Vok Collection Selection 2 at Rippon Boswell, Wiesbaden, 12 March 2016

On the eve of the second Rippon Boswell sale of suzanis and kilims from the Ignazio Vok collection, in Wiesbaden on Saturday 12 March 2016, HALI contributing editor Markus Voigt meets one of the most influential collectors in the textile field, who has spent a lifetime assembling beautiful things.

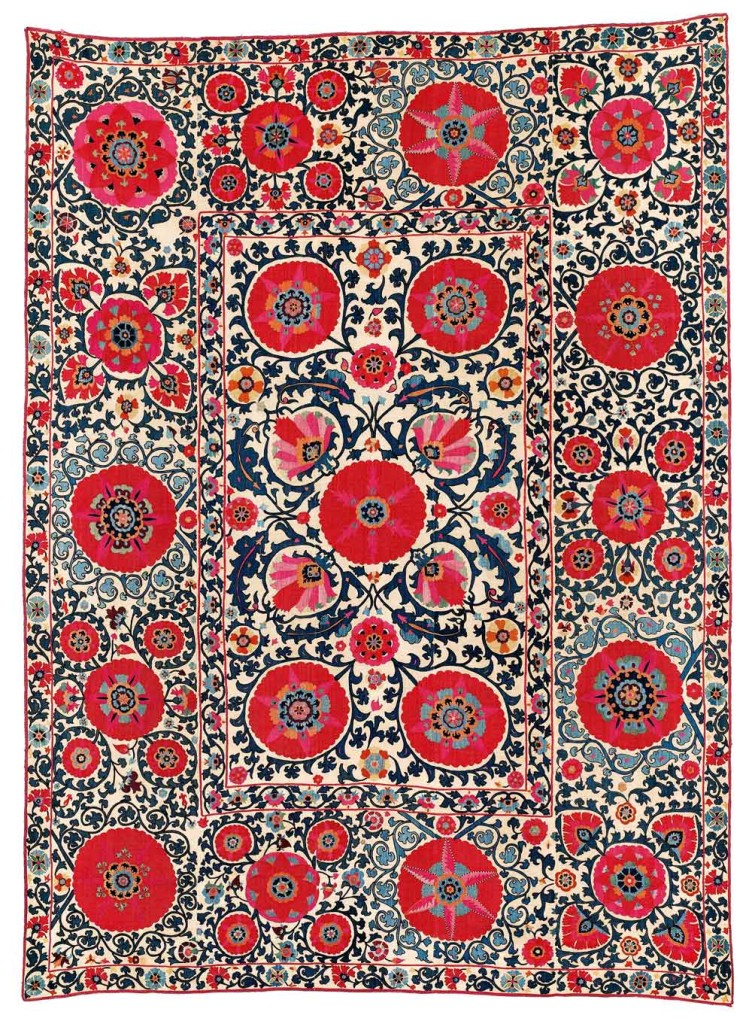

Lot 138. Shahrisyabz suzani, Central Asia, South West Uzbekistan. 282 x 204 cm. ca. 1800. Estimate €40,000 – 45,000

For everyone who had the privilege of being invited to Ignazio Vok’s suzani and kilim exhibitions at Castello di Lispida, near Padua, in the 1990s, they surely rank among the most fantastical carpet and textile events that we ever witnessed. However, as with the suzanis and kilims, Signor Vok has decided to let go of the castle and vineyard, and now lives embedded in his own forest in southern Austria, close to his Slovenian roots.

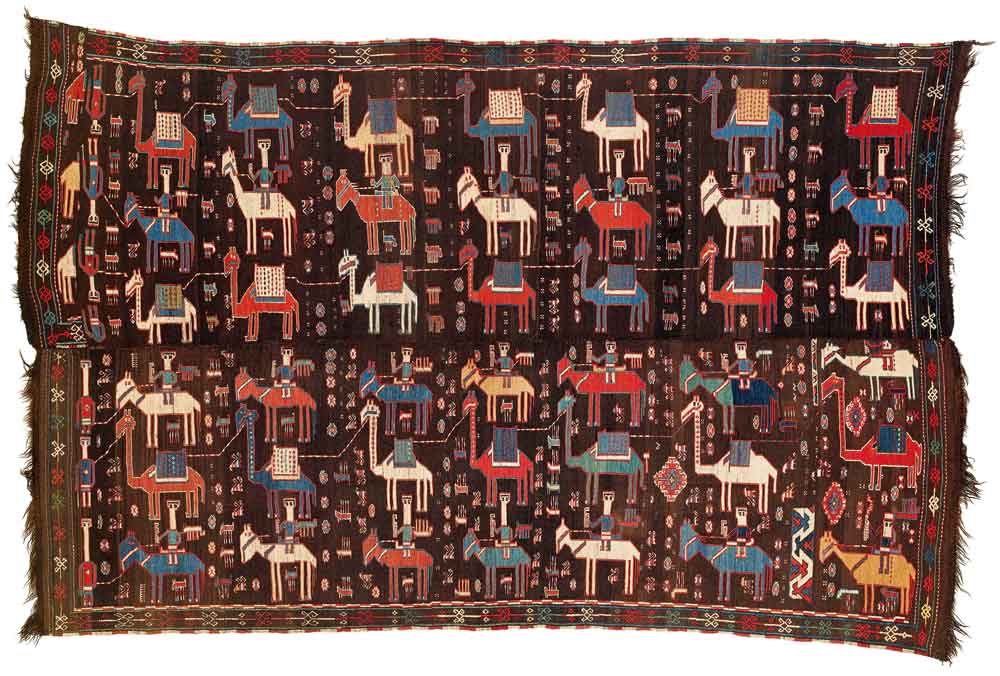

Lot 28. Caucasian Shadda, South Caucasus, Azerbaijan. 252 x 160 cm. 1st half 19th century. Estimate €20,000 – 25,000

There is an impressive array of antlers in his wine cellar, but he is eager to explain: ‘That might look like a lot of trophies but I have been hunting for 45 years. It is just one stag a year.’ I am not a hunter myself but these look to me like some quite significant animals. I sense a personality trait here. Unlike the houses of the Bavarian aristocracy of the 19th century – where even the tiniest yearling antler is displayed in the entrance hall – Ignazio keeps his in the wine cellar where one might sit with friends tasting wine and sharing some bread.

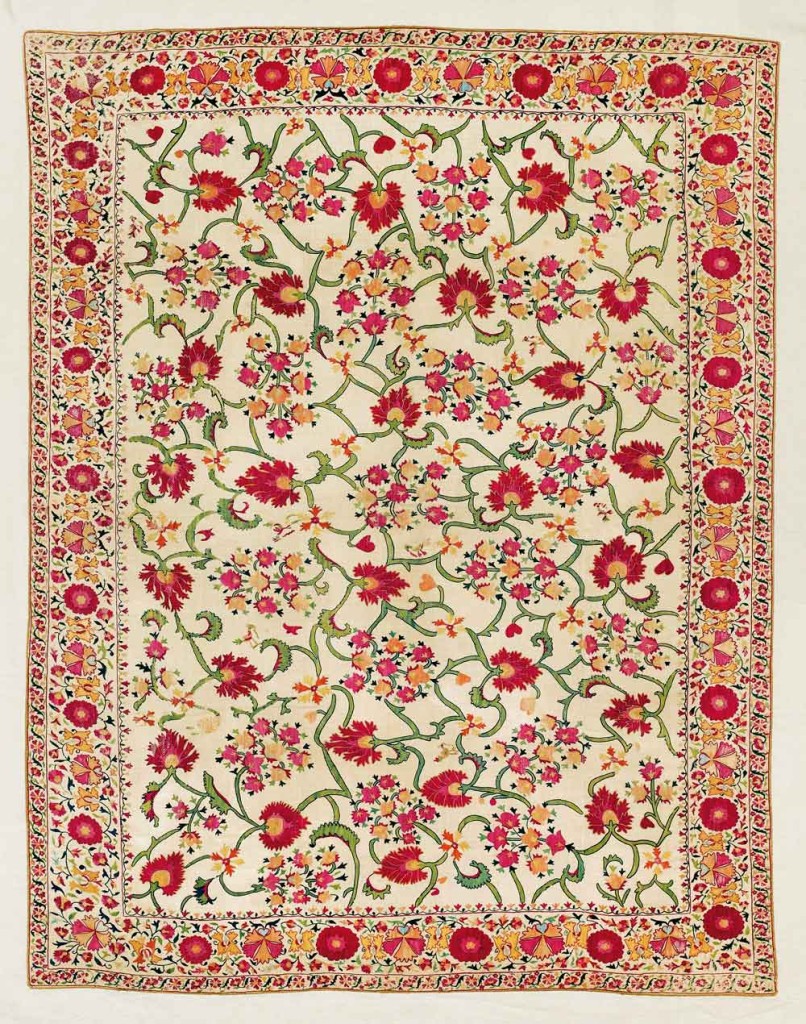

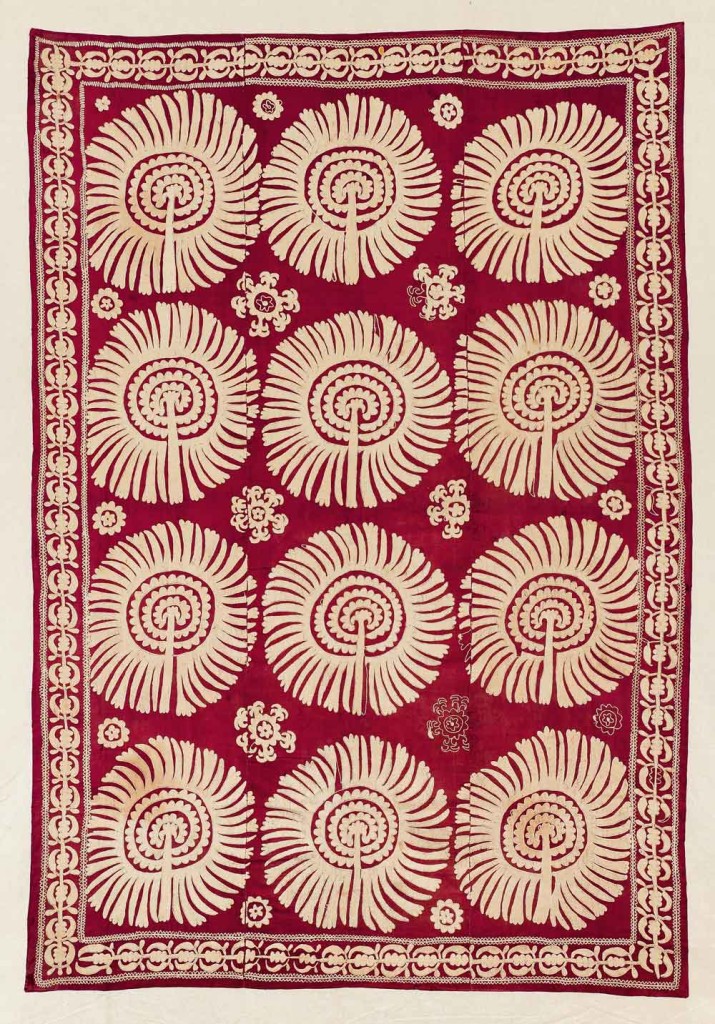

Lot 167. Ura Tube Suzani, Central Asia, North East Uzbekistan. 218 x 165 cm. Early 19th century. Estimate €35,000 – 40,000

I first met Signor Vok in the early 1990s when, thanks to a friendly invitation from Volker and Annette Rautenstengel, I was able to show him my late father’s suzani collection. Many of them had been bought in the Kabul bazar in the 1970s. Piled high in the Rautenstengels’ living room, most were of inferior quality, but Ignazio nevertheless shared his thoughts and insights with me. I had very limited knowledge at the time but I had sensed which one was the best and put it at the bottom of the pile. It was only then that his polite attentiveness wavered and he exclaimed: ‘Ah, this is the quality we want to see!’ And quality we got to see.

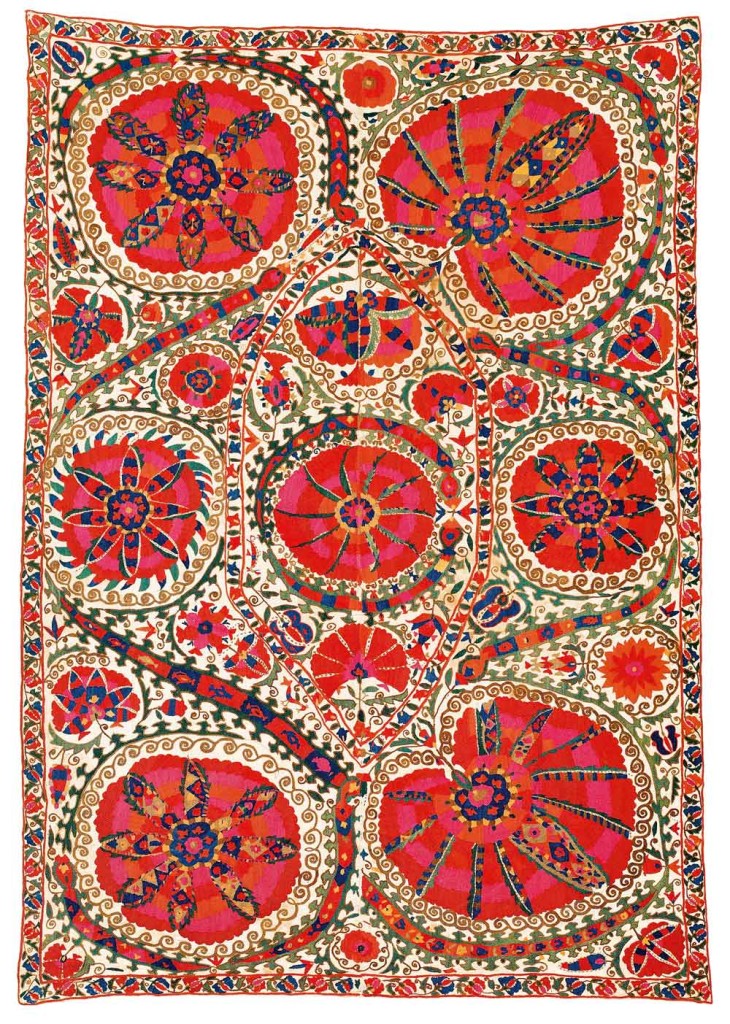

Lot 159. Bukhara Large-medallion suzani, Central Asia, South West Uzbekistan. 252 x 180 cm. Early 19th century. Estimate €40,000 – 45,000

Thanks to the suzani lessons I received at the kind hands of Christian and Dietlinde Erber, I was better able to ‘see’ when Ignazio showed his guests around the Lispida exhibitions, explaining what the pieces meant to him. His enthusiasm for the embroideries had an impact on all of us. The Lispida exhibitions were stunning, as was his elegantly unpretentious hospitality. Signor Vok greeted us in his trademark knickerbockers. For him, having trained as an architect, the granary provided an ideal exhibition space, allowing the textiles to be hung either horizontally or vertically. This was also reflected in the square format of his benchmark suzani catalogues, their covers decorated with a single suzani flower, which was also recreated on a large scale in fruit and flowers on the wall of the stable where we ate. The same flower even adorned the label of his house wine. A Gesamtkunstwerk.

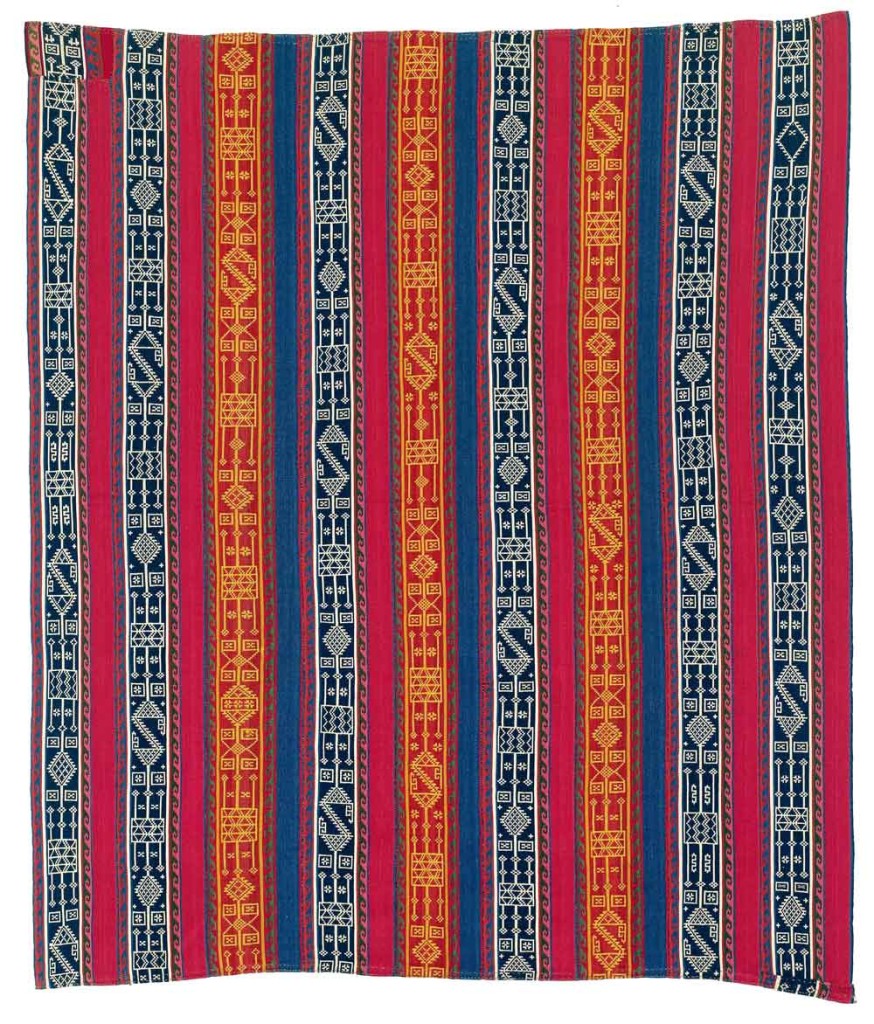

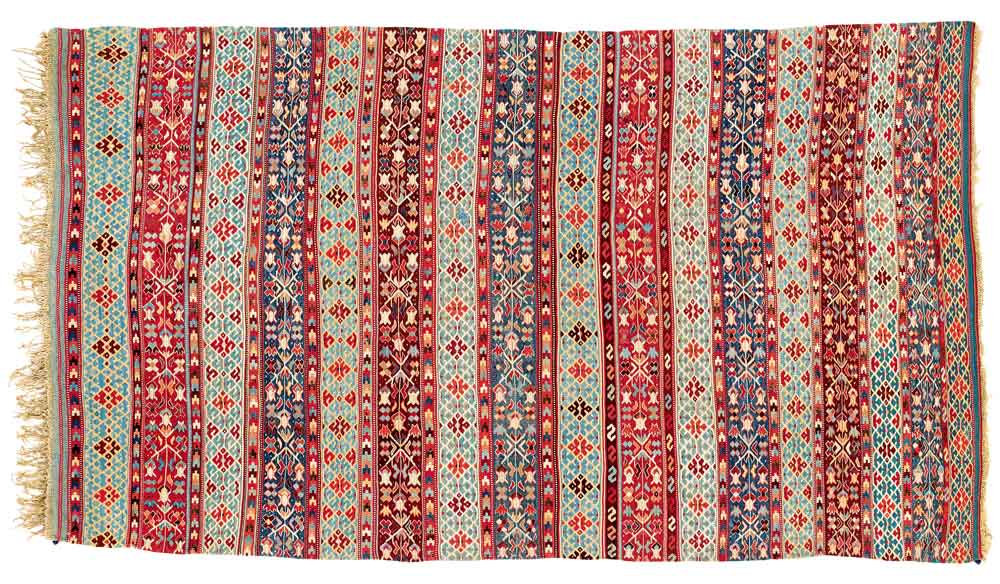

Lot 130. Shahsavan Jajim, South East Caucasus, Moghan region. 212 x 187 cm. Late 19th century. Estimate €3,500 – 4,500

Now we meet without a single suzani in sight and he guides me through a corridor to his office. I notice an eclectic array of artefacts: a wide mix of Asian, European and African art, from contemporary work to antiquities. ‘In my large heart there is space for many passions,’ Ignazio exclaims. I notice that nothing is singled out or highlighted; the art is integrated into his living space. The uneducated eye might perhaps miss the magnitude of the collection. The arrangement seems to be organic, but of course a curating hand is behind it.

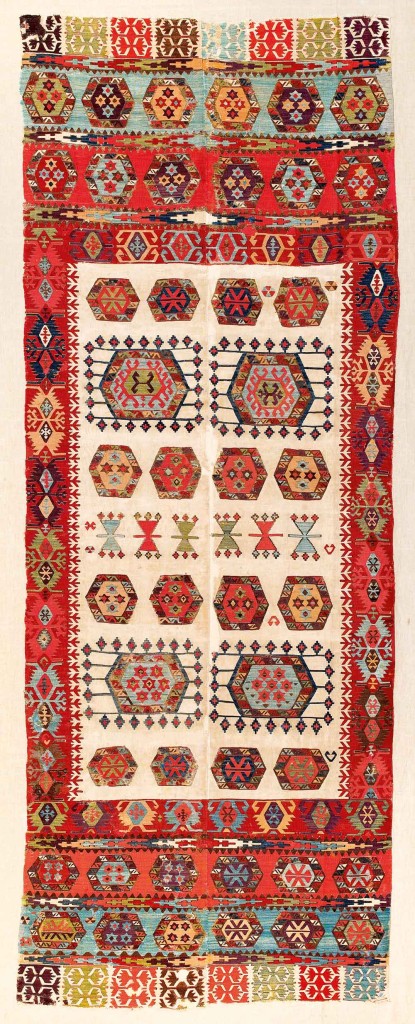

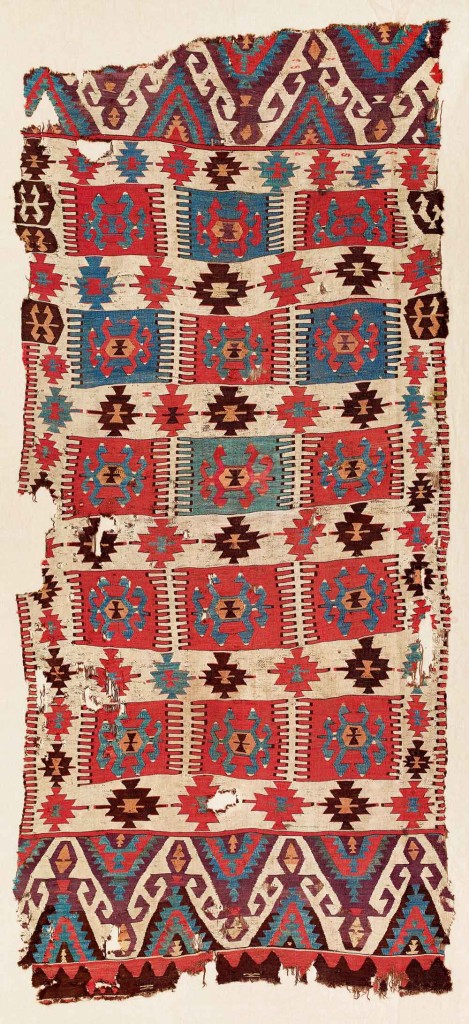

Karapinar Kilim Saf, Lot 93, Central Anatolia, Konya region. 253 x 139 cm. 18th century. Estimate €12,000 – 15,000

Some sculptures are turned around, their backs toward us. ‘Look at these wonderful drapes of the dress.’ He points me towards an elegant bronze. ‘This is to be seen from all angles. Not made for a niche.’ He fondly strokes the backside of an Aphrodite he bought in the 1960s from the antiquarian Julius Böhler in Munich. I see a large modern Japanese calligraphic painting casually leaning against a wall. He explains that it is abstract calligraphy and does not represent real letters. He shows me the different techniques used by the same artist in different paintings. This slightly contradicts the claim he made in his textile books that he has not much knowledge or interest in technical detail or the ethnographic background of the pieces he has collected. Over the course of the day I notice on several occasions that he knows much more about these things than he admitted in print. One must understand that he wants to emphasise the importance of the first sensual approach to art, rather than a purely academic one, but I am sure he would agree that some background knowledge about art is as important as a proper tool for a craftsman.

As we sit down it transpires that ‘Il Architetto’ is very well prepared. He presents me with an organised pile of documents that contains detailed information about his life and collecting. Extensively annotated articles, with comments heavily edited and underlined in different colours, and notes in his trademark abstract but slightly shaky handwriting in his favourite colour red. I feel unprepared and amateurish with my handful of silly questions scribbled on my daughter’s notepad. For a moment I sense something else: there is now a barrier of documents between us. What was a personal and relaxed conversation has become serious. I become worried that this discussion might get tougher than I had anticipated. What comes to mind is the foreword of Vok’s catalogues where he states that his persona can be seen in his collections. Am I only allowed to see him through his documents? It transpires my worries are unfounded: as we work through the papers, his forthcoming, honest and gentle persona lets me ask my questions and answers them in the most generous way.

Lot 106. Aksaray kilim, central Anatolia, circa 1800. 1.42 x 3.91 m (4′ 8″ x 12′ 10″). Estimate €8,000 – 10,000

In the Vok Anatolian kilim book there is a remark about the first sighting of a Pirot kilim in the staircase of Julius Böhler’s Gallery in Munich in 1962, where he was with his father who wanted to buy a painting. So I wondered whether his father was also a collector. Not really: his parents commissioned Art Deco furniture from well-known architects when they settled down in Ljubljana in the mid-1930s. Ignazio, born 1938, grew up in a modern bourgeois household, with paintings by contemporary Slovenian artists on the walls. After the war his father fled from the communists, over the mountains to Italy, with just a trench coat (which Ignazio still has) and a handful of gold coins. He settled in Meran in the southern Tyrol, and slowly started to decorate his new house from scratch. Business trips took him to Germany, particularly to Munich, where he frequented the galleries and antique fairs, and where his son, Ignazio, studied architecture. Munich University is just across the road from the Alte Pinakothek, where young Ignazio spent his lunch breaks and educated his eye on Old Master paintings. Driven by endless curiosity and ambition he studied everything he could lay his eyes upon, including reading a Duden (the German equivalent of the OED) from cover to cover in the bathroom to improve his German. Father Vok soon noticed that the conversations his son had with the antique dealers showed true insight, knowledge and taste. From this there grew a respect from the more experienced dealers toward a man in his mid-20s. So Ignazio became instrumental in his father’s art and antiques purchases, and sometimes he was allowed to buy something for himself like the Aphrodite.

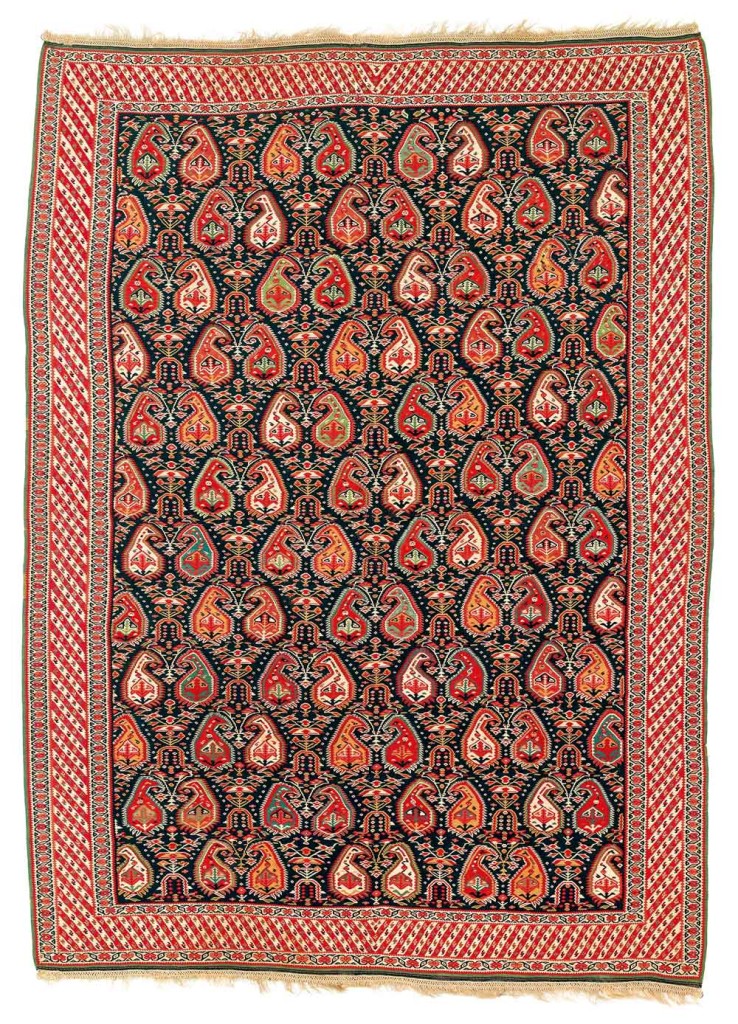

Lot 169. The Jacoby Sehna kilim, North West Persia, Kurdistan. 180 x 130 cm. Mid 19th century. Estimate: €24,000 – 28,000

Vok describes himself as one of the last ‘Habsburgers’ – a person born in Ljubljana/Laibach in today’s Slovenia, but living in the spirit of the time when parts of northern Italy and Slovenia were part of the Austrian Empire, a multilingual, multicultural society under the protection of the Habsburg crown. Studying after the war he found himself considered ‘a friendly Yugoslavian’ by his German classmates, ‘a Slovenian with a bit of Italian’ by his Austrian friends, ‘an Austrian with a bit of Slovenian’ by his Italian mates, and ‘anyone but us’ by the Slovenians. So maybe it is not surprising that he educated himself and relied little on others. Someone growing up with several languages within different cultures, even though all European, might be in part predestined to search for beauty in very different cultures, materials and epochs; finding his voice in the Esperanto of the educated man, the language of art.

Lot: 89. Ferghana Suzani, Central Asia, North East Uzbekistan. 252 x 175 cm. Ca. 1900. Estimate: €3,700 – 4,500

From Ignazio’s catalogues we have learned much about his passion and approach to collecting. His advice to the novice is to trust your instincts and go with your heart, but also to evaluate carefully, take your time and, characteristically, ‘don’t listen too much to others’. I know how often I have opened an auction catalogue and thought ‘Oh, that is great’ only to be less excited the second time, while another piece might grow on you. However, we are all animals of the eye, so a new image will always be attractive. He remembers every image well, knows all the comparable examples in books and museums, but admits not being so well versed in what he has been told or has read. The autodidact shines through, the independent spirit and the hidden artist underneath. He would probably have too much respect for ‘real’ artists to agree that there is something about a great collection which comes close to be a piece of art itself. A good collection is much more than the sum of its parts, a form of conceptual art, ephemeral in this case as the collector/artist has decided to disperse it. Every good collection is deeply personal and Vok wants us to see him through his diverse collections. It was enlightening to re-read the brief condensed introductions to his catalogues. His open-mindedness to quality in all aspects requires both a trained eye and a total lack of prejudice.

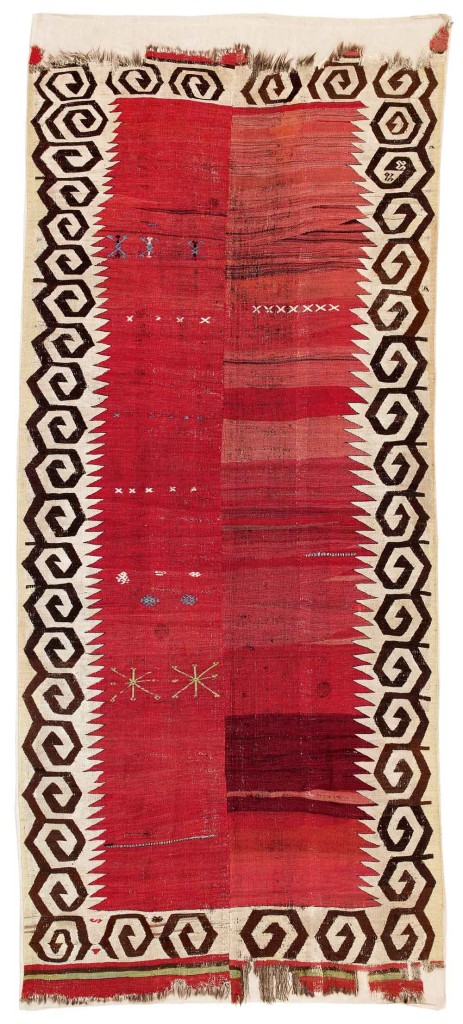

Lot 144. Mut-Ermenek Kilim, southern Central Anatolia, 370 x 159 cm, 17th – 18th century Estimate €30,000 – 35,000

I ask how he felt in the aftermath of the first Rippon Boswell auction. He admits that he had some mixed feelings, but ‘one can make a virtue of need’. The dispersal of a collection can give the collector another pleasure, a different view and a new approach to the works. Suddenly the monetary value becomes important and other people with different tastes have to judge the quality. The auction catalogue texts will be very different from his exhibition ones. To him it gives younger collectors a chance to get pieces in a market that is otherwise not overflowing with new material. Decisions have to be made about pricing and organising the works within the sale, and last but not least there is the pleasure of seeing them hang in different settings and lights.

Lot: 110. Ottoman Kilim, West Anatolia, Manisa province. 265 x 152 cm. 18th century. Estimate: €9,000 – 12,000€

But Ignazio wouldn’t be himself if he hadn’t allowed himself a little treat: having long admired pieces of antiquity in museums, he used the proceeds of the first textile auction to buy himself the stone head of a Greek hero. He cites from a friend’s letter, which she wrote to him after the auction. It contained the last line from Hermann Hesse’s poem ‘Steps’: ‘Wohlan den Herz, nimmt Abschied und gesunde.’ (Courage my heart, take leave and fare thee well.’)

A winter evening sun shines golden through an arched window illuminating the perfect veneer of the Art Deco credenza his father had commissioned from the architect Tautscher. On it there is a pair of bold bronze horses from Renaissance Tuscany. On one side each proudly shows a long flowing mane, and on the other an opulent saddle cloth. As the sun sets, warm honey yellow highlights shine within the deep bronze of their bodies, and the arched window casts a gate-like shadow on the wall within which the shadows of the horse seem to play. ‘I have never really seen them in this light’, says the ever attentive connoisseur.

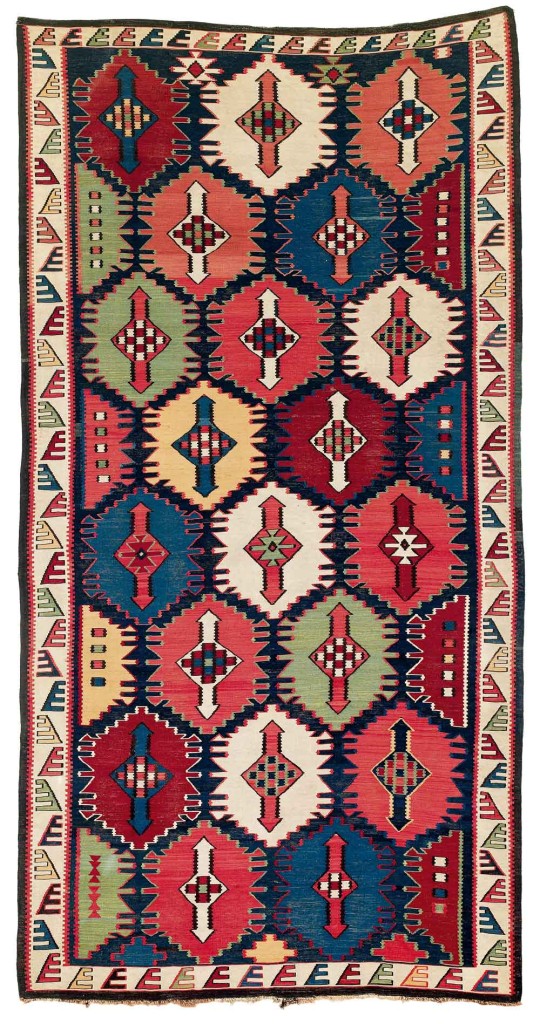

Lot: 119. Konya Kilim, Central Anatolia. 335 x 145 cm. Ca 1800 or earlier. Estimate: €20,000.00 – 24,000.00

This article appeared in HALI 186. To subscribe, visit the HALI Shop.

Comments [0] Sign in to comment