HALI Book Review: Tudor Textiles

Working with the primary source material of one’s book should be a decided advantage. It certainly means Lynn is well placed to argue her opening premise: that textiles were at the heart of the Tudor court and were primary signifiers of wealth, prestige and power. Tudor textiles cost more, and were valued and collected more, than any other art form.

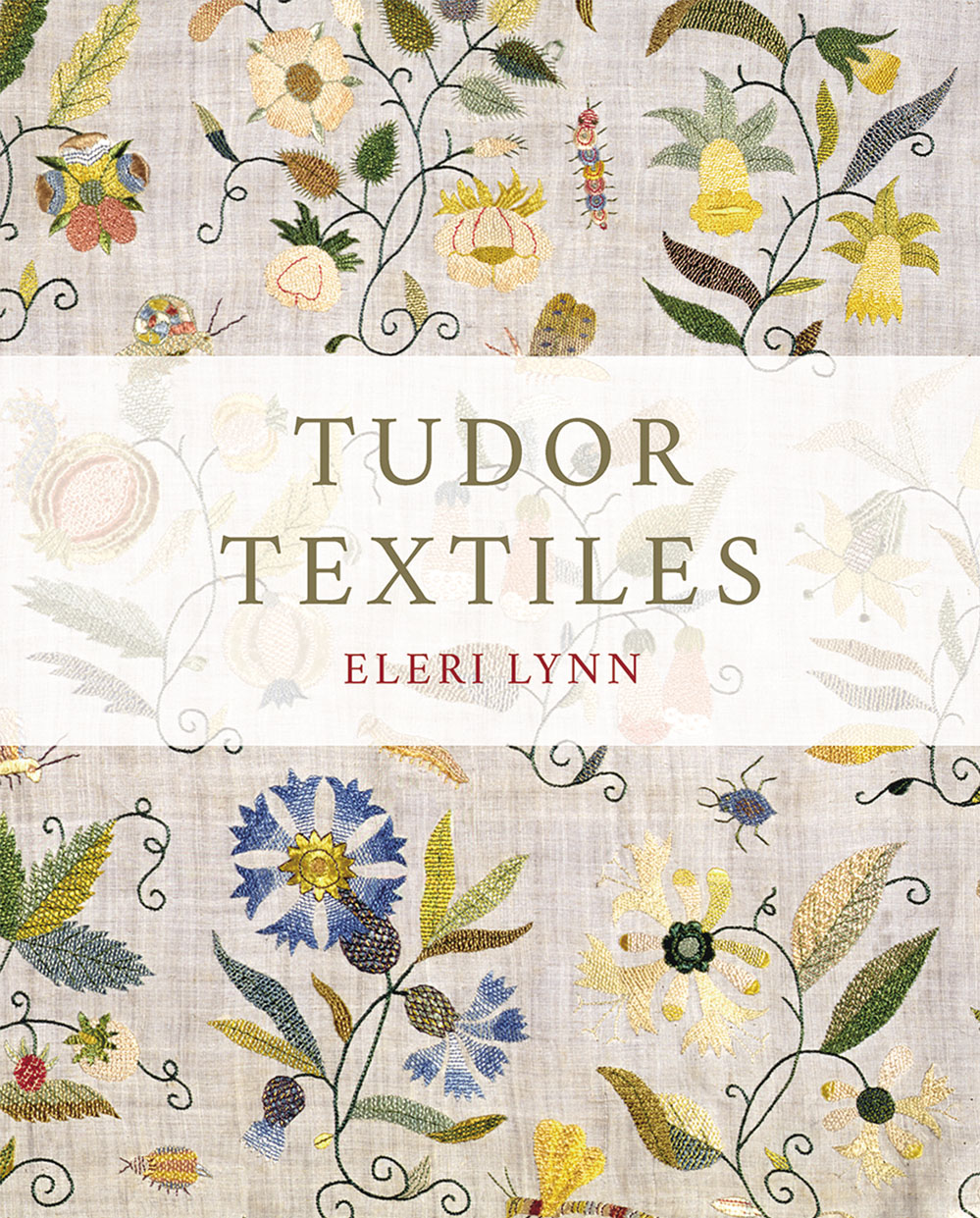

The book’s stated remit is to cover the wider role of textiles at court, rather than details of materials and techniques. The long century encompassed by the book means that a lot of the information presented is necessarily general. But Lynn’s story is by no means under-researched or lightly wrought. Her scholarship is evident not only in what she has included, but equally in what she has left out to ensure the book is fit for a non-specialist audience. The result is still full of detail and evidence that may not have been drawn together in a book before. Tudor Textiles is not comparable to the forensic dive that is a book like Janet Arnold’s Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Unlock’d. Yet neither is it so light that will not have something to offer textile specialists.

The armorial binding of Martin de Brion’s description of the Holy Land, dedicated to Henry VIII, England, ca. 1540. Purple velvet embroidered with silk and metal thread and pearls. British Library, London, Royal MS 20 A IV

Tudor Textiles, then, is a broadly writ story of elite textiles that were commissioned by and on behalf of the ruling head of the country during a rich and tempestuous century. The relationships, business and personal, that governed the export and import of Tudor textiles is backgrounded thoroughly in this book, so much so that it would happily sit somewhere between social history and textile history on the library shelves. Many people made a living through and with textiles in the Tudor period—from the shepherds and silkworm farmers, to the weavers, dyers, finishers, through to all the many figures at court who dealt in commissions and transactions to bring the best of the world’s textiles to the English court.

The administration of textiles (after they had reached court) was detailed and specific. Textiles were kept in the Great Wardrobe, a department under the Privy Chamber. The Wardrobe ‘ordered, paid for, managed and maintained the stocks of cloth, dress and furnishings for the royal family and the court’. Then there were the many men needed to service textiles—to hand, for example, the king his napery: ‘First, the king washed his hands and dried them with a linen towel. The towel was passed from the gentleman usher to the “prince or lord of the highest estate”, while the nobleman of the second highest rank held the basin under the king’s hands. When the towel was returned to the gentleman usher, the part “in which the king hath wiped was carried by the usher above his head”. Once the king was seated at the table, the tablecloth was lifted over his lap. He was given a napkin, and the servant waiting upon him held another on his arm.’ Pomp and ceremony, yes; all centered on textiles.

Valance (detail), England, ca. 1532–6. Light cream silk taffeta with linen canvas backing, decorated with arabesque black silk velvet cutwork motifs of acorns

The shift in textile types during the Tudor period is interesting. In the textiles he commissioned, Henry VIII seemed to have a decided taste for his own aggrandisement: huge tapestries, many in series, picturing heroic deeds. These would have the effect of committing his healthy self-image to both cloth and to history, building his reputation and legacy. Under his daughter, Elizabeth I, embroidery took precedence. And so domestic, naturalistic, small ‘feminine’ textiles take over the book, too, in the form of embroidered book covers and bed linens. Lynn suggests this might be partly because Elizabeth not only inherited Henry VIII’s over-sized collection of textiles, but that she also inherited the debt he incurred, leaving her less able to commission large series of tapestries.

Tent design, probably for the ‘Field of Cloth of Gold’, 16th century. Watercolour on paper. British Library, London, Cotton MS Augustus III, fol. 18

Tudor Textiles is, of necessity, the story of Tudor royalty; the textiles of the common people are not the subject here. As with much decorative art (particularly that which has survived in public collections) the rich and powerful were the people who commissioned textiles of note and beauty. The publication of this book was timed to coincide with the 500th anniversary of the ‘Field of Cloth of Gold’, a meeting between Henry VIII and Francis I of France, in Calais in 1520. A political event built and realised through magnificent textiles, it offered proof, if it were needed, of the predominance of Tudor textiles over all other art forms.

Reviewed by Jane Audas

Comments [0] Sign in to comment