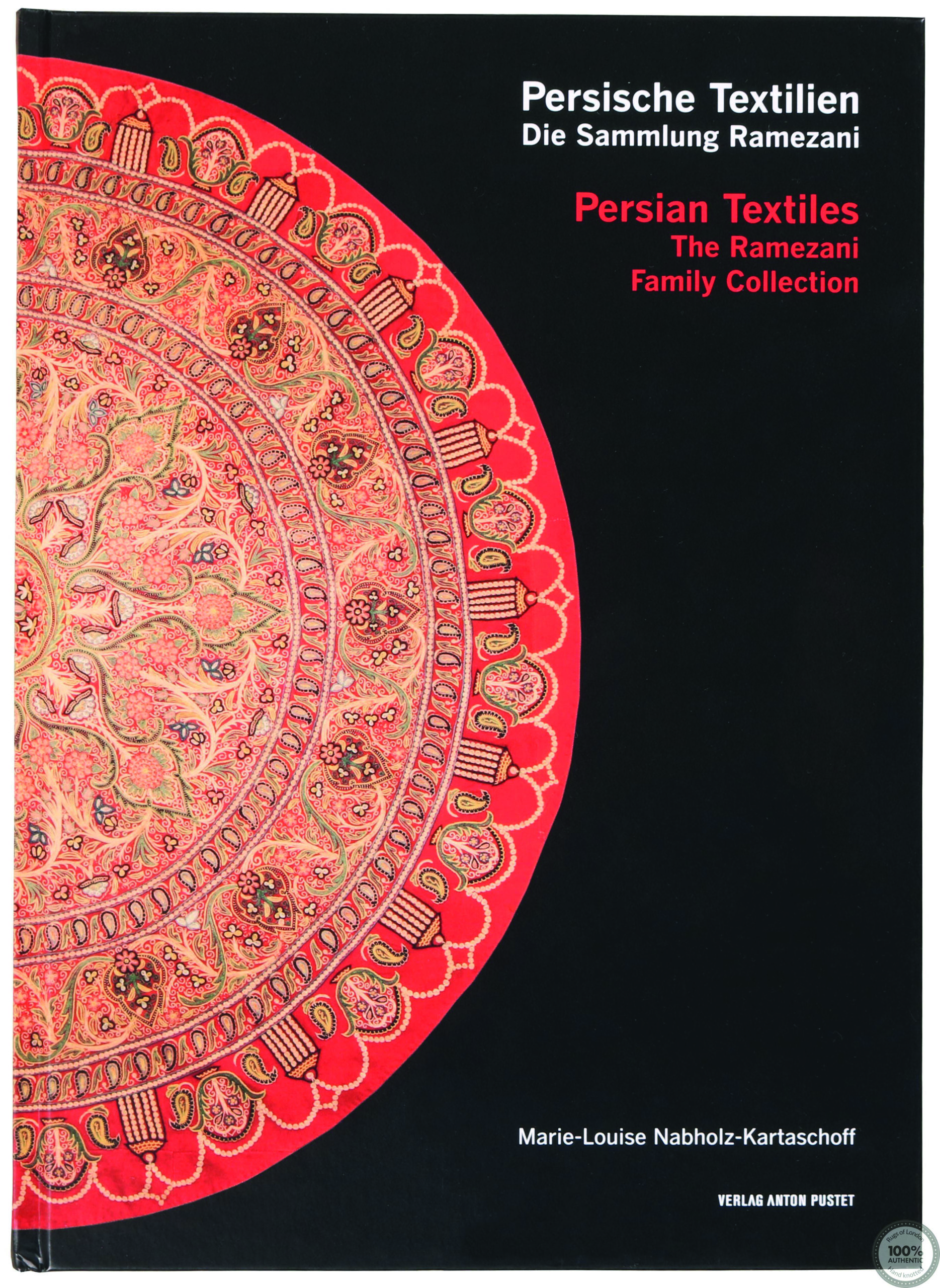

Book Review: Persische Textilien: Die Sammlung Ramezani/ Persian Textiles: The Ramezani Family Collection

Persische Textilen: Die Sammlung Ramezani/ Persian Textiles: The Ramezani Family Collection. By Marie-Louise Nabholz-Kartaschoff. Reviewed by Jennifer Scarce

Persische Textilen: Die Sammlung Ramezani/ Persian Textiles: The Ramezani Family Collection. By Marie-Louise Nabholz-Kartaschoff.

Persia is remarkable for its architecture, the arts of manuscript illustration and calligraphy, the crafts of ceramics, metalwork and much more. But arguably its most versatile and wide-ranging achievements are in the textiles essential to all levels of society. These artefacts fulfil many needs, from the structure of the nomad’s tent, saddlecloths, household furnishings and prayer carpets to clothing.

From the precious surviving patterned silk fragments of the Sasanian period (3rd to 7th centuries ) onwards, a wide range of resources were available. Natural fibres included cotton, flax, silk and wool, supplemented by animal skins for leather. Weaving was the dominant form of production. Professional court and city craftsmen, with their complex draw looms, mastered a repertoire of plain, twill, tapestry and knotted techniques. These could be further embellished with supplementary metallic threads, embroidery appliqué, block printing and painting. Village and nomad weavers, meanwhile, used simple looms to make knotted wool carpets, covers and storage bags.

A flourishing dyeing industry created multicoloured surfaces for design, and rich hues were favoured. Dyes were made from plants, insects and mineral substances. The design repertoire was vast, having developed over centuries of production. There were many variations on floral and foliate themes, and also figural scenes such as hunting parties, picnics in meadows and narratives inspired by Persia’s epic and romantic poetry and folklore.

As textiles evolved, specific regions of Persia became famous for particular products. These were praised in contemporary accounts, written in Arabic and Persian and later in European languages as diplomatic and trade missions arrived. During the 12th century, for example, the city of Kazerun in Fars province was a major centre for fine linens, which were widely traded and exported. Khorasan produced a brightly coloured silk worn by royalty and court offi cials.

Much later, in the 17th century, the sumptuous Safavid capital of Esfahan was especially renowned for the range and quality of its brocaded silks (used for both furnishing and clothing), and for knotted carpets, which were also woven in Kashan and Kerman. Equally fine work was produced during the long reigns of Fath-Ali Shah (r. 1797–1834) and Naser al-Din Shah (r. 1848–1896) of the Qajar period (1786–1925), who ruled from their capital of Tehran.

Among the abundance of publications on Persian textiles there is either nothing or little about the range, fine workmanship and design of Qajar textiles (the exceptions being the books and articles of Dr Patricia Baker and Jennifer Wearden on the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum). The publication under review here is a welcome introduction to the Ramezani Family Collection. A selection of sixty-six representative pieces are clearly photographed in colour and accompanied by a well-researched text.

2 Qalamkar hanging, Esfahan, late 19th century. Cotton block-printed and painted with a scene of Shah Tahmasp I receiving the Mughal Emperor Humayun in 1540

Hossein Ramezani provides an introduction drawing on his wide knowledge of textiles and his experience in assessing and forming a balanced collection. Dr Marie-Louise Nabholz-Kartaschoff, former Curator of the Department of Asian Textiles in the Museum of Cultures, Basel, has used her knowledge and professional skills to classify, catalogue and interpret the pieces in their historical and social context. Her text is supplemented with contemporary images of weaving, sewing and details of motifs and stitches.

Within the limits of a review it is possible to select only a few examples to illustrate the variation and sophistication of technique and design. One of the most versatile fabrics was the zarbaft of Esfahan and Kashan. A fine silk brocade woven with repeated floral cone (boteh) and palmette motifs, it could be adapted for furnishings or clothes. It was a popular choice for court women’s jackets (1), which were short, tightfitting and had long, pointed sleeves. They were worn over long skirts or voluminous trousers.

But during the late 19th century fashions changed to favour layers of short, flounced skirts reputedly influenced by European fashion. Kerman continued to be a renowned centre of textile production catering for furnishing and clothing needs with a wide range of woven and embroidered fabrics. Fine red wool woven in twill weave was suited to the pateh-duzi technique (3) where designs were meticulously embroidered with multicoloured silks in flat stiches. Wall hangings and curtains were particularly suited to displaying elaborate design schemes of cypress trees and birds within a framework of quarter medallions and borders comparable to those also found in knotted-pile carpets.

3 Curtain, Kerman, late 19th century. Red wool in twill weave embroidered with coloured silks in pateh-duzi technique with a design of a cypress tree among birds

In the late 19th century the Caspian town of Rasht specialised in rasht-duzi, a distinctive and spectacular embroidered textile used primarily for furnishings, including wall hangings. Covers and upholstery were shaped to fit the European-style chairs fashionable in the decoration of court and upper-class houses during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Here (4) a mosaic patchwork in strong reds, greens, yellows and black was stitched together and ornamented with appliqué and embroidered detail in contrasting colours.

Popular designs consisted of formal schemes of floral and foliate medallions within deep borders, but there were also compositions with figural subjects—portraits of Qajar princes and their European contemporaries. Narrative scenes also abounded, treated in a manner possibly copied from widely circulated contemporary lithographs of familiar and loved scenes from Persian poetry. Against the background of a red wool hanging—liberally scattered with embroidered flowers, birds and animals—are three famous scenes from the Shahnama, Ferdowsi’s national epic, and the romantic verses of Nizami. Princess Shirin watches the sculptor Farhad digging through Mount Bisitun; Prince Bahram Gur hunts with his favourite Azadeh; and Layla visits Majnun in the desert.

The decoration of Qajar textiles was not limited to embroidery. Yazd, while continuing as one of the towns respected for the quality of its silk textiles, also experimented with dara-i, the trade name for a complex and time-consuming ikat technique. Warp threads were tie-dyed in varying colours and lengths, producing blurred, fringed edges to medallions, cartouches and striped patterns. Squares of dara-i fabric were used as wrappers (boqceh) for taking soaps, bowls, etc to the bathhouse; for gifts; and also for storing bundles of household textiles and clothing.

The use of pictorial themes already seen in rasht-duzi work was further developed in Esfahan’s famous qalamkar cotton textiles: carved wooden blocks were used to stamp motifs outlined in black which were then filled with red, blue and yellow. Clusters and groups of boteh, floral and foliate motifs and scrolls were assembled into a repertoire of designs suitable for both furnishings and garments.

Within the frame of a printed border it was possible to introduce pictorial scenes (2) painted directly on to the cotton fabric. There was plenty of choice: depictions of Shah Tahmasp I (r. 1524–1576) receiving the Mughal Emperor Humayun in 1540, copied from the painting in the Chehel Sotun Palace of 17th-century Esfahan; portraits of Qajar and later dignitaries; or scenes of everyday life. Qalamkar paintings were practical items of interior decoration as they could be rolled up and moved, stored and transported between residences.

Collectively, through a fusion of tradition and innovation, all these textiles offer a view into the vitality of Qajar culture.

Comments [0] Sign in to comment