HALI Profile: Jenny Housego

Author, collector and textile entrepreneur Jenny Housego has had a remarkable life, which is now told in full in a new book. In HALI 204, she talks to us about some of the landmark moments in her career.

It was while walking through the textile galleries of the Victoria and Albert Museum that Jenny Ormond (as she then was) felt the first stirrings of a taste for adventure. She had studied Early Christian Art before taking up a job at the museum, her main interest being in ceramics. A transfer to the textile department, about which she was initially dubious, introduced her to Dr May Beattie, in Jenny’s opinion ‘the greatest authority on carpets of her time. She was my mentor and passed her fascination for carpets directly onto me’.

The technical processes of textile production were central to May Beattie’s scholarship, and Jenny was quick to adopt the same approach. ‘I was among the few scholars at the time who had studied this,’ she says, ‘and it was all thanks to May Beattie. During my travels in Iran I was able to look carefully at what type of knot had been used, how many wefts, and what the twist was. Answers to these could give a fairly clear idea of origin. Even today I find it difficult to just look at a textile without getting into the depths of how it was made.’

In 1969, shortly after marrying David Housego, a journalist with The Times, Jenny moved to Tehran. There her interest shifted away from the classical-period carpets that were Dr Beattie’s speciality and gravitated towards tribal weavings. ‘In the early days it was impossible for us to afford classical carpets. Close to our house there were numerous shops selling every kind of rug, with bold, usually geometric designs and bright colours. I suppose that these reminded us of the modern paintings which we had started to collect in London in the 1960s. Thus our love for these tribal rugs was implanted.’

Soon the couple were venturing away from the Iranian capital. ‘I wanted to learn more about these tribes. My research led me to the discovery of the Shahsavan nomads of northern Iran, so one day we set off to Ardebil, at the foot of mount Savalan. There we hired ponies and a guide to take us up the steep slopes to the summer pastures of the tribe. By the time we got there, several tents made of tightly woven goats’ hair had already been put up. The occupants were surprised but welcoming, and we were immediately offered tea. It was very rare for foreigners to visit them, after all.

‘I was fascinated with the colourful clothing the ladies wore. We saw one saddlebag which was so beautiful, it made us gasp! It took a lot of persuasion for them to finally sell it to us, and it has remained a treasured piece ever since.

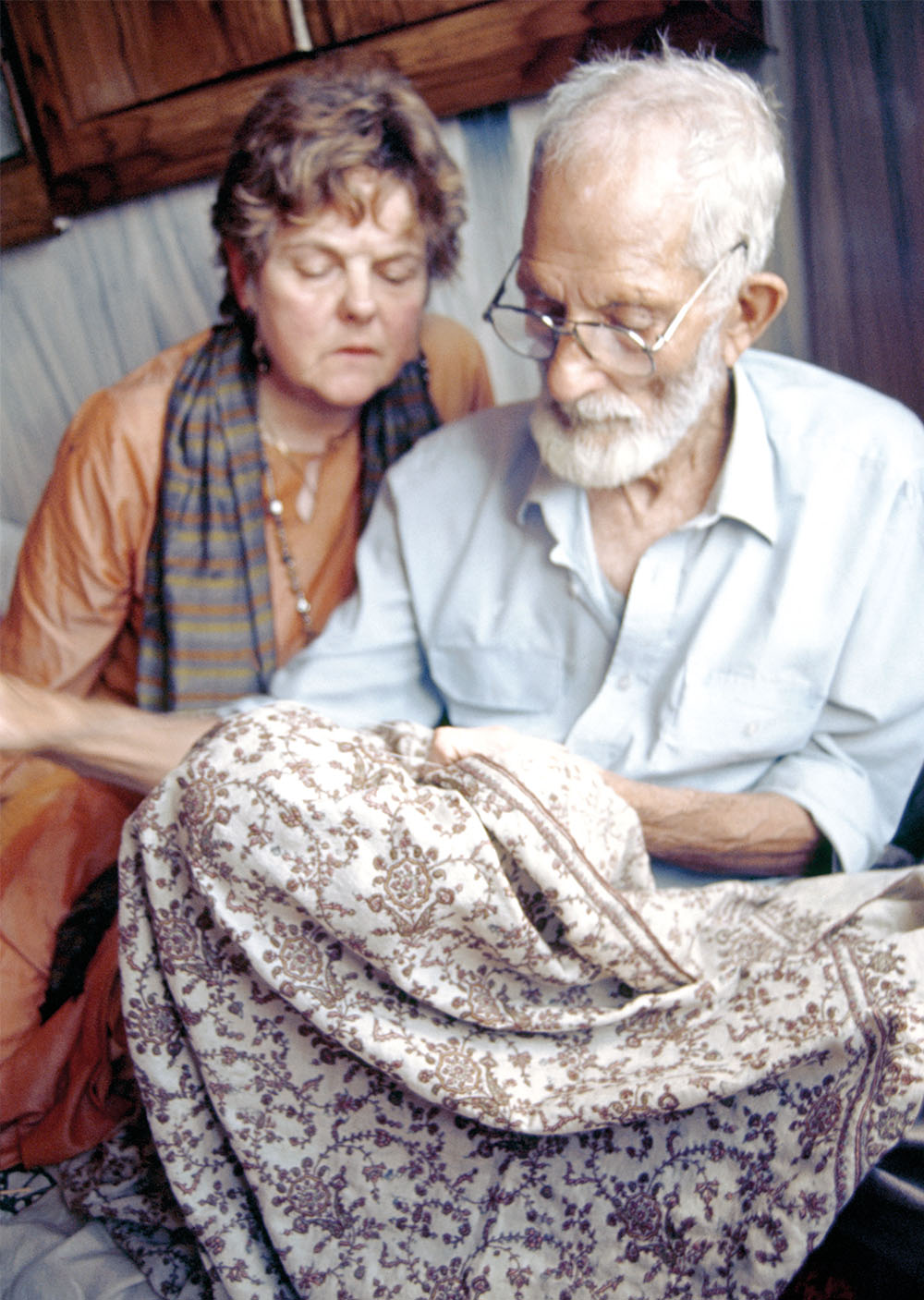

Jenny deep in conversation with David Reisbord, who invited Jenny and her colleague Asaf for tea to look over his collection of vintage shawls after Jenny’s lecture at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

‘On another occasion we went to Shiraz, in the south of Iran. We pitched our tent near a tribe just setting up their tents in their summer pastures, who turned out to be Lurs, who we had been told were a dangerous lot. But soon a messenger came and said we must move our tent next to theirs. We were invited to the tent of the chief, who had heavily armed tribesman all around him. He explained that he had insisted that we move closer to him, to be able to protect us! He gave us dinner, but I have completely forgotten what it was except that it was tough and oily.’

At the time tribal weavings still attracted the interest of only a handful of enthusiasts. But Jenny and her fellow collectors made an effort to change perceptions. ‘Parviz Tanavoli, John Wertime and I were instrumental in setting up the Tehran Rug and Textile Society, as I think it was called then,’ Jenny says. ‘We all pooled our collections together to do the exhibitions. They were a great success, provoking so much interest. Many Iranians also became collectors. There was one particular shop in the main carpet bazaar which was owned by Yeusef Bolour—he always had the best new finds. At first we had him to ourselves, but all too soon we had to fight with other Rug Society members to get the best pieces.’

Jenny and one of her greatest inspirations when she had just started working with craftpersons in Kashmir Valley—Phalguru, the renowned sozni embroiderer

In the mid-1970s the Housegos moved back to Britain, which remained their base for a decade. But it was India that thereafter became their permanent home. ‘When we first came to Delhi, carpet dealers flocked to see us. None of them had anything of the artistic quality of those we knew from Iran. Soon enough they found out that I was not just an expat in Delhi looking for rugs, but a wellknown expert in carpets.

‘I had met Ann Shanker in London and was reconnected with her when I got to India. She was living in Punjab, where she had seen the most extraordinary dhurries, tapestry-woven cotton. She asked me if I would be interested in joining her in a project to document these textiles in the villages of Punjab. I jumped at the idea! I had done no fieldwork for ages, and to find it lying on my doorstep in India was absolutely wonderful.’ The result was her book Bridal Dhurries of India.

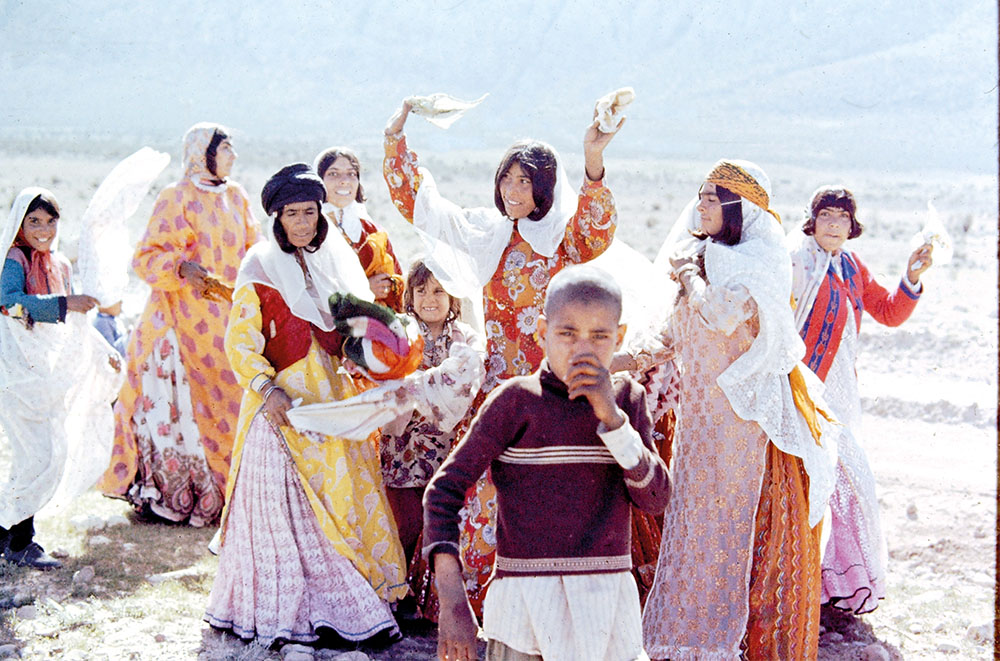

A wedding procession of a Qashgha’i family in Fars, southern Iran. Jenny remembers them crossing the road and, when her car stopped for the procession to pass, in no time many from the procession, including the bride, bundled into the back of her car for a ride

During her time in the subcontinent, Jenny has witnessed a tremendous revival of craft traditions. ‘The perception of Indian handicrafts when I arrived was cheap and cheerful. Now, they enjoy admiration and respect around the world. Indian craft is the biggest source of income for the country and is flourishing. More work and encouragement is needed, but I see a bright future.’

Jenny has played an active role in this process of renewal. In 1995— shortly after a traumatic episode in which the Housegos’ son, Kim, was kidnapped by militant Islamists but eventually safely returned— the couple set up their own textile manufacturing business. ‘Shades of India was one of the pioneering craft-based companies which took Indian-made products to the international stage. For our first collections we translated traditional work used for dupattas and saris into beautiful home furnishings on crisp cotton organdie.’

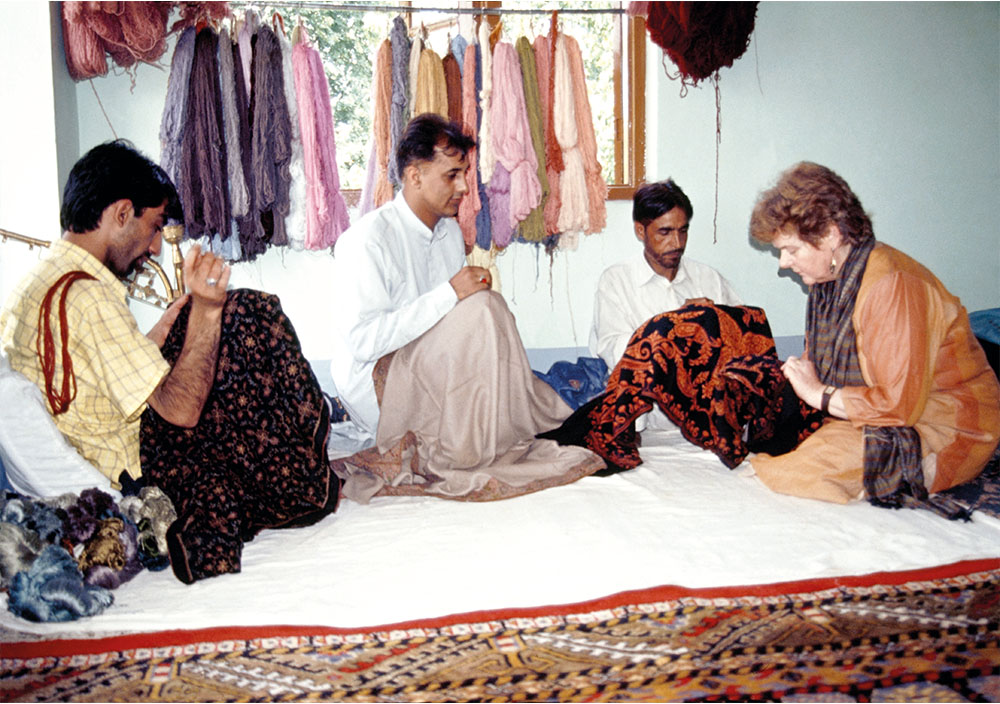

At the beginning of the 2000s, David and Jenny’s marriage had come to an end, but she had started up her own, new company: Kashmir Loom. ‘Antique shawls became the inspiration and guide for our collections,’ says Jenny. ‘Careful study of their techniques and construction showed us how to develop and revive of some of the best work which had been done in the region.

‘Having had many years of experience working with craft and artisans in many parts of the world I was able to infuse great enthusiasm into the weavers in Kashmir. It was not always easy because I was a complete outsider, but I persevered and slowly began to gain their trust and even their affection.’

A Woven Life by Jenny Housego with Maya Mirchandani is published by Roli Books

The Jenny I know

I met Jenny about seven years ago, when I walked into the Kashmir Loom store in Delhi. She is delightful, witty and totally no-nonsense. She loves company, never tires of hearing other people’s stories, and has plenty to tell herself. It’s a wonderful gift.

She has a tremendous skill in her ability to blend ‘eastern’ motifs and designs with a ‘western’ palette of colours. She understands intuitively what works and what doesn’t, but she’s always as happy to learn and take in suggestions from others as she is to teach what she knows.

Her need for perfection is often at odds with what is going on around her, and I could relate to that. She’s vulnerable, but I find that in Jenny her inhibitions have made her stronger. Her determination and resilience, her will to survive and contribute to the arts, to business, to improving the lives of others, is worthy of tremendous admiration.

Maya Mirchandani, with whom Jenny Housego wrote A Woven Life

Comments [0] Sign in to comment