Flora Islamica. Plant Motifs in the Art of Islam in Copenhagen

The David Collection, Copenhagen, focuses on flowers with a new special exhibition that illustrates the overwhelming visual importance of plant motifs for art in the world of Islam, from March 22 – October 27, 2013.

For over a millenium, plant motifs in the form of vines, leaves, flowers, fruits, and trees were among those most frequently used in the art of the Islamic world. Many of these works were created in the hot, barren regions of the Middle East, and the lush Paradise as described in the Qur’an would have appealed to the Muslim artists. Traditionally, living creatures and humans are very rarely depicted in Islamic art, primarily for religious reasons. The key metaphysical justification is that Islamic art depicts the inner reality of a phenomena, so the prohibition is related to the non-personification of reality. The inner reality of specific patterns of art made by Islamic artists signifies uniformity, unity and beauty of nature.

The great diversity of the plant kingdom provided a neutral subject that could be artistically stylised and made abstract. The exhibition reveals motifs of plants and ornamentation depicted on everything, from the most mundane objects such as ceramics to luxury items such as manuscripts, textiles and weapons. One vegetal ornament, above all, has almost become synonymous with Islamic art: the arabesque.

‘Flora islamica – Plant Motifs in the Art of Islam‘ presents 66 pieces from the museum’s Islamic Collection and one Persian work of art each from Rosenborg Castle and Designmuseum Danmark. The exhibition is organized as follows: The Heavenly and the Earthly Garden, Inspiration from Antiquity, Inspiration from China, Abstraction, The Arabesque, Fantasy, Naturalism, Plants as a Symbol, Flowers of the Gunpowder.

This incredibly well preserved and vibrant silk carpet was first mentioned in Rosenborg Castle’s archives in 1718, but may have come to Denmark in around 1666 together with the famous coronation carpet that is also found at Rosenborg today. Experts have described the carpet as a Polonaise without a metal ground made in the court workshops in Esfahan, although the pattern may resemble the less costly Esfahan carpets of wool. The design, symmetrical over two axes, is dominated by blue arabesques holding feather-like serrated leaves, smaller flowers, and ten large composite flowers. These last elements are various fantasies on Chinese models combined with leaves, smaller flowers, and something that resembles pomegranates.

The beveled style is three-dimensional almost by definition, but is also found in two-dimensional versions, as on this unusual bowl decorated in luster.

The design consists largely of halfpalmettes, some of which are highly stylized while others are laciniated and slightly more naturalistic. As on arabesques, they grow from or extend one another unnaturally. It is difficult to differentiate between background and pattern, however, on closer inspection, it becomes clear that the golden luster decoration is what forms the complex palmette motif.

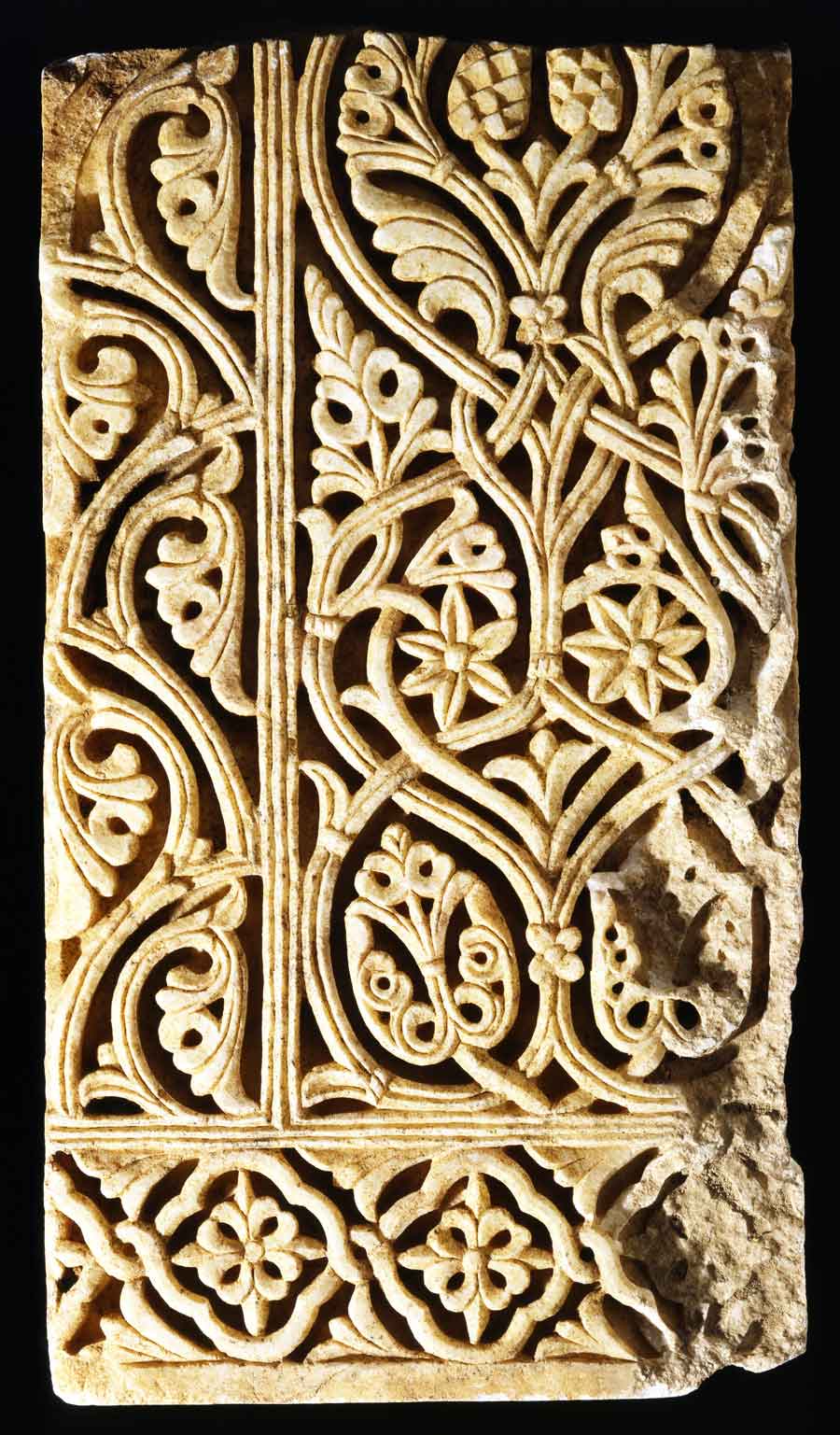

Marble relief, Spain, Cordoba, second half of 10th century

The Spanish Umayyad dynasty, descended from the Syrian Umayyad caliphs, remained truer to the styles of Antiquity than the Abbasid caliphs in Baghdad. The Spanish Umayyads reached their zenith in the 10th century, when Cordoba and the palace city of Madinat al-Zahra were decorated magnificently. Innumerable capitals and reliefs like this one were created in a style that clearly originated in Antiquity yet heralded a new idiom. The tendency was the same throughout the Islamic world. The acanthus and vines of Antiquity were stylized and denaturalized, and symmetry triumphed at the expense of natural growth. This relief shows an incipient arabesque that in time would be further developed.

Islamic artists adopted motifs from Antiquity that had previously had a more or less pronounced symbolic significance that was lost in the new cultural context. Examples are sphinxes, harpies, griffins, sun symbols, and the Tree of Life. This last motif, the Tree of Life, is an ancient symbol dating back several millennia before the Christian era, and whose significance is quite vague. It is the tree of the gods that links heaven and earth. It is often flanked by two or more animals or mythical creatures and became a well-established motif in textiles with medallion patterns. There is no evidence that the motif has any specific significance in Islamic art, where it should be viewed as a decorative relic.

The designs of large-patterned Ottoman silks from the 16th century are among the most sublime woven anywhere. They were made in Bursa and Istanbul, and their patterns were often designed by the artists in the court studio (nakkaşhane). The most impressive group of these fabrics can in fact be found in the Topkapi Palace’s collection of the Ottoman sultans’ caftans.

Rows of stylized tulips form the pattern. The tulips have six petals: the outermost two are golden and blue with Chinese cloud ornaments, and the four innermost are silver and blue with a scale pattern. A seven-headed stamen and an odd stalk further denaturalize the motif. The use of precious metals for these textiles resulted in several bans on weaving them.

A common motif in poetry through-out the Islamic world, one that was also very popular in visual art from the 17th to the 19th century, is the rose and the nightingale – gol o bolbol. The rose stands for sublime feminine beauty; the nightingale symbolizes the male admirer. Together they are a symbol of love and at times a metaphor of the impossible or unattainable love. The Great Mughal Akbar wrote the following verse: “It is not dewdrops that fall on the rose / They are only tears from the nightingales.” The rendition of the bashful nightingale and the luxuriant flora with roses, branches of common St. John’s wort, and other plants both come from a time when naturalistic models from Europe influenced Persian painting.

The Great Mughal Jahangir (r. 1605-1627) was captivated by nature, both animals and plants, and depictions of them and court portraits achieved a high degree of naturalism during his reign. This trend continued under his son Shah Jahan (r. 1628-1657), from whose early reign the border of this album leaf probably dates, though the painting of King David is from Jahangir’s reign. Jahangir is said to have become interested in flowers during a trip to Kashmir in 1620, but the European engravings and paintings that had already arrived at the Delhi court during the reign of his father, Akbar

(r. 1556-1605), were also an important factor. David was copied directly from a Flemish engraving, and the flowers were influenced by contemporary European botanical works, florilegia.

This delicately painted composition features three plants with a number of similar, though highly imaginative, corollas that in some cases seem to be made up of leaves rather than petals. On the two largest, the petals enclose a pomegranate-like body. The painting was executed in gold and silver on paper tinted brown. Scattered among the plants are three cocks and a hen whose tail feathers could be viewed as part of the already fanciful flowers. The painting is most closely related to the type made as margin decorations in the most luxurious manuscripts produced under Shah Tahmasp (r. 1524-1576). Based on other works, it can be ascribed to Sultan Muhammad, one of the Safavid shah’s most trusted and outstanding artists.

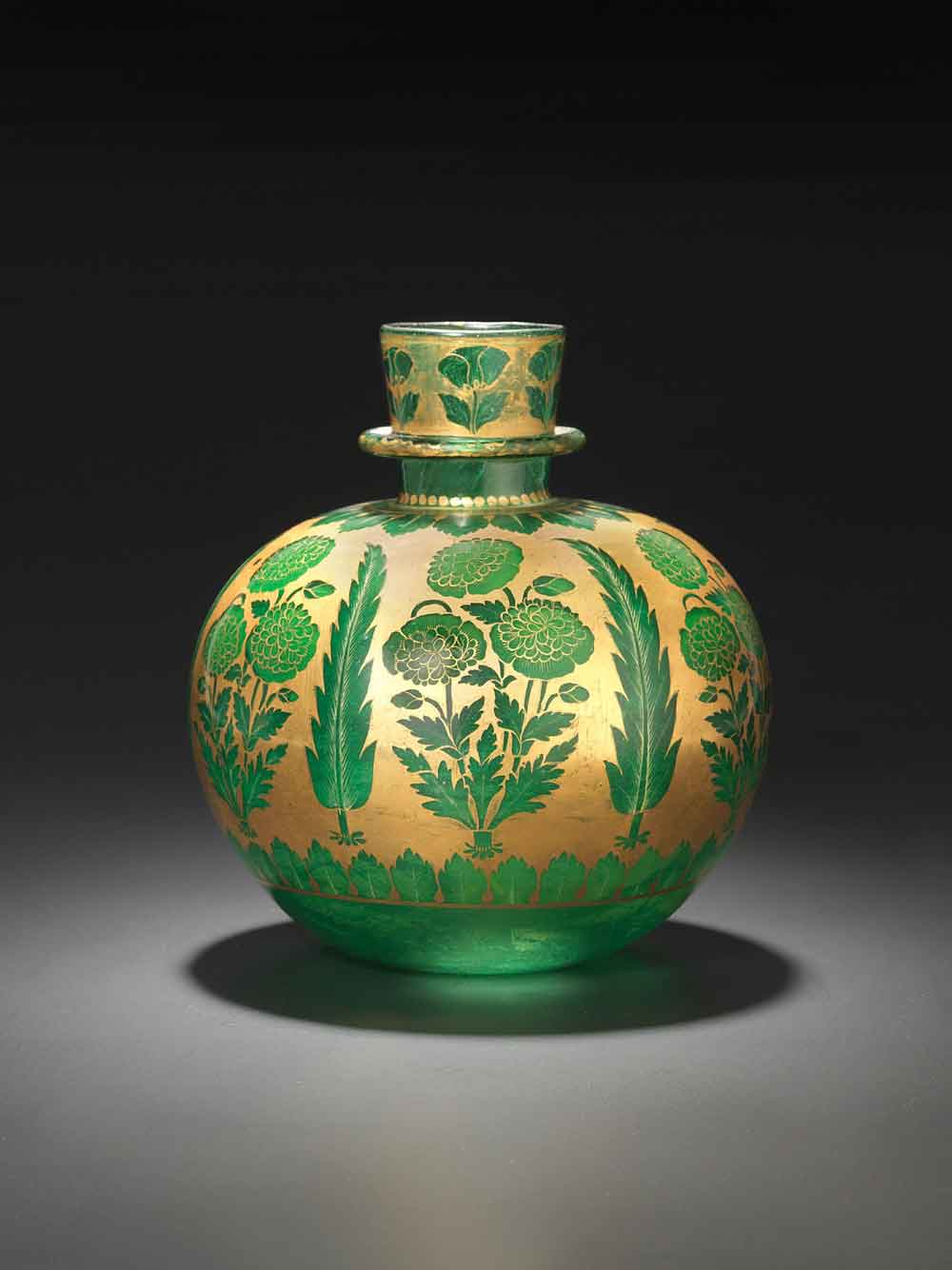

The brilliant emerald-green glass of this water pipe is the ground color for the six poppies and six cypresses painted in reserve on a golden ground. Details are painted in gold, and inside is a layer of enamel paint to create depth in the composition. The asymmetrically arranged poppies of different kinds on the neck seem quite natural, though a little stiff.

Several of the Great Mughals were habitual users of opium, derived from the opium poppy, papaver somniferum. It is no coincidence that the poppy was often found as a decoration on water pipes, which could be used to smoke opium mixed with tobacco.

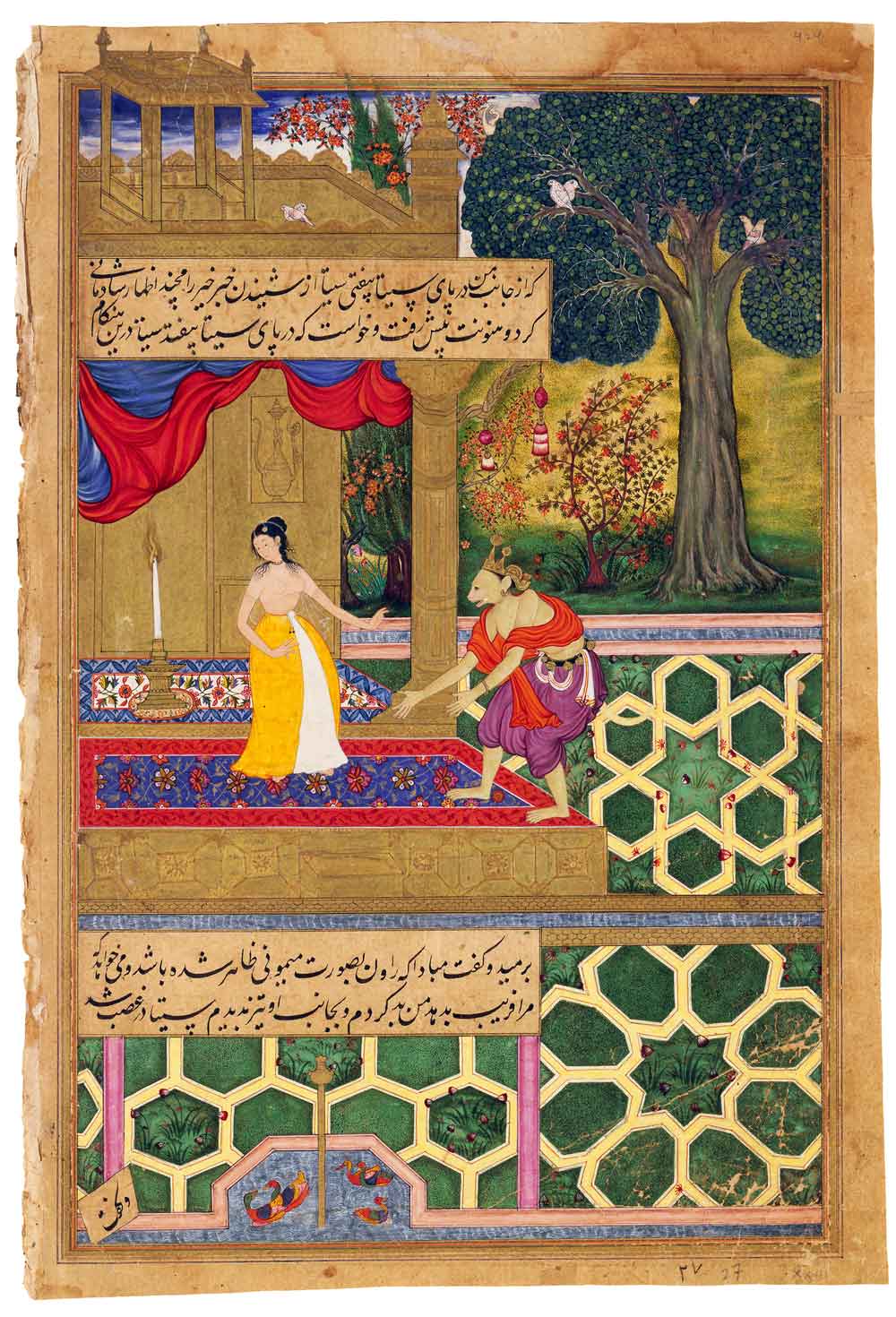

This miniature is from the copy of the Ramayana that the Great Mughal Akbar commissioned for his mother in 1594. Nearly all the Great Mughals were enthusiastic founders of gardens, either at palaces or at mausoleums, like the famous Taj Mahal. Many Mughal gardens were of the Persian charbagh type, divided into four sections by channels, and these sections could be subdivided into innumerable sunken beds with geometrical patterns and hold smaller irrigation channels, fountains, and pavilions. The architecture, as here, was often further decorated with flowers in relief or in inlays. Rugs brought the wealth of flowers from the real garden into the pavilions, and some were even designed as stylized gardens with beds and watercourses.

Innumerable copies of blue and white Chinese export porcelain were made in Iran from the 15th to the 17th century. The quality varied, and only rarely did the results have independent artistic value. This magnificent dish does, its design created by the potter cutting through the intense blue slip down to the white fritware.

While the simple pattern on the rim, consisting of double split leaves joined by a five-petaled flower, shows ties to Islam, the nervously quivering plant in the center is oriented toward China. The plant has four lotus-like flowers, a few simple little leaves, and other more eccentric ones that resemble the jagged cloud ornaments that surround or perhaps emerge from the flowers.

Silk textile with animals and mythical creatures in vine scrolls, Central Asia or Eastern Iran, 13th century

Textiles woven in or near Central Asia have shown the influence of both East and West since ancient times, and this is also true of this vibrant silk. The inscription frieze at the top is based on Arabic, and both the griffins and the lions have a clear Western look. The lively arabesque-like swirling vines in two layers (one red, the other brown) point in both directions, while the heavy, colorful flowerheads are clearly inspired by the Chinese lotus and peony. The frieze is a good example of how calligraphy and vegetal ornamentation were merged into an artistic whole. In contrast to the somewhat older bowls, where letters develop into plants, these end in animal heads of different types.

Comments [0] Sign in to comment