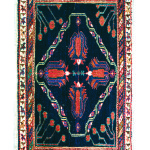

Anatomy of an Object: Afshar ‘Tulip’ Rug

Afshar masnad (small-format audience rug), Sirjan region, south Persia, early 19th century or before. 0.99 x 1.12 m (3′ 3″ x 3′ 8″). Warp: undyed cotton, semidepressed; Weft; undyed wool, 2 shoots; Pile; wool, symmetric knots, ca. 1,600/dm2 (100/in2). Published: Parviz Tanavoli, Afshar, Tehran, 2010, pl.13, pp.13, 73. John Corwin Collection, California

This small Afshar rug, dissected here by Thomas Cole, was one of the loveliest Corwin Collection pieces to be offered for sale in San Francisco by Peter Pap in 2017.

The Afshar were a tribal, mostly tent-dwelling people at the time this rug was woven in the early 19th century. The sophisticated urban influenced drawing of the ‘tulip’ lattice design is distinctively Afshar in its execution, if not in origin—a classical prototype is found in Persian garden and other carpets from the 16th to 18th centuries. According to Parviz Tanavoli, the Afshar have made ‘more carpets with garden motifs than any other tribe in Iran’ (Afshar—Tribal Weaves from Southeast Iran, 2010, p. 40).

The ‘tulip motifs’ at the centre of the field, composed of confronting pairs of palmettes, are rather grand, while the two at either side are only slightly smaller. The rug itself, though, is a small format with an extremely large-scale design—a distinctive quality associated with 18th-century weaving. It would be considered large for a rug twice the size. Although Tanavoli dates it no later than the early 19th century, it may well be a generation or two older.

The elegance of palette and design stand in sharp contrast with later examples of the design type—the expansive, liquid indigo blue field is atypical, accentuated by dramatic and very beautiful abrash. The abrupt unplanned colour changes create an illusion of flowers floating on a still pool of water, a high level of artistry. Seen as a garden design, the diamond lattice of meandering white lines may suggest channels with running water carrying floating vegetation or smaller flowers, perhaps flower petals? It may also be a variant of the patterns associated with the typically simple border systems of many Afshar rugs.

In this early example, however, the primary border has a distinctly different ‘feel’. As the eye relaxes, characteristics of a classic Turkmen minor border emerge with the diagonally crossed lines dividing it into three-dimensional compartments with flower heads interspersed. The Turkmen prototype, though, contains no figurative motifs. Flanked here by simple minor borders that on first glance appear to be a ‘dotted line’, the meandering vine is woven in a subtly different shade of red. Without an outline, the vine recedes, contrasting only slightly to the ground colour on which it appears, an aesthetic of older Central Asian rugs.

The weave is what one would expect in a tribal rug from South Persia, with no suggestion of urban production. The spin of the wool pile varies with the darkest blue applied to what appear to be thicker (or more loosely spun?) strands of wool, while other shades appear to be a finer, more tightly-spun fibre. The combination of unevenly packed wool wefts with finely-spun bleached cotton warps may suggest that cotton was considered prestigious as an item of trade, while the eccentricities indicate a tribal rather than workshop origin.

A number of Afshar rugs of this size, known as masnad, have exceptional craftsmanship and great artistic beauty and are thought to have fulfilled a special function. Tanavoli (p.36) points to the significance of the format, used by the Kermani elite as audience rugs upon which a khan could place his own seat atop a larger, even grander, rug appropriate to his status. Similar sized rugs were also reserved for guests of stature and/or special occasions, a tradition practised throughout Central Asia.

Afshar ‘tulip’ rug

4 images

Learn more about the design elements of this Afshar ‘tulip’ rug.

- The rug is symmetrically knotted with partly depressed cotton warps. The wefts, described by Parviz Tanavoli as ‘possibly camel’, are very soft shoots of fine wool fibre, unevenly spun and loosely packed. If it is camel, it is different to the camelid fibres seen in tribal rugs from adjacent areas.

- The so-called ‘tulips’ at the centre of the field are composed of confronting pairs of palmette designs contained within a diamond lattice structure. Large-scale, each unit measures 43 x 46 cm (17″ x 18″), while those at either side are only slightly smaller.

- At top and bottom of the field, small plots of naturalistically-rendered flowers seem to emerge from water with the illusion of movement—rippling lines as well as surface reflections. The plant forms bring to mind East Asian models with their random use of angular tendrils from which the blossoms have grown, gracefully detailed floral forms reminiscent of Chinese textile art.

- This early 20th-century Afshar bagface from the John Corwin Collection, attributed by Tanavoli to the Aqta’ tribe in Sirjan Province, shows the ‘tulip lattice’ unit compressed, simplified and geometricised. It measures 0.76 x 0.46 m (1′ 6″ x 2′ 6″), is symmetrically knotted, with alternate warps semi depressed. The dark blue ground lacks the depth and variety of tone of the masnad, which is at least a century older.

Comments [0] Sign in to comment