Profile: Fred Mushkat

The new book from American collector Fred Mushkat is the first publication to concentrate fully on the woven bands of nomads. He tells HALI how he approached filling a significant gap in textile literature.

Fred Mushkat and his family moved to different cities as ‘part of the adventure of life’. Before his retirement in 2018, Fred had a forty-year career as an emergency physician with no permanent office or staff. But, as is conventional in the US, his medical school training was rounded off with a ‘residency’ period, which was the first time he had earned a salary. He began searching yard sales for items to furnish an apartment.

‘After a modest acquisition of a Caucasian rug, I took it to Richard Markarian, the Armenian rug dealer, to learn about what I had just purchased. It was in his gallery that I had my first exposure to village weavings and the textiles made by nomads. I was entranced by the rich motifs, colours and materials and decided that weavings by nomads spoke to me more than village workshop or city rugs.’

His specialisation in woven bands came after he met John Wertime, ‘whom I knew from HALI to be an expert on weavings by nomads in Iran. On my first encounter with John, I bought a saltbag and forged a relationship with him. After a few more purchases, including a Shahsevan sumakh bag, John showed me a few Qashqa’i bands along with a Kurdish band from Anatolia. I immediately felt that these were exactly the type of weaving for which I had been searching.

Collecting bands was possible because it was an unrecognised market with virtually no competition among collectors.’

Shahsevan pack-animal band, Iran. Fred Mushkat collection. Published in Weavings of Nomads in Iran, no.86

From the very beginning Fred recognised the importance of these textiles as part of the cultural heritage of the nomads who made them. ‘I felt that I was merely the current caretaker. From my perspective the first step as a collector was to provide for the safekeeping of the collection for future generations. I knew little about this but learned through membership at the Textile Museum in Washington, D.C.’

‘I realised that my next role as caretaker was to share what little I knew with other collectors. I began giving talks to groups of interested parties. As the number of bands in the collection and my knowledge about them increased, I felt that I had an obligation to add what I knew to the literature because there was so little published. This became my most important role as a collector.’ Weavings of Nomads in Iran: Warpfaced Bands and Related Textiles (Hali Publications Ltd., 2020) is indeed groundbreaking in its sharp focus and in its publishing of a plethora of handwoven bands for the first time.

Qashqa’i pack-animal band, Iran. Fred Mushkat collection. Published in Weavings of Nomads in Iran, no. 35

‘Before I began writing about bands,’ says Fred, ‘I read every back issue of HALI and every book I could find to improve my knowledge base. With my background in science, I felt that if I were to state the meaning of a motif—unless it was obvious, like a flower on a stem—then I needed to have credible information to support that opinion. As westerners, most of us have no idea what these images meant to the weaver a century earlier.’

‘I had the good fortune to visit Peter and Mügül Andrews in 2007, who shared with me some of their fieldwork in Iran regarding design names. My knowledge increased even more dramatically when I began discussing bands with Lois Beck, who had spent decades studying and living among Qashqa’i nomads. Dr Beck then introduced me to Naheed Dareshuri, a Qashqa’i expatriate who grew up as a nomadic pastoralist and became an expert weaver. Finally I had the good fortune to learn from the source.’

Fred admits to initial disappointment when he learnt from his associates that the designs were unlikely to contain hidden messages. ‘Dr Beck pointed out to me that many designs were ones that worked on the loom and were pleasing to the weaver and never had any meaning beyond that.’ But acceptance of that reality has enabled him to avoid the pitfalls of mystical speculation that beset many scholarly collectors.

Another potential minefield is the question of dating. ‘In my text I listed a number of ways in which the age of a weaving can be determined,’ he says. ‘There have been some collectors who wanted their pieces to have great age and some dealers who inflated the age to make it more desirable to purchase. Without any scientific approach or fieldwork to back up such an assertion, it became guesswork, although rarely stated as such. My approach has been to make it clear to the reader that a design may be a snake, for example, instead of affirming that it is a snake. Likewise, I say a weaving may be from the 19th century rather than it is definitely a 19th-century weaving.’

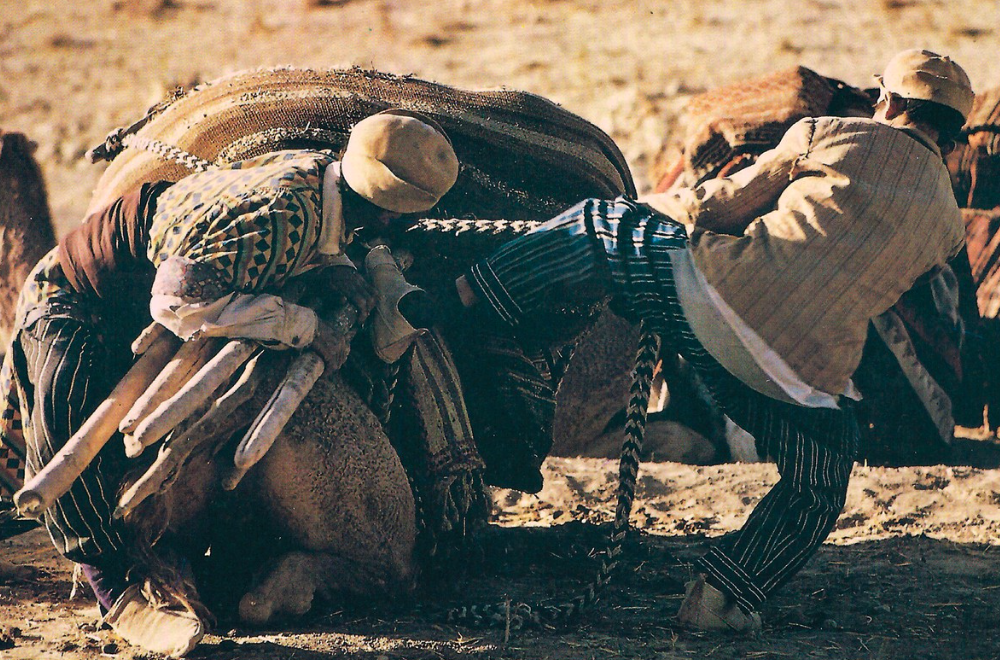

Qashqa’i men loading a camel in preparation for migrating. Photographer and year unknown. After Manuchehr Kiyani, Migrating with the Love of Anemone (Such ba eshq-eshaqayeq), Shiraz, 1999, 205

‘Ultimately, the purpose for publishing the book was to get an important aspect of the material culture of nomadic pastoralists in Iran into print in order to help preserve the textiles and their beauty for present and future generations. Although this seems like a lofty goal, it is what drove me to completion.’

‘I believe we are seeing a trend away from apocryphal writing in all areas of the weaving traditions of Asia and the Middle East. Improved scholarship is the only path to add meaningfully to the material culture of these weavers. Future writers should also be on the lookout for areas in which scholarship is missing. Focused books have the potential to cover more ground and help us understand the field of textile studies.’

Fred’s advice to the next generation of textile scholars and collectors may have an idealistic ring to it, but he is willing to give advice at the most practical level. In addition to advocating extensive reading on and around the chosen subject, he recommends taking close-up photos of the details of a piece. ‘By isolating the separate designs, it allows the collector to focus on just that single image or part of a weaving and learn how it adds to the overall scheme. Studying an isolated part will almost certainly enhance one’s appreciation of the whole.’

It should be clear by now that Fred Mushkat takes his responsibilities as a collector and writer as seriously as he must have taken the issues in his medical practice. His concern for consequences extends to the effect that Weavings of Nomads in Iran might have even beyond its readership. ‘After meeting Naheed,’ he says, ‘I realised that the book may have an impact upon present-day Qashqa’i nomads and help preserve a vanishing art form. Other collector/scholars can and should take a similar approach—as the holders of this cultural information we owe it to these weavers to promote their art.’

Comments [0] Sign in to comment