The ubiquitous ikat

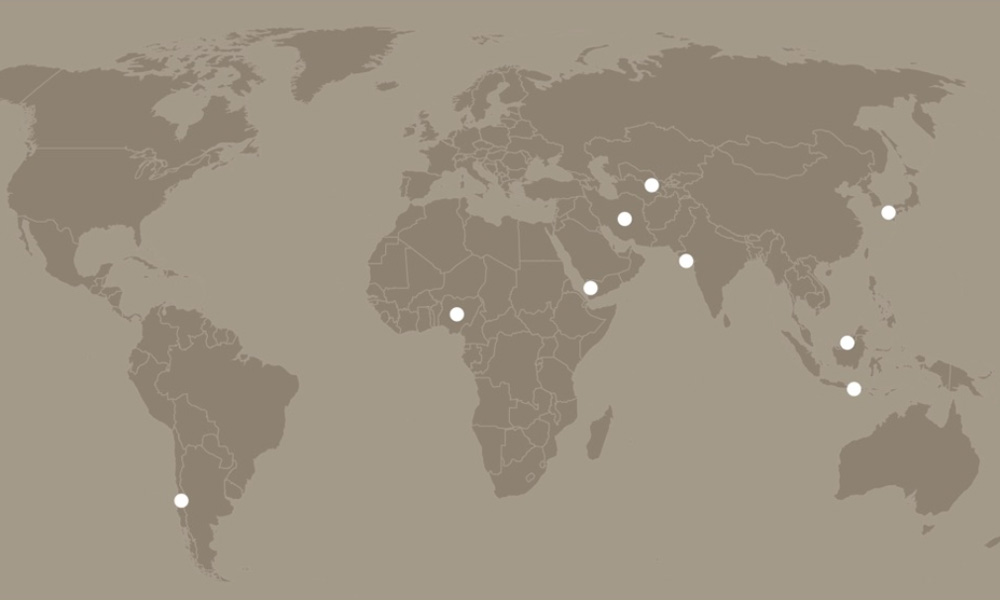

Ikats occur in widely separate geographic regions, including Africa, Europe and the Americas, although the best known and most ancient are the sophisticated weavings from Asia, particularly Central Asia, India, Indonesia and Japan. The term ikat describes both a finished decorative textile and the dyeing technique used in its manufacture. The catch-all word is Malay, and refers to the resist-dye process where the warp and/or weft yarns are dyed before the fabric is woven. Thus, the final pattern is literally dyed onto the individual silk, cotton or wool threads, a complex, highly-skilled and time-consuming process, particularly when many colours are to be used. The meticulously-planned patterns may be carried on the warps or the wefts, occasionally on both. Groups of threads are bundled together and those sections which are not to be dyed at each consecutive stage are tightly bound with an impermeable material to form areas of resist. Due to the difficulty in tying the resists for each area along precisely the same lines, colour seepage at the edges of the bindings, and the subsequent alignment of the unbound threads on the loom, there is a certain merging of adjacent colours, which produces the slightly blurred effect so characteristic of these weavings.

IRAN Pardeh, door curtain (detail), Central Persia, 19th century. Silk, warpfaced ikat velvet. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. J. H. Wade, 1916.1388. During the Qajar period, colourful warp-ikat silk and silk velvet fabrics, used for door curtains (pardeh) and other furnishings, as well as for tailoring into garments, were woven in commercial workshops in the cities of Yazd and Kashan. The cypress trees are traditional Persian motifs of great elegance and beauty.

CHILE Mapuche chief’s poncho (detail), southern Chile, early 20th century. Wool, warp ikat, indigo-dyed. Andrés Moraga Textile Art, California. In the western hemisphere, the striking blue and white geometric forms created in warp-ikat technique on the chief’s woollen ponchos (trarikanmakun) of the Mapuche tribe from southern Chile proclaimed the identity and status of the wearer.

BALI Geringsing Wayang sacred textile (detail), Tenganan, Bali, Indonesia, 19th century. Cotton, doubleikat, natural dyes. Private collection, California. This intricate double-ikat (warp and weft) cloth was woven on a simple backstrap loom into a fabric in which both warp and weft threads are visible. Intended for wear as a ritual garment, the mandala forms are recognised by the Hindu weavers of Tenganan as small house temples and sources of holy water, and are potent reminders of the profound Indian influence in southeast Asian textile art.

UZBEKISTAN Bukhara Munisak robe (detail), Central Asia, 3rd quarter 19th century. Silk, seven-colour warpikat velvet (bakhmal) on cotton warps. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Promised Gift of David and Elizabeth Reisbord, PG.2018.10.1. Called abr in Central Asia, ikats, whether all-silk (atlas) or half-silk (adras), are reliably the world’s most brilliantly colourful textiles. Here the warp-ikat technique has been combined with the complex velvet weaving process to produce lengths of fabric for tailoring into the colourful robes worn by both men and women in the Emirate of Bukhara.

YEMEN Tiraz fragment (detail), Sana’a, Yemen, Zaydi Imam period, ca. 960–980 ce. Cotton, warpikat with painted inscription in gold leaf. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund, 1950.353. Among the oldest of all ikattechnique textiles are Yemeni cotton warp-ikat tiraz with patterns in variegated shades of indigo blue, tan and ivory and embellished with painted or embroidered pious inscriptions, which were made in workshops in the capital, Sana’a, during the late 9th and 10th centuries. Most surviving pieces of Yemeni ikat were recovered from the ancient middens at Fostat in Egypt. The warpikat technique is called ‘a sb in Arabic.

GUJARAT Elephant patola ceremonial cloth (detail), western India, 18th century. Silk, warp- and weft-ikat. Heidi and Helmut Neumann Collection, Switzerland. There are two primary design types of Gujarati fin e silk double-ikat patola, with the design carried on both warp and weft threads: the majority are patterned with abstracted floral motifs, while those examples decorated with caparisoned elephants, as here, are altogether rarer. The oldest surviving examples are seldom found in India, where they were used as clothing and were worn out, but rather in the islands of Indonesia, where they were imported for use in ceremonies and thus preserved as sacred heirlooms.

NIGERIA Igarra woman’s wrapper cloth (detail), central Nigeria, early to mid 20th century. Handspun cotton, warp-ikat. Karun Thakar Collection. This fine ikat- patterned woman’s wrapper cloth from the small town of Igarra, near the confluence in the Niger and Benue Rivers in central Nigeria, is woven from hand-spun indigo-dyed cotton. White ikat patterns are the rarest on Igarra cloths, with yellow most typical. Igarra was one of the few places in Nigeria where ikat dyeing was practised by women weavers, and smaller women’s wrappers are far more frequently seen than the larger cloths worn by men.

BORNEO Iban Dayak Pua Kumbu ritual cloth (detail), Mujong River, Sarawak, 16th-17th century. Cotton, warp-ikat, natural dyes. Heribert Amann Collection. This warpikat ritual cloth with the complex trophy head (buah rang jukah) pattern, which has been remarkably wellpreserved in Borneo’s humid rainforest conditions, has been C-14 dated to between 1550 and 1640 ce, making it one of the earliest known textiles of its kind.

GUJARAT Mashru textile (detail), western India, late 19th century. Silk, warp-ikat stripes alternating with brocaded stripes on cotton wefts. Sarabhai Foundation – Calico Museum of Textiles, Ahmedabad, 872. Woven in silk and cotton, this vertically striped fabric is known as mashru, literally ‘that which is in accordance with Sharia’, the Muslim holy law which disapproves of garments such as pajama made of silk only. While outwardly opulent, only the more conservative cotton side of the mashru would touch the skin of the devout. Alternating with the red warp-ikat bands with white chevrons are patterned bands in a brocading technique, which contrasts the dark silk warps with the visible white cotton wefts.

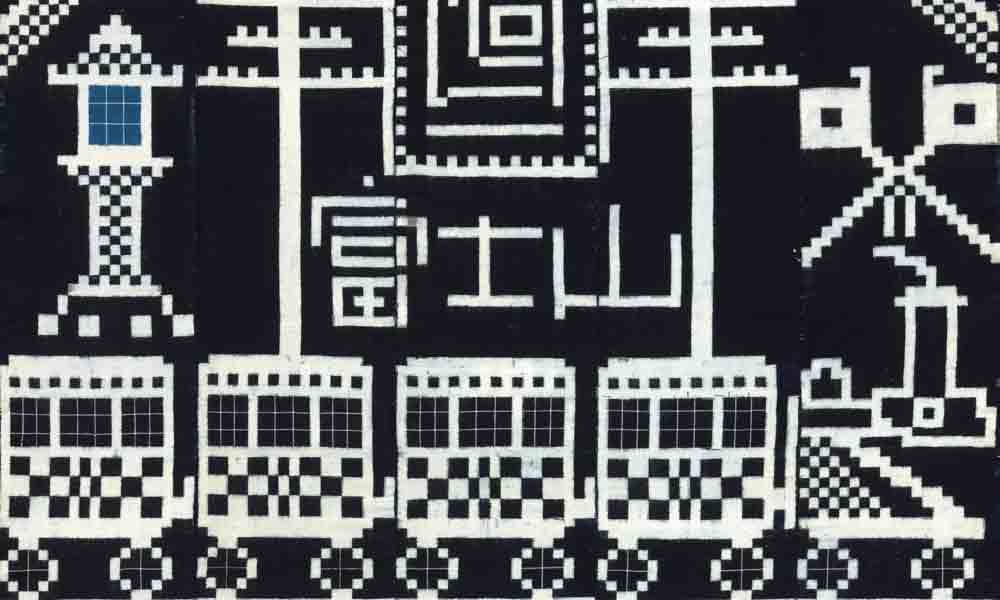

JAPAN Kurume-gasuri futonji (detail), Kurume, Fukuoka Prefecture, Kyushu, Meiji period, ca. 1900. Cotton; indigo dye, double-ikat (tate-yoko gasuri). Minneapolis Institute of Art, The John R. Van Derlip Fund and the Mary Griggs Burke Endowment Fund. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Japanese city of Kurume was famous for its pictorial double-ikats, known as kurume-gasuri, which often had script conveying nationalistic messages. In this futon cover the design includes a steam locomotive and carriages on an elevated track, with telegraph poles and Mount Fuji in the background. Under the tracks an inscription identifies the Naka River, which runs from Saitama to Tokyo. Kurume-gasuri became prized trousseau items for wealthy brides, and in 1957 they were designated ‘Important Intangible Cultural Property’.

Comments [0] Sign in to comment