Textile art in San Francisco

The Tribal & Textile Art Show in San Francisco

19 images

The view from the floor of the Tribal & Textile Art Show in San Francisco, which opened its doors on 9-11 February 2107 at Fort Mason in the Marina District.

- Zeikhur rug (detail), northeast Caucasus, 19th century. Hagop Manoyan, New York

- Ben Benayan who helped Peter Pap catalogue and mount his exhibition Artful Weavings at The Tribal & Textile Art Show

- Complete Shahsavan sumakh khorjin, 19th century, Caucasus. Sold by Peter Pap as part of the exhibition, Artful Weavings, collection of Mr. and Mrs. Wendel Swan

- Bruce Baganz, chair of the Trustee of the Textile Museum at George Washington University, ,awards gallerist Mehmet Cetinkaya from Istanbul the Joseph V. McMullan Award for Stewardship and Scholarship in Islamic Rugs and Textiles, which is presented annually by The Near Eastern Art Research Center

- Peter Pap’s exhibition Artful Weavings at The Tribal & Textile Art Show

- One half of the new owners of the Tribal & Textile Art Show, John Morris of Objects of Art Shows.

- Kuba bagface, northeast Caucasus, 19th century. Offered by Peter Pap as part of the exhibition, Artful Weavings, cMr and Mrs Bruce Baganz collection

- Dated and inscribed Qashqa’i kilim, southwest Persia, 19th century. Jack Corwin collection offered by Peter Pap as part of the exhibition, Artful Weavings

- Batik artist using wax resist on cotton batik – part of the display of exhibition of Indonesian textiles from The Jakarta Textile Museum organised at The fair by Curtis and Margaret Keith Clemson

- An antique hanging from Bhutan made up from 5 panels of Indian-Assamese Vaishnavaite silks, so-called Vrindavani Vastra, 17th-18th century 369 x 163 cm. Plum Blossoms, Hong Kong,

- Malatya kilim fragment, east Anatolia, 18th century. Anatolian Picker

- Ali Osman Aykul aka Anatolian Picker, Istanbul

- George Postrozny of Tahoe Rugs exhibited Native American weavings

- Kain panjang (detail), Surakarta, Java, Indonesia, 20th century. Jakarta Textile Museum, gift of Pakubuwana XII

- Local textile specialist Andres Moraga stand included an exceptional Sierra Leone strip woven blanket from the 19th century amongst the Central African fibre works for which he amongst the world leaders.

- Boujad rug detail, 20th century, Middle Atlas. Gebhart Blazek, Graz, Austria

- Sante Fe textile specialist John Ruddy showing a client a Javanese batik

- Deccani (?) carpet fragment, 18th century, India. Plum Blossoms, Hong Kong

- Luri gabbeh, west Persia, late 19th century. Jack Corwin collection offered by Peter Pap as part of the exhibition, Artful Weavings

On entering the Tribal & Textile Show at Fort Mason this February, it seemed that everything had changed but stayed the same. Although the show has been sold by Liz Lees to Kim Martindale and John Morris (Objects of Art LLC), producers of five other US art shows, I was still met at the door by Liz and the same friendly faces associated with the fair for many years. The special exhibition, this year of Indonesian textiles, was hanging in the foyer, and the stand design and floor layout seemed to be the same.

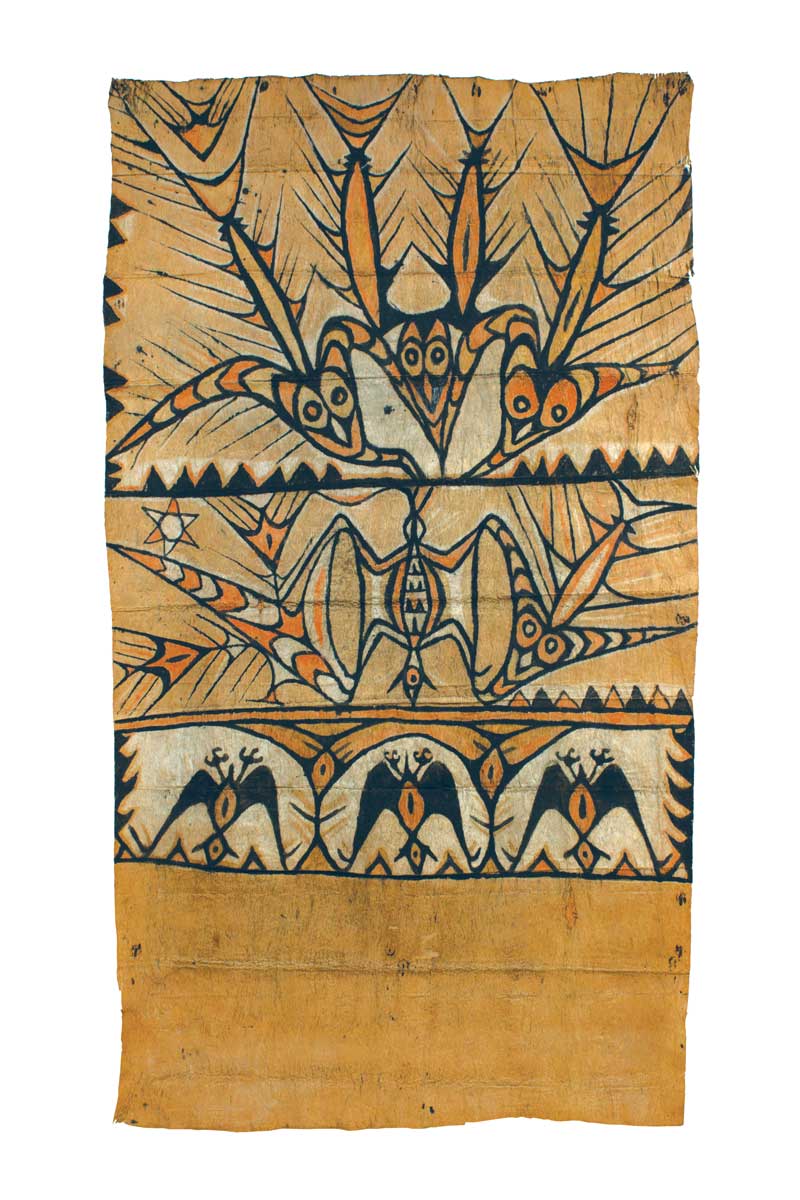

With so much material to see, I tend to find it takes me a bit of time to look past the things that are on display and really look, to realise what is of interest and exceptional and unusual. A case in point was perhaps the most remarkable textile in the show: the Lake Sentani barkcloth offered by Vicki Shiba (1). Michel Thieme wrote a definitive article about this esoteric group of barkcloths in HALI 175 (2013, pp.82-89), which began with a quote that describes well my sighting across the hall: ‘There is nothing that can be said about these tapa… save that they exceed all normal bounds. They present the signs of a writing so subtle, so spiritual, so abstract that the mind suffers a shock.’

Lake Sentani tapa cloth maro, northwest New Guinea, early 20th century. Barkcloth, natural dyes, pigment, 1.16 x 0.70 m (3′ 9″x 2′ 3″). Vicki Shiba, Mill Valley, California

The best textile art has an aesthetic impact that is greater than its physical dimensions. While the New Guinea maro may be one case in point, this may be best illustrated by the Fez belt displayed by Gebhart Blazek (4). Small and long, on a wall this textile does not draw one in across a room, but the dynamism and modernity of the design and the confident transition between bold patterns and colours are undeniable. This is one of the best of these fascinating lampas-woven silks that has been on the market for some years—a brilliant and surprising illustration of the sophistication of Muslim women’s fashion from the early 18th century. It deserves to be in a museum.

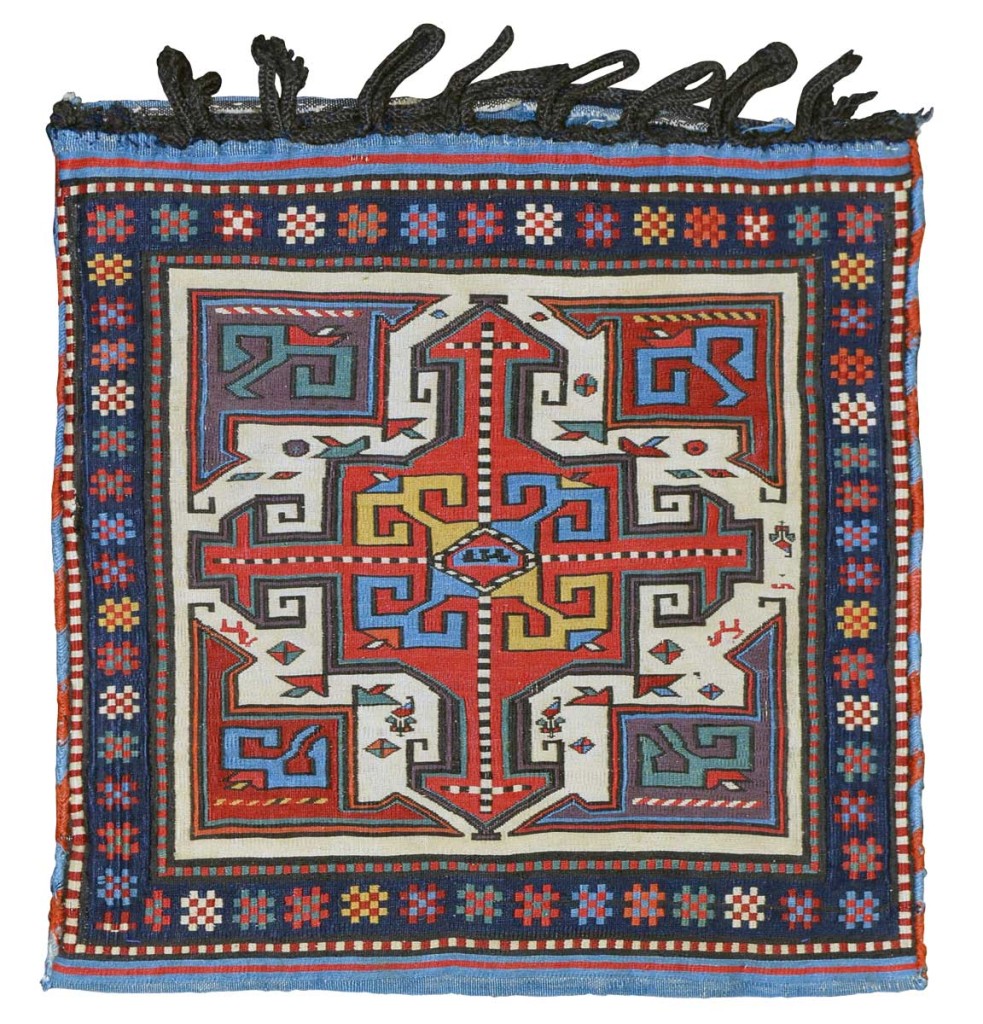

With well over one hundred pieces, Peter Pap and Ben Benayan created a show within a show, of great value to the fair and to the rug community locally. This was not an act of pure generosity as there were several significant sales made throughout the fair, mostly of the best of the bag faces, and mostly benefitting Wendel Swan, whose two iconic Shahsavan sumakh bags sold for a total of more than $80,000—a figure that should draw serious attention to the successful ‘deaccessioning’ service that Pap has established. I had not seen the cruciform bag (2) in the flesh before but was shocked by its crisp condition: it seems as if it has never been used as the colours are bright and the wool has the silky quality you only see with wool that has age but that has not been subject to any significant friction or use. That the same buyer bought both bags is not a surprise as they have been much published and jealously feted when unavailable.

Shahsavan sumakh bag, northwest Persia, Moghan-Savalan region, 19th century. 0.51 m (1′ 8″) square. Wendel R. Swan Collection, Peter Pap, San Francisco

One of the central themes of the fair this year was Indonesia and its textile traditions, centered around the foyer exhibition ‘Indonesian Textile Treasures, A Living Legacy’ organised by Curtis and Margaret Keith Clemson of Dancing Threads in New Mexico. It included pieces such as a batik breast wrapper on loan from the Textile Museum of Jakarta (5), as well as pieces for sale to show the depth and diversity of the archipelago’s textile culture. This exhibition of course was a theme that played into the hands of the world’s leading dealer and expert in Javanese batik, Rudolf Smend, who had an outstanding display of batiks and even had a piece (a donation) in the Jakarta Textile Museum display.

Batik kemben, central Java, Indonesia, 20th century. 0.51 x 2.81 m (1′ 8″ x 9′ 3″). Textile Museum, Jakarta, Gift of Rudolf Smend

Attendance is reported to be about the same as a few years ago and the lecture programme was a great addition to the show and drew good numbers of people. However, even with a greatly increased promotional spend, the profile of most visitors and buyers was much the same as in past years, while the dealers want access to new buyers and to attract a new, younger audience. This is a persistent refrain or problem in the antiques and non-western art field, and it cannot be the job of just this one fair to crack this hard nut. It is clear that the show provides solid foundations for building a wider awareness and appreciation of non-western art, and it is up to all of those involved in the business to find ways to do this—together.

Comments [0] Sign in to comment