Anatomy of an Object: Ushak Coupled-column Prayer Rug

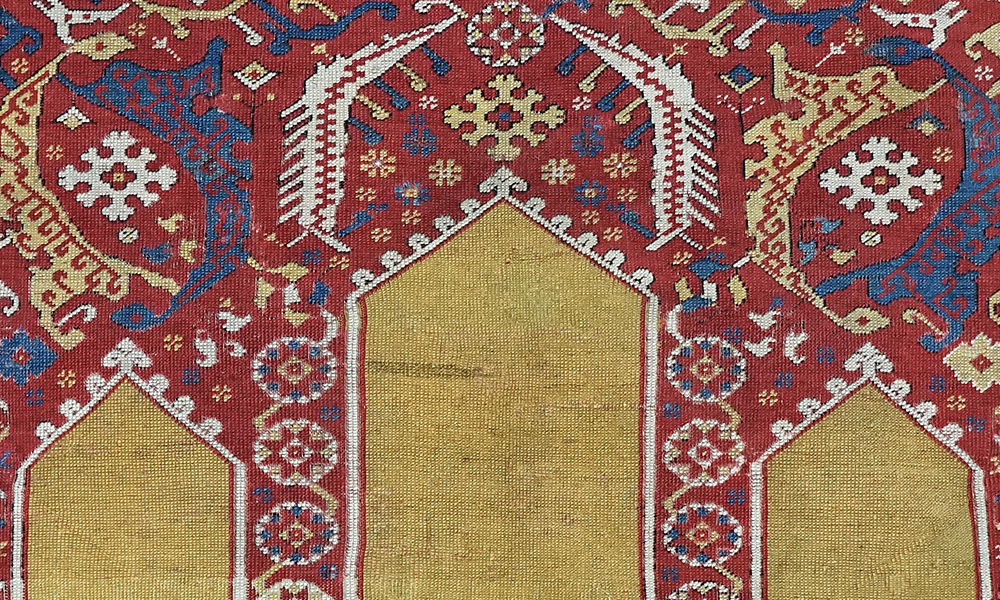

Contributing editor Alberto Boralevi reflects on a rare yellow-ground early ‘Transylvanian’ west Anatolian Ottoman niche rug with six architectural columns supporting curved leaf and rosette spandrels.

Transylvanian’ coupled-column prayer rug, Ushak region, west Anatolia, early 17th century. 1.30 x 1.83 m (4′ 3″ x 6′ 0″). Warp: natural ivory wool, spun Z2S, dyed light red at the lower end, slightly depressed; weft: wool, spun Z, two shoots between each row of knots, generally ivory or dyed light red, occasionally light blue; knots: wool, symmetrical (Turkish), ca. 50 vertical x 38 horizontal, average density ca. 1,900/dm2 = ca. 123/in2; colours: (9) ochre yellow, light yellow, pinkish beige, ivory, red, light blue, medium blue, dark blue, dark brown (corroded). Arkas Collection, Izmir

Formerly with the Milanese dealer Davide Halevim, and then with Eberhart Herrmann, this very beautiful niche rug with an ochre yellow ground is an exceptional example of the earliest group of so-called ‘Transylvanian’ coupled-column rugs. With its high knot density, high-quality wool and rich colours, it is clearly a product of the accomplished commercial carpet industry that flourished in Ottoman Turkey during the 16th and 17th centuries, supplying substantial quantities of rugs for export throughout Europe but especially to the churches of the Protestant Saxon communities in Transylvania (modern Romania). The border in particular, with its rounded cartouches containing classical Ottoman tulips, is typical of the ‘Transylvanian’ genre. The ochre yellow background of the tripartite mihrab, instead of the more common red, is very rare. In an exceptionally good state of preservation for its age, the rug still has several centimetres of kilim preserved at both ends and most of the original selvedges. The pile is uniform with only minimal, skillfully executed restoration.

The richly coloured and decorated spandrels above the three-part yellowground niche in this ‘coupled-column’ prayer rug (the term was first used by May H. Beattie in an article of the same name published in Oriental Art, XIV/4, 1968, pp. 243-258), are filled with tw0 varieties of paired curved ragged leaf forms enclosing snowflake rosettes. Those in white create an implied additional gable above the central broad yellow niche, while the blue and yellow Ottoman saz leaves above the lower and slightly narrower flanking subsidiary niches curl back to touch each other, enclosing the rosettes in a manner reminiscent of the herati design seen in Persian carpets. In both instances the stylisation is such that the leaf motifs can be seen as being zoomorphic in nature, perhaps dragon forms. Carefully planned eight-pointed star rosettes and arabesques complete the internal decoration of this elaborate but well-balanced panel

To our knowledge there is only one other yellow-ground coupled-column rug, a fragmentary example missing both horizontal borders in the Bardini Museum, Florence (inv. 808, Boralevi, Oriental Geometries, 1999, pl.25) that features the same design elements, including the distinctive panel above the niche with trefoils and long-stemmed tulips, and the rounded cartouche border. On that rug, however, the sickle leaf and snowflake rosette spandrels are on a blue ground rather than red, as here. Another very similar rug by design, but with a red field and in very poor condition, is preserved in the Black Church in Braşov (inv. 232, Ionescu, Antique Ottoman Rugs in Transylvania, 2005, cat.198). Other known yellow-ground examples with similar ornaments, but slightly different border and field designs and lacking the tulip panel above the niche, include rugs in both the Museum of Applied Arts (Pasztor, Ottoman Turkish Carpets in the Collection of the Budapest Museum of Applied Arts, 2007, no.40) and the Hungarian National Museum in Budapest.

One of the most distinctive features of this highquality Anatolian rug is only really visible from the back—the use of so-called diagonal ‘lazy lines’ that indicate that for whatever reason—perhaps due to the width of the rug, or as a device to strengthen the foundation to avoid uneven tension—the weaver has turned back on herself so that the wefts return without extending the full width of the rug. Lazy lines often demarcate areas where the weft yarns in the foundation of the rug change colour, as here

The stylised Ottoman tulips seen here both in the rounded border cartouches and above the trefoils in the additional panel that appears at the top of the rug, between the red-ground spandrels and the main border, are typical of many fine prayer or niche rugs woven in the 17th and 18th century in western Anatolia in centres such as Ushak, Gördes and Kula, as well as in so-called Ladik rugs from slightly further east, when they can appear at either end (or both ends) of the rug, and are sometimes inverted

Comments [0] Sign in to comment