Book Review: Indian Tiles

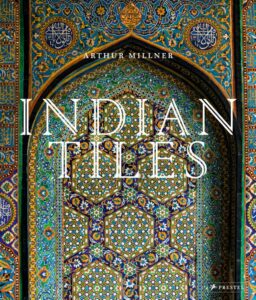

Featured in HALI 210, Penny Oakley reviews Arthur Millner’s latest book, Indian Tiles: Architectural Ceramics from Sultanate and Mughal India and Pakistan:

Arthur Millner’s first book, Damascus Tiles, addressed a topic never before studied in its entirety (reviewed HALI 186). It became one of those works that establish themselves as the encyclopaedia for their field. His new monograph, Indian Tiles, was an even more daunting project, given the vast territory it covers and the variety of cultures and religious creeds involved. As an old India hand with long experience of the region and its artistic heritage, he is well equipped to tackle such a colossal task, but it is still not one for the faint-hearted.

In their glory days, India’s monuments were glittering testaments to the riches, power and often vanity of their creators. Millner mourns the now-fading splendours of their tiles, as so many have succumbed to the climate, neglect or pilfering, or have been plastered over, while others have now vanished completely. Lack of money and interest are factors. Another is the current siting of Hindu buildings in Pakistan, and Muslim ones in India, which presents certain impediments to their being cherished and protected. Just as Damascus tiles are often seen as the poor relations of Iznik, the arts of India were, until not so long ago, regarded as secondary to those of Persia, with many Indian objects wrongly called Iranian. But now India has come into her own, as proved by recent scholarly works and high auction prices. This book may be a paean to the skill and virtuosity of Indian tile painters and cutters but it discusses, too, the history and tile products of each relevant region and regime. Also included are good international, regional and city maps pinpointing the relevant sites—a rare bonus.

The introduction contains descriptions of the materials, glazes and pigments alongside the manufacturing and decorative techniques. In the pages that follow, the most striking feature is the outstanding quality of the photographs, and their quantity (over 400). Many are by the author himself. There are full-page spreads with powerful, in-your-face images of entire buildings. The finale is the ‘catalogue’, an anthology with details from tiled revetments in situ, plus individual examples from worldwide collections, which must have been quite a marathon in itself to collate. No less welcome is a glossary of terms, followed by the customary notes and bibliography.

Any mention of India evokes images of the Mughal dynasty, but her tile culture began long before, with the most exceptional examples being the prowling tiger and waddling duck friezes in the Man Mandir, in Gwalior, built circa 1500 (pp.177–79, figs.4.60–64). Even in the Mughal period, the Indian subcontinent was a patchwork of independent states, each with its own artistic tradition evolving in its own way, despite varying degrees of Mughal influence. Not only the designs, but also the colours vary widely, from the simple blue, white and turquoise of Sindh to the myriad shades of the Mughals. Thus the decorative range is immense, ranging from the simple border in Orchha, complete with lounging monkey (below) (pp.184–85, fig.4.71), to the complex cut-tile mosaics executed with great skill and virtuosity in Bidar (1) (p.150, fig.4.18). This arch has the same, probably also Timurid-derived, flower with crossed sepals that occurs on some central Anatolian rugs and Ottoman court kilims.

Under the Mughals a triangular relationship, both cultural and commercial, existed between India, Persia and Central Asia. The latter arose because Babur, the founder of the Mughal dynasty, was the Timurid prince of Andijan, in the Ferghana Valley, now in Uzbekistan. His descendants never forgot this connection, and did much to maintain and promote trade and cultural interaction. Indeed, some 19th-century Uzbek suzanis have floral motifs similar to those on Indian tiles (p.250, cat.46; p.256, cat.68).

A cut-tile niche in the Badshahi Ashurkhana, Hyderabad, Deccan (built circa 1612), has monumental strapwork borders and other details similar to many Safavid carpet designs (cover and p.27, fig.19). It is a manifestation of the constant brain-drain of artists from Persia and Central Asia to India, and demonstrates how her designers absorbed imported influences to create new styles that were uniquely and unmistakably Indian.

With its magnificent artistic heritage, India is so photogenic that the author has successfully created a banquet for the mind and eye of scholar and student alike, and pure caviar for the armchair traveller.

Comments [0] Sign in to comment