How the Dutch Made Chintz Their Own

Nathalie Cassée has uncovered documentation that rewrites the accepted history of block-printing cotton in Europe. In HALI 205, she explains why she believes that the Netherlands city of Amersfoort is the industry’s true cradle.

For a long time it has been widely accepted that the first block-print workshop in Europe was established in England in 1676. My research shows that this is based on incorrectly interpreted archival information. In fact the first documented attempt to introduce cotton printing in Europe took place in Amersfoort in the Netherlands. It was the Dutch East India Company (VOC) that brought chintz and the art of cotton printing from India to the Netherlands. In Europe, just as with spices, these would prove to be highly lucrative acquisitions. Chintz has thus been part of the Dutch heritage since the 17th century. In the mid-17th century, such pieces were mainly used by Europeans as luxurious home textiles, but were also adopted into the clothing fashions of the day. It was mainly the upper classes who could afford Indian chintz, and they had it made to their own taste in India. Later in the Netherlands, discarded fragments found their way to the common man and were incorporated into regional costume.

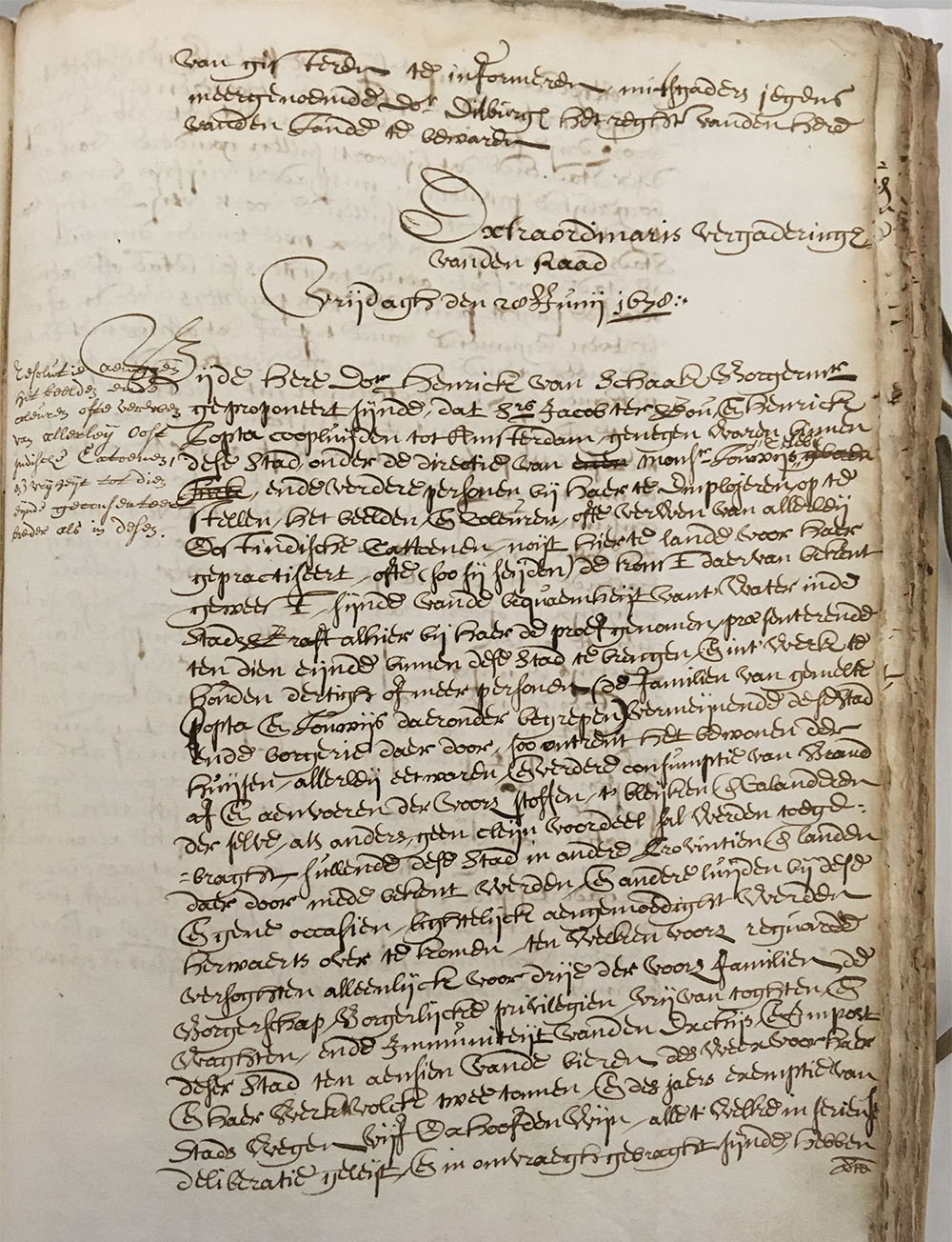

City resolution from 1678: the council of Amersfoort grants the settlement of the first block-print workshop in the town. © Archief Eemland/Nathalie Cassée

Transport via ships going back-and-forth to the east was a time-consuming and costly undertaking. Unsurprisingly, entrepreneurs soon began experimenting with this printing technique in Europe. There was considerable investment in their efforts, but only a few mastered the skill to successfully print with natural dyes, and secrecy was often enforced. Besides that, in Europe there was a lack of the necessary solar heat to enhance the development and fixation of natural dyes.

In the spring of 1678, two VOC merchants from Amsterdam, Jacob ter Gou and Henrick Popta, set up a block-printing workshop in the city of Amersfoort, northwest of Utrecht, together with a man called Louis d’Celebi, most likely an Armenian. Amsterdam was home to a significant Armenian community at that time. In the city records relating to their proposal of the project, we read that they ‘want to establish a workshop for imaging, colouring and dyeing all kinds of East Indian cotton, which has never happened in the Netherlands before’. They had tested the city water and were proposing to settle there. Their arguments seem convincing: ‘They believe that this will result in new business and income for the city… As a result, the city will become more important nationally and internationally, which in turn will attract new business.’

The city council unanimously decided to grant citizenship to the three families and to exempt them from all local guard and excise duties. Later archival documents plausibly suggest that they did indeed set up the workshop. In September 1678, Ter Gou and Popta applied for exemption from paying tax on their freight; eight months later, in May 1679, they requested control over and exclusive rights to print chintzes in and around the city. Given the popularity of chintz, they apparently feared competition.

The question now is why Amersfoort was chosen for setting up this enterprise. Was the deciding factor the clean and mineral-rich waters from the Veluwe valley? Or did connections within the VOC play a role? Pieter van Dam, born in Amersfoort and the son of mayor Willem van Dam, was an influential advocate general of the VOC for fifty-four years. The founder of the VOC, Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, was also born in Amersfoort.

Was it the flourishing textile industry, meaning that extensive facilities and experienced craftsmen were readily available in the city? Since the 15th century Amersfoort had accommodated an important textile industry. For centuries the city council had an active recruitment policy, granting exemptions and privileges to textile entrepreneurs who wanted to start a business. Did the presence of indigo dyers play a role? These unanswered questions beg further historical research.

Not long after the first block-print workshop began operating in Amersfoort, other factories were founded, mainly in Amsterdam. At its height, in the mid-18th century, Amsterdam had as many as eighty printing houses, especially on the street called Overtoom. Designs from these ‘Overtoomse Drukkerijen’ have recently been found in the archives of the University of Amsterdam.

From the end of the 18th century, manual printing came under pressure due to foreign competition and innovations such as roller printers. Nevertheless, a large number of still-extant companies emerged from the former block-print companies, such as the Dutch SHV Holdings (Vlisco), French DMC yarns, and several chemical companies. The continuing importance of chintz is also reflected in the interest it receives from museums all over the world. In October 2020, block-printing returns to Amersfoort with the opening of De Katoendrukkerij in the old textile mill the Volmolen. A more suitable place could not have been chosen, since the building is a symbol of the textile heritage of the town.

Comments [0] Sign in to comment